Of Historical Note: Nuclear Fission

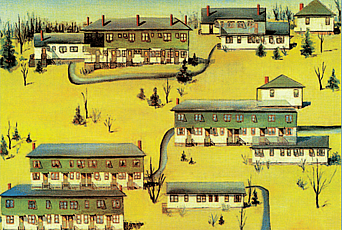

The following excerpt is from remarks given by John Archibald Wheeler on March 27, 2000, in connection with the play Copenhagen by Michael Frayn. Wheeler was a Professor of Physics at Princeton University from 1938 until his retirement in 1976 and a Member of the Institute’s School of Mathematics (prior to the founding of the School of Natural Sciences) in the spring of 1937, when it was still temporarily housed in Fine Hall (now Jones Hall) at Princeton University. Niels Bohr, who had a twenty-year association with the Institute, first visited in the academic year 1938–39, when the Institute completed Fuld Hall.

If two such great thinkers as Bohr and Einstein, who had such a high regard for each other, could be brought together for a prolonged period, would not something emerge of great value to all of us? This thought and this hope animated the guiding spirits of the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study to invite Niels Bohr to come as a guest of the Institute for the entire spring semester of 1939. However, four days before Bohr boarded his America-bound ship, he learned from Otto Robert Frisch that Frisch and his aunt Lisa Meitner had solid evidence that a neutron splits the nucleus of uranium. As he crossed the Atlantic, Bohr’s vision turned more and more from the problem of quantum mechanics to the problems of nuclear physics. So January and February, March and April of 1939 saw him working, discussing, calculating, and writing, day after day, not with Einstein on quantum physics as intended, but with me on the nuclear physics of fission. Yes, of course, there were meetings Bohr had with Einstein but they were occasional and did not lead to the big push it takes to formulate a solid well-argued position. No. Fission, and what it meant and how it differed from one nucleus to another, and what those differences offered in the way of using the nucleus for a chain reaction stood at the center of our attention. . . .

Close to us were our two Hungarian colleagues, Eugene Wigner and Leo Szilard, who had talked together confidentially many times of the possibility of arranging a nuclear chain reaction. On March 15, 1939, these hopes of theirs came to expression. On that day Bohr and I had a long meeting with Szilard and Wigner in the next-door office of Wigner (which had been the office of Einstein until, a few weeks earlier, Einstein moved to the new building of the Institute for Advanced Study).

Only a few days before, Bohr and I concluded that the fission observed in natural uranium originates in the rare constituent, Uranium-235, not in the 139 times more abundant U-238. “Then separate out the U-235” said Szilard, “and use it to make atomic bombs.” “That would be conceivable” Bohr replied. “But it would be an enormous enterprise. To carry it through would require the entire efforts of a nation.” Ultimately, it was to take the efforts of three nations, Britain, Canada, and the United States.

With discussions as passionate and fateful as those regarding fission going on, it is no wonder that the world lost forever equally passionate and fateful discussions on the quantum between Bohr and Einstein.

By May of 1939 Bohr was back in Denmark, despite the looming threat of war. . . . The paper by Bohr and me on the mechanism of nuclear fission appeared in the Physical Review of September 1, 1939, the same day the war began.