Each academic year, David Nirenberg, the Institute for Advanced Study’s Director and Leon Levy Professor, welcomes incoming scholars with remarks delivered in Wolfensohn Hall.

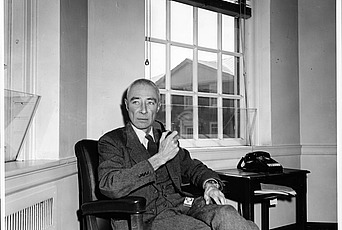

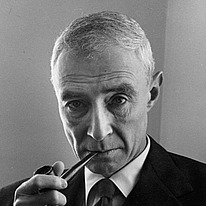

Nirenberg’s remarks to the 2025–26 class, given in full below, drew inspiration from a wide range of thinkers, from anthropologist Victor Turner (Member in the School of Social Science, 1975–76) and art historian Erwin Panofsky (Professor in the School of Historical Studies, 1935–68) to the Institute’s third Director (1947–66), J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Nirenberg described the Institute’s unique role as a “space of thought and a time of mind”—a place set apart from many of the demands of academic life, dedicated wholly to the pursuit of knowledge.

Reflecting on the Institute’s history and the interplay between solitude and community, Nirenberg shared how IAS fosters both deep concentration and unexpected encounters. He recounted legendary collaborations—such as that between John von Neumann (Professor in the School of Mathematics, 1933–55) and Oskar Morgenstern, which gave rise to game theory—and the value of reaching beyond one's intellectual comfort zone. Through stories from the Institute’s past and present, Nirenberg highlighted the importance of dialogue across disciplines, from mathematics and science to history and the arts.

As the Institute’s Members embark on a year of research and discovery, Nirenberg invited them to embrace conversation, challenge assumptions, and find inspiration under the Institute’s “magnificent sky.” His remarks celebrated the fragility and promise of spaces devoted to the freedom of thought, urging every scholar to make the most of their time in this remarkable community.

The remarks are also available to watch on YouTube.

Thank you for joining me for this brief—though perhaps not as brief as some might wish—ceremony of welcome. We are not a university: we have no commencements, no graduations. In fact, for an institution approaching its second century, we have remarkably few ceremonies or rituals, and those we do observe are invariably organized around food—as is this one. The best part, I assure you, is still to come.

Still, many societies use rituals to mark “liminal moments”—what anthropologist Victor Turner, himself a Member here from 1975–76, called “betwixt and between” moments, at the threshold of change. So it seems appropriate to honor, with such a ceremony, our collective entrance into a new year and a new and extraordinary community.

On occasions like this, significant philosophy has sometimes been uttered—John Dewey’s “The Aims of Education” at the University of Chicago, or [Giambattista] Vico’s inaugural lectures at the University of Naples. But neither, as far as I know, were Members or Faculty of the Institute, and I do not pretend to offer philosophy of their caliber. Instead, I wish simply to reflect on what it is we are celebrating. Each of you may have a different answer. From my perspective, we are celebrating our entry—or, for some, our return—into a very peculiar space and temporality: a space of thought, and a time of mind.

We are entering a place whose “spacetime”—I have learned this term from our physicists—is different from the world you come from, in that it is wholly dedicated to the possibilities of thought and discovery, and specifically, to your thought and your discoveries.

It is easy to sense the distinctiveness of this space. We feel it in the absence of teaching and committee obligations, of sports teams, of economic missions or political statements—indeed, of any of the many purposes to which colleges and universities are devoted, save for the single purpose of supporting your exploration of whatever question you wish to pursue. We sense it in the fact that our residences, offices, dining halls, common room, schools, centers, and convening spaces are all designed to hold us together in a community capable of generating both solitude and encounter, and of insulating us from the demands of the outside world.

We sense it, too, in the roughly 600 acres of forest, field, and meadow that replace the purposeful lines and angularities of the everyday world with the fractal leafiness and winding paths so well-suited to peripatetic cogitation. That invitation is deliberate: the early Faculty formed a Committee on the Woods to lay out and blaze trails for their walks. If you ask our archivist, Caitlin Rizzo, she can show you a photo of Paul Dirac, the physicist, with an axe on his shoulder, heading off to blaze those trails. The darkness of the night sky, the boldness of the deer—yes, they are very bold here—the presence of fireflies and foxes, of bluebirds and orioles, even the circling turkey vultures and the occasional bald eagle, all help us feel that the Institute is not quite the world we left, and to which many of us will return.

