What actually happens when something falls into a black hole? While this question might seem simple, it has opened up one of the most profound mysteries in modern science.

Objects that fall into black holes possess specific properties—such as position, velocity, charge, and spin—which together constitute their “information.” According to Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity, known as general relativity—which governs everything from an apple falling from a tree to the movement of stars and galaxies—when this information crosses a black hole’s event horizon, much of it is lost forever. But quantum mechanics, which governs the world of the small—the strange realm in which a particle can move through solid objects and be in two places simultaneously—insists that information is never created or destroyed.

These two principles cannot both be true, and the contradiction they create is known as “the black hole information paradox.”

The work of renowned physicist Stephen Hawking complicated the puzzle further. He showed that black holes slowly evaporate over extremely long timescales, emitting thermal (or “Hawking”) radiation as they do so. Models of this evaporation suggest that the information content of a black hole is irretrievable when it dissipates. The same paradox arises in this context: if black holes do erase information in this way, the foundations of quantum theory would again be shaken.

Resolving this deep conflict between the principles of gravity and quantum mechanics—and more generally, developing a theory of “quantum gravity”—is a major open question in theoretical physics. By building on and extending one another’s research, IAS scholars have made substantial progress in this area, generating insights that continue to influence research.

Integral foundations were laid by founding Professor (1933–55) Albert Einstein, who published, alongside his IAS collaborators, two influential papers: one on quantum entanglement and another on so-called “wormholes.” At first glance, these papers seem to have little to do with one another, but breakthroughs by Juan Maldacena, Carl P. Feinberg Professor in the School of Natural Sciences, and Leonard Susskind, Member (1997, 2026) and Visitor (1995) in the School, conjectured a significant connection between them. Further connections that shed light on quantum gravity have been proposed by today’s generation of IAS postdoctoral scholars, including Beatrix Muehlmann, Leinweber Physics Member in the School. Her work provides a tantalizing next step towards understanding quantum gravity in our universe.

A Glove in Princeton, A Glove in Paris

The journey begins in 1935, when Albert Einstein, along with Boris Podolsky, Member (1934–35) in the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences, and Nathan Rosen, Member (1934–36) in the School, published the results of a thought experiment that began with a conversation at IAS teatime. Their paper, now known as simply “EPR,” after the three scholars’ last initials, questioned whether quantum mechanics truly describes reality. It made front-page news.

At the heart of the issue was what Einstein described as “spooky action at a distance,”1 namely that measuring the properties of one quantum particle in an entangled pair seemed to have an instantaneous effect on the state of the other, regardless of the distance by which the particles in the pair were separated.

This troubled Einstein, as it appeared to violate a fundamental principle of relativity: that information cannot be transmitted faster than the speed of light. For Einstein and his colleagues, the fact that information could seemingly be shared more quickly than this between pairs of entangled particles suggested that quantum mechanics did not provide a complete description of reality.

However, the EPR argument was based on a false assumption. Entangled particles do not communicate instantaneously, telling each other how to behave from a great distance—rather, their connection is the result of a fundamental “quantum correlation.” The correlation between the particles means that when you measure one, you learn about the other, without information having to pass between the two.

As an analogy, imagine a pair of gloves: you place one glove in a box and send it to Paris and keep the other in a box in Princeton. If your friend in Paris opens their box and finds a left glove, they immediately know that you have the right one, regardless of the distance between you. There is no mysterious, faster-than-light communication. The key difference in the case of quantum particles is that they do not start out with definite identities like the left and right glove each did. Like Schrödinger’s cat, which is neither alive nor dead until the box is opened, the particles do not possess any fixed qualities until they are observed.

Thus, despite being imperfect, the EPR paper was nevertheless a significant milestone in understanding quantum entanglement.

Tunnels Through Space

Einstein’s contributions did not stop there. In that same year, he joined forces once again with Rosen (just “ER” this time!) to describe another kind of connection that can be understood by opening a closet. Instead of reaching for a pair of gloves, imagine that the universe takes the form of a giant bedsheet, laid out flat on the floor.

Typically, if you want to travel from one point to another in the universe, you would have to move across its flat surface. But what if you could fold a sheet-like universe and connect those two points directly with a tunnel?

