Studying Graffiti in an Ancient City: The Case of Aphrodisias

During Augustus’s reign (late first century B.C.E.), the philosopher Athenodoros returned from Rome to his hometown Tarsos, in southwest Turkey. When he found the city dominated by the poet and demagogue Boethos, he used the authority given to him by Augustus to send Boethos and his followers into exile. Thereupon, Boethos’s partisans wrote against him on the walls: “Deeds are for the young, counsels for the middle-aged, but farts for the old men.” When Athenodoros took the inscription as a joke, he ordered to add “thunders for old men.” But then someone, who despised all decency and had a loose belly, came in the night to his house and profusely bespattered the door and the wall. When Athenodoros brought accusations in the assembly against that faction, he said: “One may recognize the city’s illness and disaffection in many ways, and in particular from its excrement.”

This incident, narrated by the geographer Strabo,1 is one of the few references of ancient authors to graffiti. Another one is found in the Courtesans’ Dialogues composed by the satirist Lucian in the second half of the second century C.E. Two prostitutes, Drosis (“fresh as dew”) and Chelidonion (“the little sparrow”), discuss possible strategies against the philosopher Aristainetos, who was preventing Drosis’s lover, Kleinias, from visiting her. Chelidonion volunteers to help in a slander campaign: “I think that I will write on the wall in Kerameikos ‘Aristainetos is corrupting Kleinias.’” When Drosis wonders how Chelidonion can do this without being seen, her friend responds: “By night, Drosis, taking charcoal from somewhere.”

Graffiti such as these—children of the night, products of conflicts, and media of slander—existed in ancient cities in large numbers, mostly written with charcoal or paint on plastered walls. Large groups of graffiti have survived in Pompeii, in a subterranean construction in Smyrna, and in a large house in Ephesos.2 They were ephemeral texts, addressed to contemporary audiences, not to the future historian. Only those who knew names and contexts could understand them and appreciate the jokes. Most of such graffiti have been lost together with the wall plaster on which they were written. Together with them is lost also ephemeral poetry, such as the one described by the Roman poet Martial (12.61.7–10):

If you are eager to be read of, then look for some drunk poet of the dark archway, who writes poems with rough charcoal or crumbling chalk, which people read while they take a shit.

Graffiti are unofficial texts and images, expressions of thoughts and feelings of ordinary people. For this reason they are a valuable source for social, political, and cultural history, but only when a historian can place them in historical contexts and correlate them with other sources of information. Aphrodisias is one of the rare cases in which this is possible.

Aphrodisian graffiti: an overview

From the late first century B.C.E. to the seventh century C.E., Aphrodisias was one of the most important urban centers in Asia Minor. The city owed its name and its fame to the sanctuary of an old Anatolian goddess of fertility and war who, in the second century B.C.E. at the latest, was identified with the Greek Aphrodite. As a loyal ally of Rome, but also because Aphrodite was regarded ancestor of the Roman imperial family, Aphrodisias received political and economic privileges. Thanks to imperial support and the exploitation of marble quarries, the city of Aphrodite grew into a prosperous urban center and a leader in ancient sculpture. The New York University excavations, under Kenan Erim (1961–90) and Bert Smith (from 1991 onwards), have made Aphrodisias one of the most important archaeological sites in Asia Minor.

Almost all graffiti that had been incised or painted on plastered walls have now been lost, but the textual and pictorial graffiti that have been engraved and chiseled on marble have been preserved. Thousands of them have been recorded in the last decades.3 I can find no explanation for the great number, variety, and sometimes good quality of the Aphrodisian graffiti other than the fact that a substantial part of the population was involved in the carving of stone, as sculptors and masons. I assume that graffiti were primarily made by artists and workers who visited the theater, the stadium, and the markets with their implements. Graffiti, therefore, primarily reflect the thoughts and emotions of men—possibly also of children, apprentices in these crafts.

The Aphrodisian graffiti range from obscene texts and images (Figure 1), prayers, religious symbols, and simple personal names to representations of entertainers (Figure 2), gladiators, and wild animals, drawings of faces and objects, and acclamations for popular public figures, professional guilds, and teams of charioteers. Some of the pictorial graffiti are of high quality and resemble images in contemporary metal objects and glass vases (Figure 3). But some images are very rude sketches, resembling drawings made by children— and possibly, indeed made by children.

