Grafting New Stems

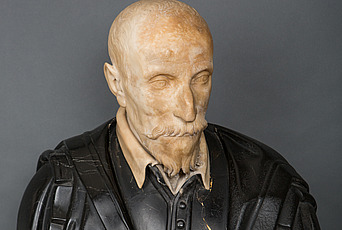

Back in 2020, in the midst of making yet another round of edits to my Ph.D. thesis, I put down my pen and picked up a paintbrush. The image shown above was the result: a representation of the face of Laocoön, a Trojan priest best known from the writings of the ancient Roman bard Virgil. Virgil’s epic poem The Aeneid describes how, toward the end of the Trojan War, Laocoön attempts to warn his people of the Greeks’ plot to capture their city by means of a wooden horse. Laocoön meets an untimely end: Virgil details how he and his sons were brutally assassinated by serpents sent by the vengeful goddess Athena, a supporter of the Greek cause, to silence him. Before reading the rest of this article, I invite you to gaze into the marbled face of Laocoön and ask the following questions:

- Do you like this painting?

- Why, or why not?

- Do you consider it to be authentic or original?

- Does it have value?

- If so, what kind of value?

Now that you have spent a few moments pondering the image, I can tell you a little more about it. In short, it is a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of an original. More precisely, it is a printed copy of a photograph; of a watercolor painting; of another photograph that I had taken at an art exhibition; of a plaster cast made by artist Orla O’Byrne in Cork, Ireland; of another plaster cast, a teaching model used to train artists at Cork’s Crawford Institute of Technology (CIT); of an original piece of ancient Roman sculpture, namely the statue group of Laocoön and his sons excavated in 1506 on the Esquiline Hill in Rome, now exhibited at the Vatican Museums.

At this point, the painting may appear less like a work of art and more like an onion, and there are potentially even more layers than those outlined above. To produce the watercolor, I printed off a hard copy of the photograph that I took at the art exhibition to allow me to better capture the play of light and shade when painting. There is also an unknown number of stages of copying between the CIT’s plaster cast and the original Laocoön statue group. It is likely that the CIT’s cast is itself modeled on another plaster reproduction. We must also consider whether the Laocoön in the Vatican that we refer to as an ‘original’ was likewise the result of copying processes. It is doubtful that it was made in a single moment of artistic inspiration in the workshop of the ancient sculptors to whom Roman writer Pliny the Elder attributes the piece. First drafts of sculptures produced in antiquity were regularly made in clay and then translated into the finished marble form. My watercolor could therefore be a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy of an ‘original’ that is itself the result of a copying process.

Another question now rears its head: has the revelation of the layers behind the image caused you to reconsider your answers to the questions above? If you answered ‘yes’ when initially asked ‘Do you like it?’ do the reasons that you identified still hold true? Or has the label of ‘copy’ changed how you view the piece? Ideas surrounding originals and copies, great masters and their imitators, and the value of so-called repetitive artworks are just a few of the many themes interrogated in the broad-reaching scholarship of Maria Hsiuya Loh, who joined the IAS School of Historical Studies as Professor in Art History on July 1, 2023.

As someone with a long-standing interest in reproductive artworks, I was especially intrigued by Loh’s first book, Titian Remade: Repetition and the Transformation of Early Modern Italian Art (2007). In Titian Remade, Loh directs a fresh gaze toward not only the work of famed Italian Renaissance artist Titian (ca. 1488–1576), but also that of another, lesser-known painter, most often described today as one of Titian’s imitators: Il Padovanino (1588–1649). Padovanino (born Alessandro Leone Varotari) was celebrated by his contemporaries, particularly for his portraiture. He was dubbed “our rising Titian” by English poet Sir Henry Wotton for his close replication of Titian’s characteristic themes, motifs, and style in his works, and his paintings featured in elite art collections all over Europe.

