The Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center serves as a vital repository of the Institute’s intellectual and collective memory. Through its careful stewardship of records, correspondence, photographs, artifacts, and much more besides, the archive preserves the stories of the scholars who have shaped the Institute’s legacy and, by extension, the world of ideas.

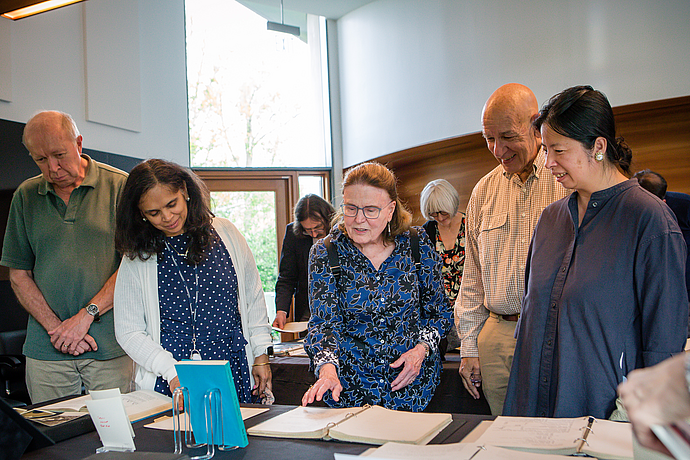

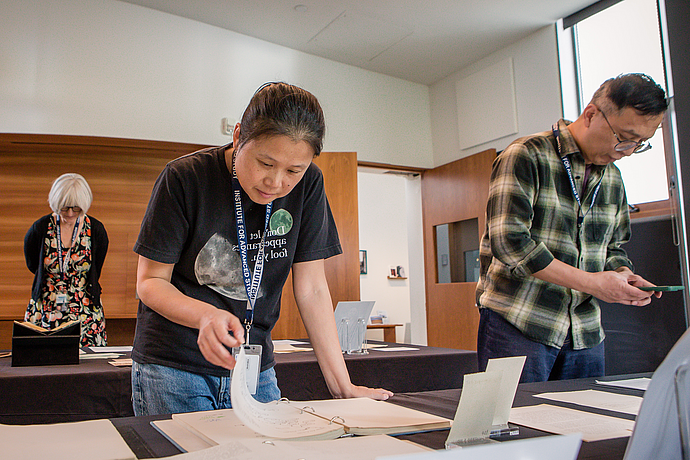

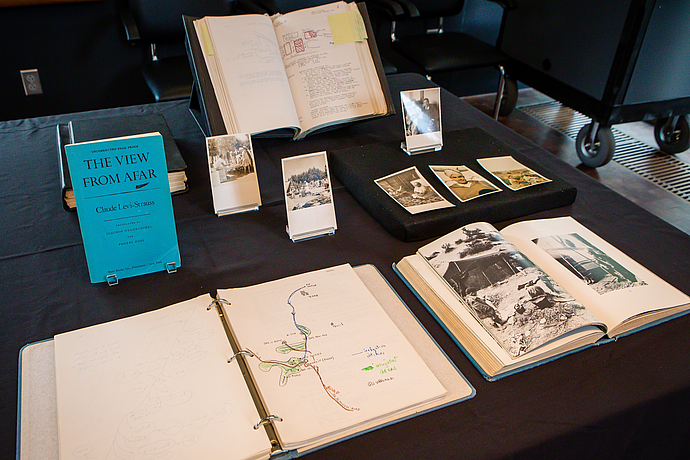

This year, the archive has made a remarkable array of new acquisitions—gifts and transfers that deepen the understanding of IAS history and the contributions of its scholars. These new items were put on display for the Institute community in September 2025 at a special pop-up exhibition hosted in Rubenstein Commons.

The new materials represent a cross-section of the Institute’s four Schools as well as a wide spectrum of the scholarly community. This includes Members, such as Wolfgang Pauli and Shiing-Shen Chern (陳省身), frequent Members in the Schools of Mathematics/Natural Sciences and Mathematics respectively, and those that served on the permanent Faculty, including Erwin Panofsky, Professor (1935–68) in the School of Historical Studies, and Clifford Geertz, Professor (1970–2006) in the School of Social Science.