This peace and this freedom should not be mistaken for purposelessness. Our distinctive space is in the service of a distinctive temporality—a time of mind. The passage of time is perhaps the most familiar and implacable given of our finite existence. But here, we strive to make time at least temporarily unfamiliar. We are here to bend time, as a great pianist bends the tempo of a Bach sarabande, away from the short-term horizons of the everyday world. In so doing, we create possibilities for exploration and discovery that can only arise when we still the rumblings of being long enough to attend to a question leading beyond the immediate horizons of the known. The Institute exists for this reason: to offer you the opportunity to occupy that time of mind, in a community capable of nourishing knowledge at its most difficult.

Nietzsche—again, not a Member, though imagine the lunchtime conversations—once complained that most of the world, when it asks for knowledge, wants “something strange to be reduced to something familiar.” He called this “the error of errors.” Greater discovery, he wrote, lies in becoming aware of our most basic assumptions, so that we can question them and make them strange. You are entering a community that exists to offer you the conditions for that estrangement. Since its founding, the Institute has sought to “assemble thinkers capable, through their talent, proximity, collaboration, conversation, and tolerance of difference, of producing insights and discoveries that could not otherwise have been made.” The commitment has never been to an ideological or disciplinary consensus, but to the constant testing of ideas, so that the unfamiliar may emerge from the known.

You—indeed, we—constitute the community of thinkers for this coming year, waiting to be surprised by the directions your thoughts and dialogues might take you. The Institute rightly prides itself on the fields that have emerged from such dialogues, often across disciplines.

To take one early and famous example: the economist Oskar Morgenstern and John von Neumann met not over tea at the Institute (alcohol was not served at tea) but over drinks at the Nassau Club down the street. Today, the Rubenstein Commons can serve the purpose they sought. That encounter led to their joint authorship of Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Their goal was to create a new science of the psyche, to find laws as logically consistent as those of physics, to predict human behavior. The result was the field of game theory, which today is used to think about everything from nuclear strategy to the matching of friends and partners on Facebook and Tinder, from dynamic pricing models in our economies to the security algorithms that protect them.

Reflecting on the consequences of von Neumann and Morgenstern’s conversations for our world, I urge you to be as adventurous and open as possible in your own dialogues—to reach out beyond your familiar intellectual circles. This is not always easy, even here. Karen Uhlenbeck, long-term Distinguished Visiting Professor, wrote in her report on the special year in Geometric Partial Differential Equations (1997–98) that “while I always hoped for some mixing, the physicists ate at one table and the math people at another. I have no clear idea how to influence this kind of intermingling.” It is not easy, but it is possible.

A mathematician from last year divided his report into three parts: collaboration with mathematicians, with physicists, and with social scientists. Of the latter, he wrote, “I learned immensely from the Social Science seminar and my interactions with scholars whose research interests intersect with mine. Although it’s harder to measure their impact in terms of publications, these seminars, conversations, and relationships will shape my scholarship moving forward.” One of the gifts of our intimate community is that it is possible to “switch tables,” so to speak, and I urge you to take advantage of that—cultivating conversations and encounters that have the power not only to confirm, but to transform our assumptions, and thus our worlds.

Let me offer just one example. What if, instead of encountering the mathematically inclined economist Morgenstern, von Neumann had chanced upon his colleagues and fellow refugees, the art historian Erwin Panofsky and the medieval historian Ernst Kantorowicz, as they chatted under the Institute’s dark sky one February night in 1952, after an evening at the movies? Kantorowicz mused, “Looking at the stars, I feel my own futility.” Panofsky replied, “All I feel is the futility of the stars.” These two were, in their way, debating the same point that Morgenstern and von Neumann had tackled, though from a different perspective.

Immanuel Kant—again, not a Member—famously drew an analogy between the laws that govern galaxies and those that govern humanity: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe—the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.” Kantorowicz was invoking this parallel; Panofsky’s witty retort was a challenge to the idea that our inner lives can be reduced to physical law. I like to imagine what a conversation between von Neumann and Panofsky might have looked like.