Even a cursory look at Padovanino’s oeuvre betrays its contact with Titian’s work. In Titian Remade, Loh considers Padovanino’s Sleeping Venus (ca. 1625), which is regularly associated with earlier depictions of the same motif, notably in another Sleeping Venus begun by Giorgione and completed by Titian (1508–10) and in Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538).

The three works have much in common. In each, the nude body of the goddess of love stretches across the canvas from left to right as she reclines on a pair of cushions. Her left arm and hand are carefully positioned to shield the full extent of her nudity and her right leg is delicately tucked under her left. However, differences also abound. Padovanino’s Venus is framed by a sumptuous red curtain on the left, from behind which an unpopulated landscape, complete with rolling hills, emerges on the right. As in Titian’s Sleeping Venus, the goddess’s right arm is tucked behind her head, but in Titian’s work, no curtain is present. Venus instead reclines entirely outdoors on a cream cloth. Meanwhile, the setting of the Venus of Urbino is a bedroom. Here, Venus’s eyes are open, glancing out at the viewer, and a small dog is curled up at her feet. Two maids behind her are shown preparing her dress. The similarities between the three images are not only limited to subject matter. Like Titian, Padovanino contrasts the luxurious, silken fabrics on which his Venus rests with the soft luminosity of her skin.

Each of these renderings of the recumbent Venus has the ability to intrigue and delight a viewer, yet only Titian’s works have achieved the status of great masterpieces in art historical literature. Despite being praised as Titian’s successor by his contemporaries, Padovanino has been maligned by more recent critics, Loh recounts, as “a belated imitator slinking about in Titian’s shadow.” In short, Padovanino’s paintings have been disparaged for precisely the same repetition of Titian-esque qualities for which they were praised in the past. In her volume, Loh draws attention to this reversal in Padovanino’s fortune, inviting her readers to reevaluate the significance of his work.

A method by which one might attempt to rehabilitate Padovanino’s reputation is through stressing his originality, highlighting the elements in his paintings that do stray from the Titian-esque and are very much his own. Loh explicitly rejects this approach. Instead, she chooses to embrace the repetition inherent in Padovanino’s work. She encourages her readers to shift their “critical vantage point” and reconsider the legitimacy of drawing such a sharp binary distinction between the concepts of ‘master’ and ‘copyist’ and ‘original’ and ‘copy’ in the first place. To introduce these ideas, Loh herself draws on the work of an IAS predecessor. She discusses an often overlooked essay by Erwin Panofsky, past Professor (1935–68) in the School of Historical Studies, which highlights Panofsky’s “fluid model of originals and facsimiles.” Panofsky’s essay was inspired by museum collections of plaster cast reproductions of sculptures, which had been painted to recall the material of their originals. In his discussion of these casts, Panofsky draws attention to the fact that such objects exist between the binary of “original” and “facsimile reproduction.” He described pure white, unpainted plaster casts as true facsimiles, for they were mechanically produced by means of molds and therefore lacked “the insertion of the human hand” in the making process. However, for Panofsky these same plaster casts existed in an intervening space between originals and copies when they were painted. This is because subjective, human choices were made when the painting of the casts occurred, likely in the precise colors and application of the paint. Painted plaster casts were thus neither wholly original nor fully a facsimile, problematizing the binary distinction that is often drawn between the two.

Significantly, Panofsky also argued that copies, including photographic facsimiles of paintings as well as plaster cast reproductions, possessed their own unique values. He presented these as primarily pedagogical in nature. He argued that by comparing a Cézanne watercolor to a printed reproduction of it, one’s understanding of the former work would be enhanced. This is because the comparison with the printed photograph would call attention to “certain attributes” in the watercolor “that would otherwise not have been marked.” In pointing out this educational value, Panofsky makes the point that originals and copies, in Loh’s words, exist “in a state of mutual dependency.” It is obvious that a copy is dependent on the existence of an original to come into being, but Panofsky’s essay makes the less obvious observation that our perception of and response to a so-called original work is capable of being transformed through our engagement with a copy.