Wolfgang Pauli: Archetypes and Annotations

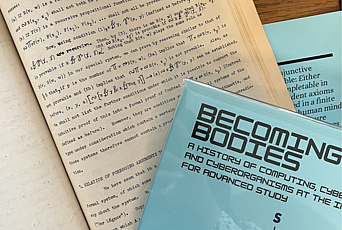

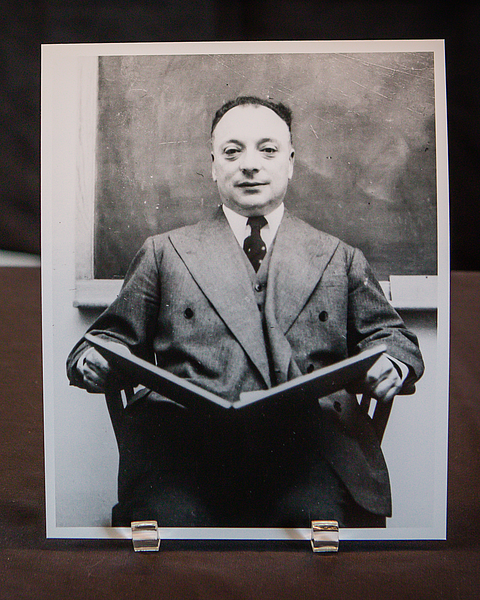

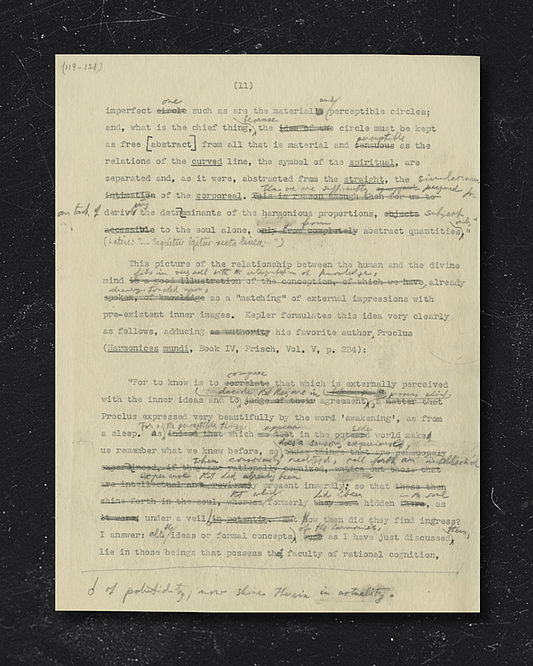

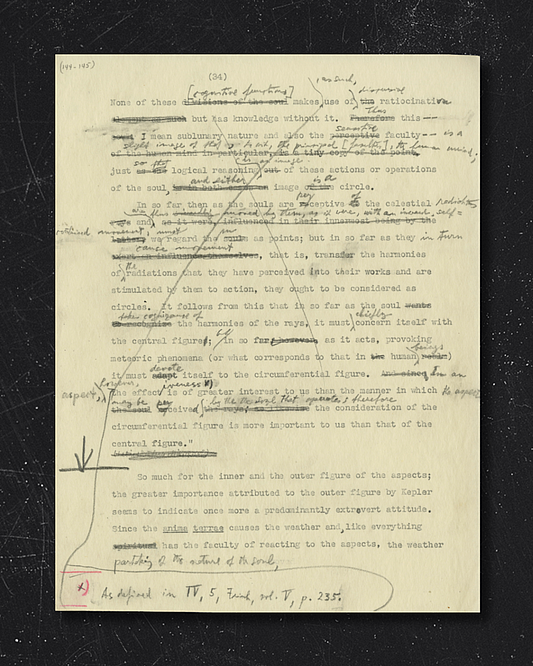

Among the treasures relating to the School of Natural Sciences is a typescript by the renowned physicist Wolfgang Pauli. The document is an annotated draft of a lecture Pauli presented at the Psychological Club in Zurich in 1948, which was later published under the title “The Influence of Archetypal Ideas on the Scientific Theories of Kepler.”

The “archetypal ideas” referenced in the title refer to the notion that mathematical and physical concepts possess both a quantitative, scientific meaning and a qualitative, symbolic, or “archetypal” meaning. Also mentioned in the title was Johannes Kepler, the influential seventeenth-century astronomer renowned for formulating the laws of planetary motion.

Pauli chose to study Kepler to investigate how modern scientific thought emerged from earlier, pre-scientific traditions that described nature in magical and symbolic terms. He was particularly drawn to Kepler’s explicit use of the concept of archetypes, which resonated closely with the ideas later developed by Carl Jung. Pauli was in close contact with Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the field of analytical psychology, when exploring this body of work.

In correspondence with physicist Markus Fierz, Member (1950) in the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences, written prior to delivering his lectures in Zurich, Pauli expanded on his motivations, noting his fascination with the transition from a magical-animistic worldview to the Newtonian understanding of space and time. This line of inquiry reflected a persistent unease Pauli felt regarding how space and time were treated in physics—he anticipated that these concepts might undergo further fundamental change.

