Gianmarco Caldini arrived at the Institute and saw no one. The Italian mathematician had fought through jetlag to step foot on campus as soon as possible, eager to begin a two-semester stint soaking up new ideas. But the storied American campus appeared vacant.

Perhaps he shouldn’t have been surprised. The Institute’s most iconic description is curiously anchored in absence: “[A] first-rate research institution with no teachers, no students, no classes, but only researchers protected from the vicissitudes and pressures of the outside world.”[1]

How well protected were these researchers? The network of footpaths connecting the Institute’s main buildings were empty. No figures dotted the distant reed-surrounded pond. Fuld Hall’s great clock tower stared blankly out onto motionless acres of trees and lawn, and inside that campus landmark Caldini found himself equally alone. On the second floor, he lingered in a small library where books marked by decades of hands and pens felt somehow less ghostly than the present population.

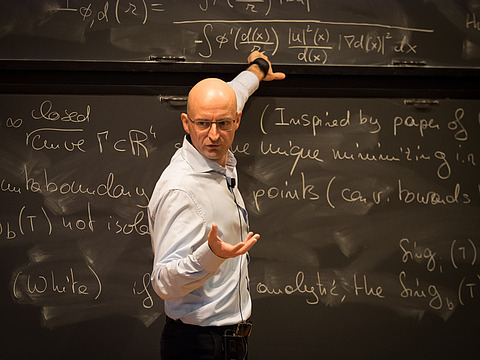

Outside, clouds gathered around the pale February sun, casting mist and shadows. The cool winter gloom—identical to the one he’d just left at the foot of the Dolomites—intensified his weariness. He decided to head back to his rented apartment on Parkside Drive. A doctoral student at the University of Trento with a scholarship funded in honor of renowned Italian economist Claudio Dematté, he came to IAS as a visiting graduate student to work with Camillo De Lellis, IBM von Neumann Professor in the School of Mathematics. Caldini didn’t qualify for on-campus residence at the Institute, but no matter, no trouble. He’d walk the short mile home and return in a few hours for a lecture. Simon Brendle—a world-famous geometer and von Neumann Fellow (2002–03) in the School—was slated to speak.

A few hours later, Caldini sat stunned, mind racing to keep up with the force and speed of ideas circulating around him.

Once darkened and silent, the School of Mathematics’ Simonyi Hall radiated bustle and energy. Names Caldini knew only as prefixes to famous theorems crowded in person alongside him. The familiar elegance of great mathematical thinking felt different here: vital and audacious and big. Like a forest clearing, the Institute had come to life in congregation.

Caldini had arrived at a place of harmonious extremes: a peaceful refuge for scholars to think freely without aim, and a collective vehicle for curiosity to flourish and cross-pollinate. For this reason, the Institute attracts fiercely independent intellects. And, for this reason, it also nourishes profound relationships.

Caldini was soon to the feel the influence of both. In just a few months, he’d have more than just his dissertation subject. He’d prove a theorem thirty years in the making and see his name listed next to several generations of the greatest thinkers of his time.

Sitting in Simonyi Hall, jetlagged and euphoric in the mathematical fracas, he didn’t yet realize how much it would all matter—the silence, the freedom, the companionship, and the apartment on Parkside Drive.

A mathematics half as sophisticated as soap

There are two broad ways to describe the mathematical field of topology. One is rubber geometry. The other is the study of holes.

Topology studies fundamental qualities of shapes and spaces. From a rubber perspective, we would ask: to what extent can a shape be deformed without losing its essential identity? We can bend and stretch a form in many ways while preserving its most important topological qualities and thus learn more about them.

The role of holes is key. To a topologist, holes are valuable elements that influence the quality of space. Voids and loops are landmarks in geometry that allow mathematicians to navigate, define, and classify structures—from the simplest shapes to spaces in higher dimensions so complex they are impossible to visualize.

