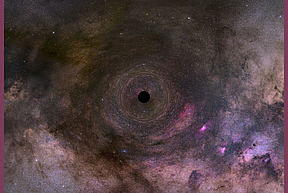

Black Holes

In a paper written in 1939, Albert Einstein attempted to reject the notion of black holes that his theory of general relativity and gravity, published more than two decades earlier, seemed to predict. “The essential result of this investigation,” claimed Einstein, who at the time was six years into his appointment as a Professor at the Institute, “is a clear understanding as to why the ‘Schwarzschild singularities’ do not exist in physical reality.” Schwarzschild singularities, later coined “black holes” by John Wheeler, former Member in the School of Mathematics, describe objects that are so massive and compact that time disappears and space becomes infinite. The same year that Einstein sought to discount the existence of black holes, J. Robert Oppenheimer, who would become Director of the Institute in 1947, and his student Hartland S. Snyder used Einstein’s theory of general relativity to show how black holes could form.