That’s what Einstein and Rosen proposed in their paper, a bridge connecting two distant places in a universe, making it possible (in theory) to travel between them much more quickly. This connection is called an Einstein-Rosen bridge, but is also now known as a “wormhole.”

Such wormholes are a mathematical consequence of Einstein’s theories of general relativity: when scientists use Einstein’s equations to describe how gravity shapes space and time, these equations naturally allow for the possibility of wormholes. But only in certain conditions.

One of the specific contexts in which wormholes can arise is Anti-de Sitter (AdS) space. Crucially, AdS space functions like the folded bedsheet, i.e., it can have a constant negative curvature, taking the form of a saddle shape. It is these features that, theoretically, would allow the wormholes to be formed.

It was within this AdS framework that a remarkable new connection was uncovered—one that would ultimately tie Einstein’s work on wormholes with his insights into quantum entanglement, setting the stage for a revolutionary unification of these concepts.

Building Bridges with Quantum Threads

Enter Juan Maldacena and Leonard Susskind. In 2013, they joined forces to ask: What if the two kinds of connections identified by Einstein—entanglement and wormholes—are not just similar, but actually the same? Their bold conjecture, known as ER=EPR, is what unites Einstein’s seemingly unrelated papers.

In an article based on a lecture that he delivered at IAS in 2016, Susskind summarized the ER=EPR conjecture as follows: “the immensely complicated network of entangled subsystems that comprises the universe is also an immensely complicated (and technically complex) network of Einstein-Rosen bridges.”2

In summary, he and Maldacena proposed that any two particles connected by entanglement are effectively joined by a tiny, quantum wormhole. The reverse is also true: they suggested that the connection that physicists call a wormhole is equivalent to entanglement. ER and EPR are two different ways of describing the same underlying reality.

At the heart of this proposal lies the principle of duality. Duality most famously arises in string theory, where it was recognized by Maldacena in 1997, as part of the Anti-de Sitter/Conformal Field Theory correspondence (AdS/CFT for short).

To understand AdS/CFT, imagine a snow globe, where everything happening inside—the swirling snow, the miniature trees and houses—can be perfectly described by information etched on the glass surface. Maldacena’s insight was that a universe with gravity (the snow globe) could be fully described by a quantum theory on its boundary (the glass). This so-called “holographic principle” suggests that the universe, in some sense, is a grand illusion: our three-dimensional reality may be encoded in two dimensions, like a hologram.

In this way, everything that happens inside Anti-de Sitter space is defined by the boundary. If you understand the boundary, you understand the interior. There is duality between the two.

AdS/CFT forms the mathematical basis for the ER=EPR conjecture. In ER=EPR, the entanglement between quantum systems on the boundary of space is reflected as a wormhole in the interior.

If ER=EPR is correct, it would provide a deeper understanding of the very fabric of spacetime, suggesting that the geometry of our universe emerges from the quantum phenomenon of entanglement. This is a radical shift in perspective. For centuries, space and time were seen as the stage on which the drama of the universe unfolds. Now, they may be the product of the drama itself—a web spun from the interactions and entanglements of quantum particles.

Whether the conjecture applies to our universe, however, remains an open question.

Beyond AdS: Quantum Gravity in our Universe?

The breakthroughs of Maldacena and Susskind have vastly improved our understanding of quantum theory in Anti-de Sitter universes, but our own universe does not exist in such a space—it does not have a negative curvature.

Instead, “a good approximation” for our universe, says Beatrix Muehlmann, is provided by de Sitter space. de Sitter space describes a spacetime expanding at an accelerated rate, like our own universe.