At the heart of topology is the effort to taxonomize. Its categories, however, can come as a surprise. In a basic geometric sense, spheres and cubes are distinct. But from a topological point of view, they are the same: we can deform one into the other without cutting or gluing them, and they have no holes.

The most cited example of topology’s elastic sense of equivalence is the donut and the coffee cup. A topologist would say they are identical. Imagine the bottom of the cup brought up to meet its rim and then squeezed smaller to make a continuous curve with its handle. This shows that the donut and the mug are the same topological object, differently deformed. A hole is a hole is a hole.

“It’s as if topologists walk around with special glasses on,” Caldini said. “These glasses only allow them to see fundamental shapes, which gives them access to very profound information about structures and how to categorize them. This information is necessary to the work we do in our field of geometric measure theory. If we are explorers, then topology is our map.”

Caldini specializes in an area of math known as geometric measure theory (GMT), a branch related to but separate from topology. This field stands out for its ability to capture extraordinary levels of complexity. Unlike other branches of geometry, GMT provides tools to apprehend and analyze the structure of objects that may otherwise seem to be structureless. Messy, layered, obstructed, flawed, rough—these are the qualities of form that GMT is most suited to study. This works out nicely. For these are the qualities of form most often found in life.

GMT’s origins lie in the Plateau problem. In the mid-nineteenth century, Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau asked us to consider a wire loop. If we dip this wire loop into liquid soap, the soap forms a film over the hole’s surface. It does so with extraordinary efficiency, Plateau noted. The soap covers the loop with a minimum of surface area, naturally optimizing geometric form to conserve energy.

The catch is that nature’s problem-solving causes mathematical headaches. Math likes smooth structures. They make calculation possible. But when shapes form in nature, energy conservation may be better served by pinches, folds, corners, and jumps than smooth predictable planes. If mathematicians want to calculate the minimal surface of a complex shape half as well as soap can, they need advanced techniques to help. GMT provides those, forging measuring tools that hew closely as possible to these obstacles—known as singularities—that contain the richness and intelligence of life.

These were Caldini’s concerns—optimization, singularities, and smoothness—as he allowed his curiosity to lead him to his thesis subject. His advisor in Trento, Andrea Marchese, had been generous and open to possibility, and De Lellis—a foremost expert in the field of GMT—was encouraging him to find his own way. In the end, it was a footnote that caught Caldini’s eye.

“Who knows where they could be.”

The citation had been knocking around in his head since he’d first read the journal article as a master’s student in Italy a few years before: “F. Almgren and W. Browder, On smooth approximation of integral cycles, in preparation.”