The newly acquired typescript is particularly intriguing because it represents the process of translating scholarly ideas. Pauli’s lecture was originally written in German and he sought assistance in translating it into English. According to the Institute’s archivist, Caitlin Rizzo, “We believe that Erwin Panofsky helped Pauli with the translation, as there is a handwritten note stating, ‘Professor Panofsky says…’” Panofsky had previously undertaken similar translation efforts for his own writings and even discussed the experience in one of his essays. Pauli’s typescript exemplifies the interdisciplinary ethos that has long defined the Institute, fostering dialogue among physicists, historians, and philosophers to advance collective understanding.

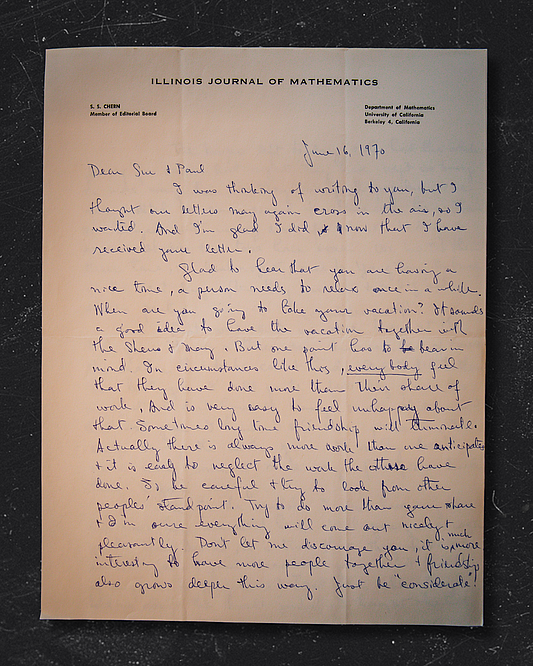

Shiing-Shen Chern (陳省身): Mathematics and Diaspora

From the School of Mathematics, the Shiing-Shen Chern (陳省身) family papers offer a rich portrait of Chern’s personal and professional life—highlighting not only his achievements as a mathematician, but also his role as a bridge between continents.

Chern first arrived in the United States in 1943 at the invitation of the Faculty of the School of Mathematics. During this period, Chern reflected: “I am inclined to think that among the people who have stayed at the Institute, I was one who has profited the most, but the other people may think the same way.” Indeed, Chern’s time at IAS proved fruitful for his career. He returned to China to found the Academica Sinica Institute of Mathematics before coming back to the United States at the request of André Weil, Professor (1958–98) in the School of Mathematics, who recruited him for a prestigious position at the University of Chicago. Chern’s work in the United States would later lead to a position at the University of California, Berkeley, which he held from 1961 to 1979.

Many of the newly-acquired letters from Chern and his family document this formative period of the family’s life in the United States. “These papers highlight the important role that Chern and his family played in aiding the education of scholars across the East Asian diaspora,” states Rizzo. The collection contains Chern’s letters to his wife, Shih-ning, about supporting talented mathematicians and helping them find a place in the U.S. education system. Letters from Chern’s children, Paul Chern and May Chu, document the struggles of Asian-Americans seeking an education amidst the political turmoil of the United States under the presidency of Richard Nixon. They include references to police raids and racial upheaval as a fixture of university life in the period.

In addition to the personal letters between close family and friends, the collection also includes an intimate look at Chern’s professional view of his native country after many years abroad. In the typescript “Recent Developments in China” from 1980, Chern expresses a sense of ongoing concern for the state of higher education in China in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. Materials from his memorial in 2011, marking the centenary of his birth, round out the collection, offering a moving tribute to his enduring influence.

Gerda and Erwin Panofsky: Lives in Art and Letters

Related to the School of Historical Studies are the Gerda Soergel-Panofsky and Erwin Panofsky papers, a gift from Gerda’s estate. The papers span the length of a remarkable life devoted to art history, scholarship, and mentorship. Among the collection is her Ph.D. dissertation, titled “Untersuchungen über den theoretischen Architekturentwurf von 1450 - 1550 in Italien,” along with the original plates, containing an impressive selection of images of Italian architecture. In addition to this, the collection contains some of her original scrapbooks from her first years at the Institute, including a photograph of the Historical Studies - Social Science Library. “This is the only photographic record that we have of the Library’s original reflecting pool,” states Rizzo.