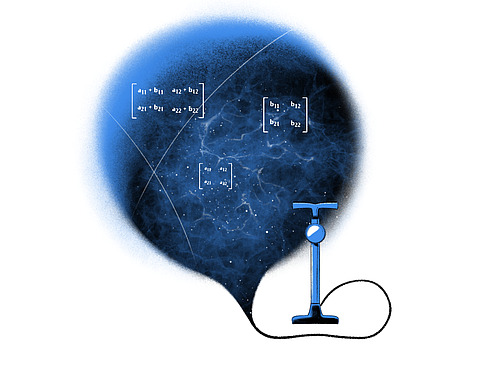

In a recent paper with colleagues Scott Collier from Syracuse University and Lorenz Eberhardt, Marvin L. Goldberger Member (2019–23) in the School of Natural Sciences, Muehlmann has provided a concrete, calculable blueprint for quantum gravity in de Sitter space through considering a simplified, “toy” universe.3

Crucially, the toy universe in which they have developed this framework has only two dimensions of space and one of time. It is known as dS3 space. This low-dimensional approach has enabled them to generate key insights. “We took this approach so that the math needed to make the calculations stays manageable,” explains Muehlmann.

Within this setting, they have proposed a new kind of duality. They have shown that a special “double-scaled matrix integral,” which comprises huge grids of random numbers, provides a means to calculate properties of the so-called “cosmological horizon” of their dS3 universe. This is the boundary in spacetime that marks the limit of the observable universe.

“Our own universe has a cosmological horizon,” states Muehlmann. “It’s around ten billion light years away from us. We don’t know what’s behind it!”

As well as establishing this key duality, she and her colleagues have shown how to calculate the entropy of the horizon of this universe using the same matrix model. Entropy is a measure of how disordered a system is—or, more precisely, how many ways it can be rearranged microscopically without changing its macroscopic state.

As a simplified example,4 imagine you were given a stack of ten coins, and told that just one coin in the stack must be placed heads up and all the others tails up. Without swapping the order of any coins, there would be precisely ten arrangements of heads and tails you could make which would achieve this outcome. But if you were told instead that five of the coins must be heads up and five tails up, there would be a much larger number of possible arrangements (252, to be precise). Entropy is bigger when many different detailed arrangements of a system give rise to the same broad description. Therefore, the “five heads up” state has higher entropy than the “one head up” state.

The horizon of a de Sitter universe is known to have a high entropy, and Muehlmann and her colleagues found a new way to precisely calculate it. To do this, they again reformulated the problem into the language of random matrices,5 and identified the density of eigenvalues of these matrices. When they integrated this density over a specific regime, they reproduced the entropy of the dS3 horizon as originally calculated by Gary Gibbons and Stephen Hawking in the 1970s.

Recovering this classic result was significant. It showed that Muehlmann and her collaborators’ work enables the difficult quantum gravity problem of an expanding universe to be “compressed” into the mathematics of random matrices. Through their research, the complicated system at the edge of a universe becomes a cleaner, computable object.

The universe in which Muehlmann and her colleagues are working is, of course, a stripped down model in low dimensions, and it does not incorporate realistic matter, but their findings are important nevertheless. “Low dimensional models really allow you to calculate things!” she says.

She sees the next important breakthroughs as coming from such regimes. “Through working in, for example, two dimensions, we can gain something meaningful,” she concludes. “Ultimately, we will be able to learn something that can tell us about the real world.”

From Einstein’s early insights to ER=EPR and the holographic revolution, IAS scholars have repeatedly shown how bold ideas can recast old paradoxes as solvable questions. And today, by pushing beyond AdS and crafting computable, low-dimensional models, scholars are closer than ever before to understanding how quantum gravity fits within our expanding universe.

[1] The phrase “spooky action at a distance” was not contained within the EPR paper itself, but is an expression that Einstein used later to describe the phenomenon of quantum entanglement.

[2] Susskind, L. 2016. “Copenhagen vs Everett, Teleportation, and ER=EPR.” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1604.02589

[3] Collier, S., Eberhardt, L., and Muehlmann, B. 2025. “A microscopic realization of dS3.” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.01486

[4] While the coin example illustrates how entropy counts the number of microscopic arrangements compatible with a macroscopic state, in the context of dS space, the precise meaning of entropy remains an open question. Scholars do not yet know exactly what, if anything, the entropy of a de Sitter horizon is counting. It could correspond to the number of underlying microstates, as in the coin example, but it might also be related to entanglement entropy, or something else entirely.

[5] More precisely, they reformulated the problem in terms of a double scaled 2 matrix integral.