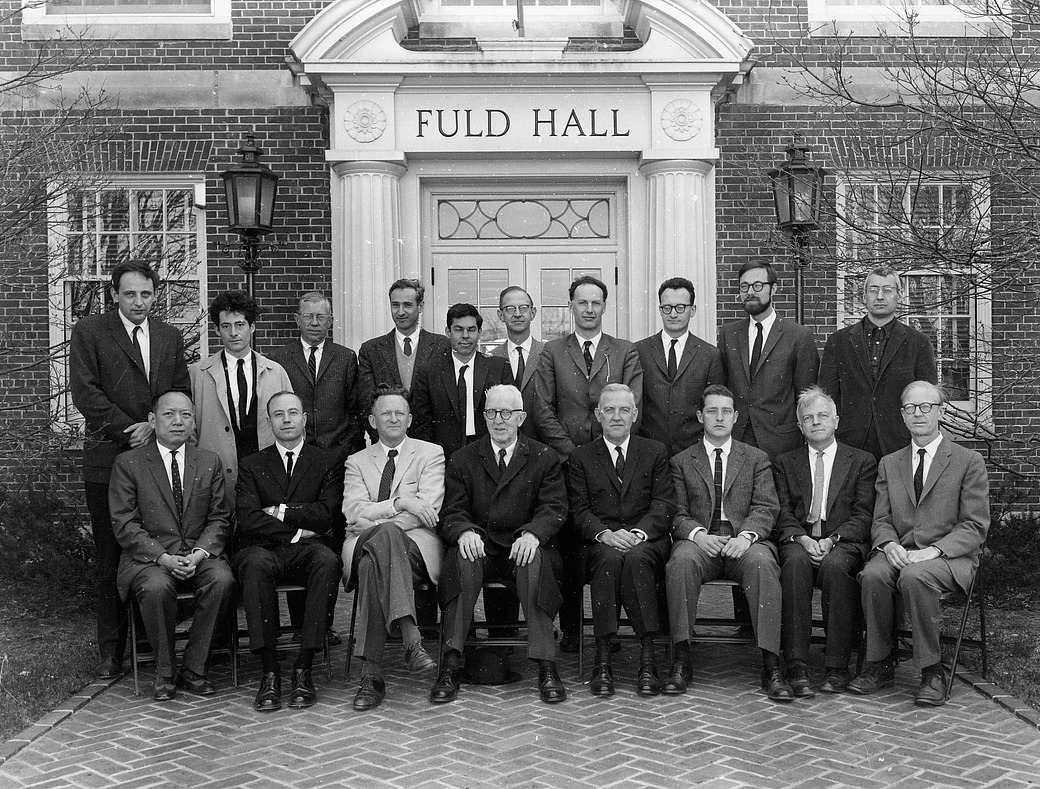

The article was written by Princeton University professor Frederick J. Almgren Jr., a foundational figure in GMT and frequent Member of the Institute’s School of Mathematics. Published in 1993, the paper was a broad review that listed and discussed key theorems and issues in the field.

One section piqued Caldini’s curiosity. It posed a fascinating question: “Can mass-minimizing integral currents be approximated by submanifolds?” That is to say: is it possible to find a smooth topological object that approximates a generalized surface—regardless of the complexity of its singularities?

Incredibly, under certain circumstances, the answer Almgren gave seemed to be “yes,” and the outlines of a method followed. At the end of the short section, it referred the reader to the forthcoming theorem for a full explanation. Eager to learn more, Caldini searched, but could find no resulting proof.

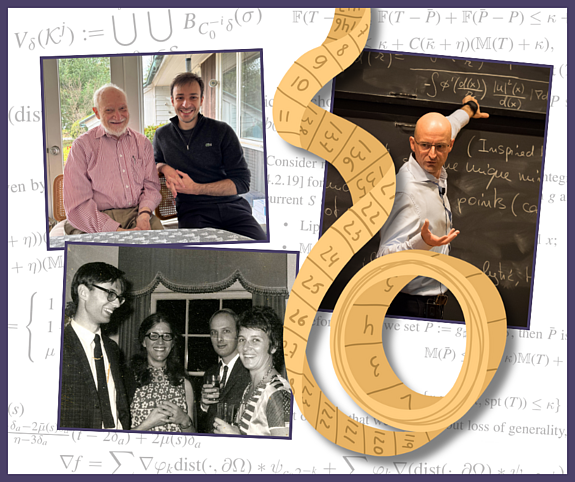

At the Institute, Caldini asked De Lellis if he knew where the theorem could be found.

“Almgren died suddenly in 1997,” De Lellis answered. “But I’ve asked Bill Browder the same question.”

Browder, a renowned topologist, had been a Princeton professor, as well as an IAS Member and Visitor many times over. His research laid the groundwork for algebraic and differential topology, deeply influencing generations of advanced discoveries and creating essential tools for its study.

“What did he say?” Caldini asked.

“He didn’t remember precisely. He mentioned having some notes he could look for,” De Lellis said. “After so many years, who knows where they could be.”

“Rugalach!”

Caldini didn’t miss Italian food at all. The dining hall at the Institute lived up to its reputation. Every day, he could count on a delicious meal: roasted fish, hearty soups, and crisp vegetables. And every day, he could find productive solitude or good company, where conversations with fellow scholars opened doors to corridors of thought he’d rarely encountered in such variety and depth. A single lunch could reveal the latest in physics or new insight into the excavation of Troy.