Exactly because of their non-monumental, private, and sometimes spontaneous nature, graffiti reflect in a more direct way than other categories of inscriptions the thoughts and feelings of simple people, about which other sources often are silent. Their backgrounds are, however, difficult to reconstruct. Only graffiti which belong to large groups or whose contexts are known can meaningfully be exploited as a source of information for everyday life and society. For instance, a quite accurate outline of the city wall scratched on the south wall can be roughly dated to ca. C.E. 365–370, that is, the construction period of the wall.4 And it provides the context for understanding another graffito engraved close to it. The text reads ORTHON (“Upright!”). It is the acclamation of workers or spectators when the construction of the fortification wall was completed: “May the city wall remain upright.” This wish was indeed fulfilled.

The following examples demonstrate how graffiti can provide information for interpersonal, social, and religious conflicts in Late Antique Aphrodisias.

Claiming professional space, cheering a team, insulting a governor

A graffito engraved on the huge retaining wall of the theater, which marks the south end of a large open space usually called the South Agora, reads “Place of Zotikos, the trader. Good luck” (Figure 4). Zotikos may have had a second booth at the northwest end of the South Agora, where we find another graffito: “Place of Zotikos.” On a column of the north colonnade of the same South Agora we read the word SOPHISTOU (“The place of the sophist”). It is here that in Late Antiquity a teacher of language and oratory met his pupils. Many graffiti in Aphrodisias are connected with the efforts of professionals—barbers, teachers, traders, etc.—to secure for themselves space in this area for their activity. Unfortunately, we have no information about whether they were assigned the space by civic authorities or by a professional guild, paying a fee. Nevertheless, such graffiti allow us to have a vivid impression of the various activities that took place in the public spaces.

As recent excavations in the South Agora by Andrew Wilson (University of Oxford) have shown, this public space, consisting of a large pool surrounded by porticos and a palm grove, was one of the most lively parts of the city, suitable for shopping, relaxed walks, but also agitated discussions among the followers of different statesmen, different religions, and different teams of charioteers. “The Fortune of the Red wins” is written by supporters of the red team on two slabs. Game boards engraved on the plaques of the pool and the pavement of the porticos, religious symbols on columns and pavements, images connected with shows and competitions, and acclamations provide valuable clues about activities but also about conflicts and tensions.

A graffito in a game board names a prominent figure (Figure 5): the provincial governor Dulcitius, who was involved in the restoration of the Agora Gate in the late fifth century C.E. The text is not well preserved, but it seems to be a joke on him. It probably reads “Eusebius screws Dulciti(u)s.” Obscene words such as this were used as insults. Their authors wanted to humiliate and insult their opponents. By ascribing them the passive part in sexual intercourse, they indicated that they were inferior and defeated. Since Dulcitius seems to have been a sympathizer of the traditional religion and Eusebius is a common Christian name, it is possible that the unknown conflict between Dulcitius and Eusebius was religious in nature: the conflict between a Christian and a “pagan.” At more or less the same time, acclamations at the west end of the same public space express the wish that the enemies of the Christian benefactor Albinus be thrown into the river (“The whole city says this: Your enemies to the river! May the great God grant this!”).

Graffiti as these help us somehow fill this and other public spaces of Aphrodisias with life and voices. PHILO EPIKRATEN (“I love Epikrates” or rather “I am a friend of Epikrates”) is written on a column of the Sebas teion, a building complex dedicated to the cult of the emperor. Is this an expression of genuine feelings or of flattery? Such graffiti often remain enigmatic, because their backgrounds are elusive. But sometimes we can be certain that they are expressions not of affection between equals but devotion in hierarchical relations. “I love Apollonios, the master” is written on a column, a declaration of a servant who wants his master to know about his devotion. Such declarations were public performances, texts meant to be read, possibly to be read aloud. They presuppose competition. The slave who declares his love to his master presupposes another slave who hates this (or a different) master. The friend of Hypsikles presupposes his enemy.