For a hint, I turn to an essay von Neumann published in Fortune in 1955, “Can We Survive Technology?” In it, he predicted that changes in weaponry, communications, and climate required the world to develop new political forms and ideals if it wished to avoid “forms of climactic warfare as yet unimagined.” The only recipe for surviving technological change, he concluded, was to rely on human qualities. But what are those qualities, and how can they help us achieve new ideals and forms of life? Such questions are as urgent today as they were in von Neumann and Panofsky’s time. To answer them—or even to ask them in a way commensurate with their difficulty—we need the humanist and the physicist, the social scientist and the mathematician, indeed everyone in this community, to be in dialogue under our starry sky.

This was, in fact, the vision of J. Robert Oppenheimer, our longest-serving director. If you’ve seen the movie, you know Oppenheimer, like von Neumann, was consumed with the consequences for humanity of scientific progress—especially the physics of the atom, whose powers he helped unleash. He championed such progress—supporting von Neumann’s work on the programmable computer, for example—but thought it was not enough. “The safety of a nation or the world,” he believed, “cannot lie wholly or even primarily in its scientific or technical prowess.” It must also attend to ethics, religion, values, political and social organization, feelings, emotions.

Oppenheimer believed that the challenges of the future could only be met by bringing the technological and the human together. He sought to make the Institute a place where these many forms of thought could come into conversation. The list of people he brought here—[Noam] Chomsky, T. S. Eliot, [Jean] Piaget, and many more—is truly extraordinary, including in fields we have never had permanent Faculty.

Such conversations are never easy. They were not easy in the early years, a time of economic collapse, sharp discrimination, technological transformation, rising nationalism, displaced peoples, and the flames of war. Nor are they easy today: in a world of technological change, the reemergence of borders and barriers to the exchange of people and ideas, rekindled nationalism, war, mass migration, and renewed conflict over the nature of universities and research. All these forces threaten to intrude upon what the Institute’s founding Director Abraham Flexner called “this paradise for scholars.” The Institute is not a paradise—it is very much of this earth, dedicated to its study and subject to its vicissitudes. But the Institute is a locus amoenus—a special place, in its space and temporality, and in its constant commitment to engagement and debate over ideas.

You come from many places—some forty countries this year. This diversity was by design and lies at the foundation of our ideals. In its founding document of 1930, the Institute committed itself to remaining open to people of all religions, genders, races, and nationalities—a commitment rare in the 1930s, and just as critical and difficult to uphold today. Oppenheimer, for instance, moved heaven and earth to bring emerging Chinese scholars to the Institute in the 1940s—mathematician S. S. Chern, physicists [Chen Ning] Yang and [Tsung-Dao] Lee, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics for their work here. I am not sure even someone as well-connected as Oppenheimer could arrange such visas today. This is just one example of how the Institute is of this world and subject to its changes.

But wherever you come from, and however much the world may change, I trust you will agree that this locus amoenus—this special temporality, this time of mind, and this commitment to the testing of ideas—is precious. You may feel that such values are under threat, even in universities that claim to be built upon them, perhaps even in the places you have come from. All the more reason to celebrate that today you are entering a space as dedicated to the freedom and possibilities of thought as any place can be. Like paradise—which, we are told, did not last long—such spaces are fragile. But I do not fear for the Institute, so long as we cultivate our single reason for existence: to provide the most promising talent from around the globe the opportunity to realize its potential for advanced study, and so long as we remain committed to dialogue across differing convictions and commitments.

I urge you to pursue such dialogue, in any direction you wish—even, if necessary, by switching tables in the dining hall. You will encounter many voices among our Faculty, Members, Visitors, supporters, and critics. That diversity of voices is the necessary foundation for debate, for diagnosis in the Greek sense, for discovery. Equally necessary is the awareness that none of these voices speaks for the Institute, nor does the Institute claim to speak for you, since articulating a collective position would endanger the freedom of dissent that is essential for your own thought to thrive. These must be the enduring commitments of an institution founded not as a platform, but as a community dedicated to inquiry at its most profound.

That work has not changed as much as one might think since the early days, and Oppenheimer’s words about our purpose remain as true today as when he spoke them in a radio lecture in 1953:

I see that my welcome is becoming a sermon, and I am becoming a little emotional, so I will conclude with an appropriate blessing:

May every instant of your coming year in this space of human community—dedicated solely to the exploration of ideas at their most difficult—bring you a renewed sense of the possibilities for your own thought and your own discovery. Thank you for being here. Welcome to the Institute, and I invite you to a great party outside.