Gerda Panofsky’s role as steward of her husband Erwin Panofsky’s legacy is also documented in the collection. The archival materials attest to the great efforts that Gerda made to prepare her husband’s remaining scholarly works for publication after he passed away in 1968. “She meticulously reconstructed the history of Panofksy's 1920 lecture ‘Rembrandt und das Judentum’ (Rembrandt and Judaism),” archivist Lorenza Pescia de Lellis explains. “She carefully edited the work for publication after Panofksy's death and even clarified points that the earlier lecture left unclear.” The lecture was published in the journal Jahrbuch der Hamburger Kunstsammlungen in 1974. Also among the archival treasures related to Panofsky's work on Rembrandt are his unpublished notes on the Dutch artist's c.1655 painting The Polish Rider.

The collection also includes extensive documentation from Gerda’s own travels and her second career after retirement, when she pursued a degree in Russian literature and documented her visits to Ukraine and Russia. “In her photographs, you can still see some of the landmarks that have since been destroyed by war,” Rizzo notes, underscoring the archival value of these photographs as records of a changing world.

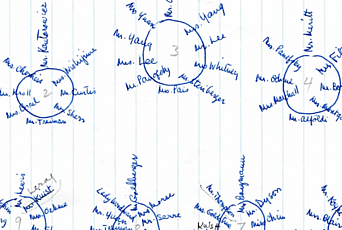

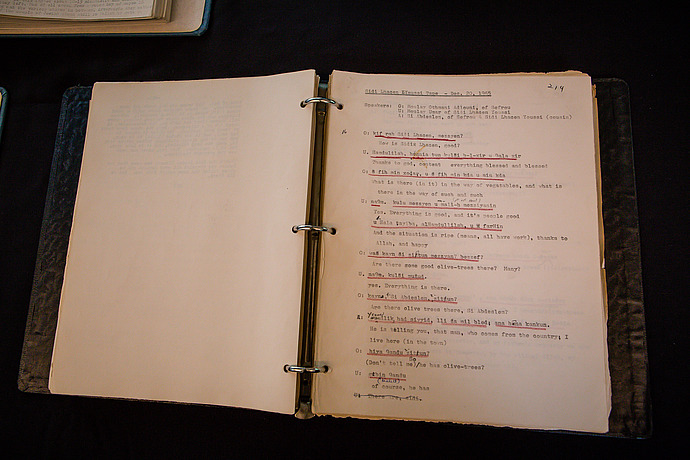

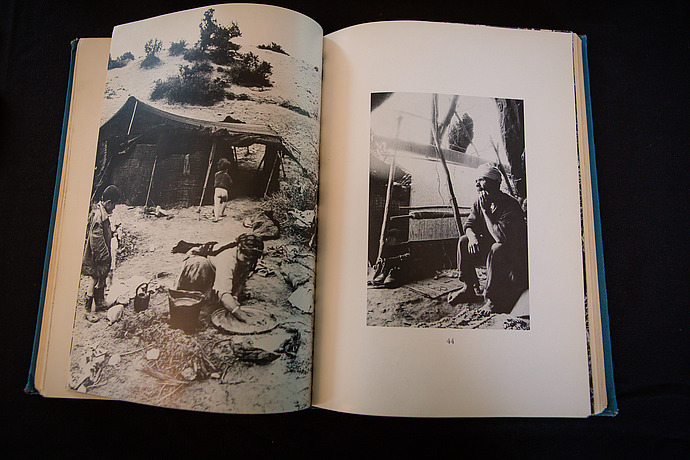

Clifford and Hildred Storey Geertz: Fieldwork in Morocco

Representing the School of Social Science, the newly acquired Clifford and Hildred Storey Geertz papers provide an intimate look at the research process of two of the twentieth century’s most influential anthropologists. As archivist Karen Clausen-Brown describes, “Most of what is represented in this collection relates to work that Clifford and Hildred conducted in the mid- to late 1960s in Morocco, in a region called Sefrou. The pair worked together and published separately and together based on the work that they did there. The collection contains many of their field notes, which include interviews with people that they met, as well as their observations, and photographs they took along the way.”

The collection is notable for its completeness, allowing viewers to trace the arc from field notes to the couple’s published scholarship. “Through these notes, we get an insight into their process of indexing their data and trying to put things into categories,” adds Clausen-Brown.

Some of the photographs among the newly acquired materials are from Clifford and Hildred’s personal field research collection, while others were taken by a professional photographer for publication. “Some of them show the same subjects, but the archival materials allow you to compare the more casual photographs and then the presentation photographs that end up in the book,” Clausen-Brown explains. This dual perspective allows researchers to unravel the ways in which anthropological fieldwork has been transformed into enduring scholarship.

The work of the Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center is ongoing. As the Institute continues to evolve, so too does its archive, ensuring that future generations of scholars will have access to the materials that illuminate the past and inspire the future.

The stewardship of these materials is not just a matter of preservation, but of active engagement—of bringing the stories of the Institute’s scholars into conversation with the present.