Loh builds on this foundation laid by Panofsky by drawing on the work of French theorist Gilles Deleuze. Instead of a vertical, hierarchical approach that considers artists such as Padovanino as having been “inspired by” the great artists that preceded them, Loh encourages her readers to consider the relationship between Titian and Padovanino as being like a Deleuzian rhizome. The rhizome is a horizontal subterranean plant stem, characterized by its ability to develop in a nonlinear way. Rhizomatic systems have no specific origin or end: new shoots can graft onto older portions and, in Loh’s words, “transform the nature of both in the same instance.” Thinking about Titian and Padovanino as two parts of the same grand, art historical rhizome is likewise transformative for our understanding of both artists. Loh highlights how Padovanino’s reputation gained significance because of his references to Titian, describing how his paintings appeal to viewers when “we see Titian in them.” She interprets Padovanino’s artwork as functioning in a comparable manner to Hollywood remakes such as Terry Gilliam’s 1995 film Twelve Monkeys. As well as being a remake of Chris Marker’s 1962 film La jetée, Gilliam’s movie contains significant homages to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Loh articulates the pleasure that viewers who have familiarity with Hitchcock’s film experience when they encounter the allusions made to it by Gilliam. Unlike forged art pieces, which lose their value if they are successfully identified as such, Loh argues that remakes are instead deliberately referential. Their allusions are intended to be “found out” and enjoyed by their audience. This deliberate repetition is the kind that Loh identifies in Padovanino’s work, giving his viewers, steeped in knowledge of Titian, a satisfying feeling of being ‘in the know.’ The benefits of Padovanino’s association with Titian do not run in only one direction. Loh argues that the repetition of Titian’s work by Padovanino and others marked out his paintings as something worthy of being reproduced, increasing their standing as a result. In so doing, she highlights how both artists were transformed by the connections between them. She shows that considering how Titian “influenced” Padovanino is, in fact, the wrong question to ask. Instead, she advocates for a more ready consideration of how each artist changed the way that the other is viewed.

Just as Loh’s readers begin to understand Titian and Padovanino anew, as two stems grafted to each other in a state of mutual dependence, they also experience how Loh herself has spliced new roots onto past IAS scholarship, and not only that of Erwin Panofsky. In her consideration of the motif of the reclining Venus, Loh also follows in the footsteps of Millard Meiss, past Professor (1958–75) in the School of Historical Studies, who discussed the same theme in a 1966 essay titled Sleep in Venice: Ancient Myths and Renaissance Proclivities. Titian’s representations of Venus more generally were also brought to bear on the interpretation of the IAS seal in a short treatise by Irving Lavin, another past IAS Professor (1973–2019) in the School of Historical Studies, and his wife Marilyn Aronberg Lavin. Represented on the seal are the personified figures of Truth and Beauty, the former clothed, the latter nude. The Lavins’ essay highlights how theme of representing two Venuses experienced a resurgence in popularity during the Renaissance and, uncoincidentally, also appeared in one of Titian’s most famous paintings, known today as Sacred and Profane Love. The Lavins drew this detail into the history of the IAS seal, but noted that it was Panofsky who first outlined the Renaissance resurrection of the motif. In this rich context of interwoven scholarship, Loh’s appointment to the Faculty is sure to see the rhizome of art historical research at the Institute for Advanced Study continue to expand and thrive.

Maria Hsiyua Loh, Professor of Art History in the School of Historical Studies, is an internationally recognized expert in the field of early modern Italian art. Loh’s expertise also extends to contemporary artists, critics, and filmmakers, but it was her groundbreaking work on originality and repetition that caught the eye of Abbey Ellis, past Visitor (2021–22) and Research Associate (2022) in the School of Historical Studies, due to its relevance to her own research. Ellis’s Ph.D. project focused on the modern reception of plaster cast reproductions of ancient sculptures and issues of value and authenticity.