Religious conflicts

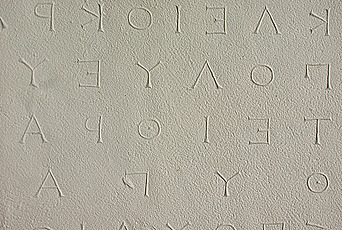

One particular form of competition and conflict was very prominent in Late Antiquity: the conflicts between religious groups. When Emperor Galerius put an end to the prosecution of the Christians and (for a short period of time) to the discrimination of the Jews in 311 C.E., an intense competition among religions emerged, which ended with the final victory of Christianity. In Aphrodisias, the resistance of the followers of the Hellenic religion lasted until the early sixth century. Supported by the imperial administrations, the Christians engraved religious symbols (crosses, fish), prayers, and acclamations on walls. One such graffito is worth a closer look (Figure 6). At first sight it looks like an abecedary, a list of letters of the Greek alphabet: alpha, beta, gamma, delta, epsilon. But zeta and eta do not appear in their proper places, before theta; instead, they are scratched above and below the other letters. The puzzle is solved when we observe that the letters are arranged in the form of a cross. In this arrangement, zeta and eta, together with the cursive beta (which resembles an omega), produce the word ZOE, “Life.” This is not part of the alphabet, but a Christian declaration of faith and hope in eternal life. We cannot determine whether this symbol was engraved before or after the end of Christian prosecutions, but it was certainly engraved in a period of religious competition.

Also, the opponents of Christianity have left their traces on the walls of the buildings. Numerous Jewish graffiti, usually menoroth, lamps with seven arms, can be seen in shops owned by Jews in the Sebasteion and the South Agora. As for the pagans, they responded to the Christian cross by engraving their own symbol, the double axe (labrys), the symbol of the Carian Zeus. Such graffiti reveal the importance of religious identities for the inhabitants of Aphrodisias and the bitter competition among Jews, Christians, and pagans.

The graffiti of Aphrodisias show that the study of the social history of an ancient city needs to take into consideration all types of evidence: texts and images, works of literature and documents, the masterpiece of an inspired and inspiring mind, and the humble expressions of the thoughts and feelings of ordinary people. This approach can be rewarding. It enables us to have a better picture of the dreams and nightmares, the hopes and the fears of human beings in times past. The graffiti, which are related with religious conflicts, address a very familiar issue: how religion divides and splits communities. Such graffiti are still relevant.

Recommended Reading: “Gladiator Fights Revealed in Ancient Graffiti,” Owen Jarus, Live Science (June 15, 2015): http://bit.ly/1G7tZHQ

1 Strabo 14.514.

2 Pompeii: e.g., R. E. Wallace, An Introduction to Wall Inscriptions from Pompeii and Herculaneum, Wauconda, Il. 2005; K. Milnor, Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii, Oxford 2014. Smyrna: R. S. Bagnall, Everyday Writing in the Graeco-Roman East, Berkeley/Los Angeles 2011. Ephesos: H. Taeuber, “Graffiti,” in F. Krinzinger et alii (eds.), Hanghaus 2 in Ephesos: Die Wohneinheiten 1 und 2. Baubefund, Ausstattung, Funde, Vienna 2010, 122–25 and 472–78.

3 For earlier collections of graffiti in Aphrodisias, see C. Roueché, Aphrodisias in Late Antiquity, London 1989; Performers and Partisans at Aphrodisias, London 1993; and “Late Roman and Byzantine Game Boards at Aphrodisias,” in I. Finkel (ed.), Ancient Board Games in Perspective, London 2007, 100–05; M. Langner, Antike Graffitizeichnungen: Motive, Gestaltung, und Bedeutung, Wiesbaden 2001. Many graffiti could be recorded from 1995 to 2014 by the author and members of the excavation team (especially Ioannis Mylonopoulos, Peter De Staebler, and Andrew Wilson). For an overview, see A. Chaniotis, “Graffiti in Aphrodisias: Images—Texts—Contexts,” in J. A. Baird and C. Taylor (eds.), Ancient Graffiti in Context, London 2011, 191–207.

4 P. De Staebler, “The City Wall and the Making of a Late- Antique Provincial Capital,” in C. Ratté and R. R. R. Smith (eds.), Aphrodisias Papers 4: New Research on the City and its Monuments (Journal of Roman Archaeology, Supplement 70), Portsmouth 2008, 284–318.