The coffee, however, was a problem. Weak. Light. In big steaming cups that broke his heart. He craved espresso daily.

It was his landlady who pointed him in the direction of a barista. And it was his landlady who invited him grocery shopping one Saturday morning. A former professor of criminal justice and law in New York, she regularly rented her home’s attached apartment to visiting academics and their families, enjoying her role in central New Jersey’s lively intellectual landscape. As her car began to follow the gentle curves of Parkside Drive, she asked Caldini what he studied.

“Our neighbor is a mathematician too,” she said. “Lovely man. We’ve spent holidays next door with him and his wife.”

“What’s his name?” he asked.

“Bill Browder.”

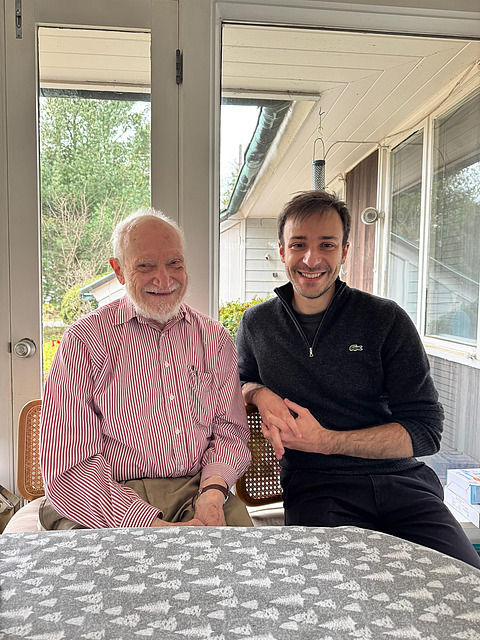

Within a week, Caldini found himself invited to the cozy house next door, low-set and private behind its broad lawn. He sat across from the legend (enthusiastic, nonagenarian, wry) and felt strangely at ease despite the stature of the company. The dining room, with its patterned cloth-covered table, looked out onto the backyard where a splash of red marked a feeder and collection of trinkets designed to attract hummingbirds. A plate of cookies Caldini had never heard of before (“Rugalach!”) lay at his elbow.

“The approximation theorem you announced with Fred Almgren in the nineties,” he ventured, “the one cited as in preparation. What ever happened to the proof?”

“I’m afraid,” Browder said, “it is still in preparation.”

Every Thursday, the two met at the dining table to work. Browder had found, somehow, the bulk of his collaborative work with Almgren beneath decades of paper in his study. After so many years, Browder and Caldini approached the problem afresh.

A technique and a point of view

“One of the most important things I learned from Bill was his way of approaching research,” Caldini said. “First, you need a subject. Something motivating to clasp onto. Then, you need to learn its alphabet and develop a technique. You must grasp the building blocks of your subject and create a method to use them well. But most importantly, you need your own independent point of view. That is what makes Bill’s work so incredible.”

An authentic point of view, Browder told Caldini, leads to solutions that, once discovered, manage to seem like the only ones possible. Every great result, every seemingly natural and singular success, transforms the general perception of the problem. In retrospect, it becomes difficult to remember how difficult the problem once seemed to be.

And so, with De Lellis, they worked on their perspectives. Browder shared the finer points of topology, and the geometric measure theorists wove in the capabilities of their field. Every week, the solution got closer. And every week, the friendship grew.

Sometimes a hummingbird would visit the feeder outside the dining room’s doors. Once Caldini raised his camera to catch the flash of feathers.

“Stop,” Browder said. “Put down the lens. Just look.”

The outside world

By Caldini’s second semester, the proof was finished.

It wasn’t without its challenges. The smooth approximation was working until their integral currents, or generalized surfaces, arrived at dimension seven. There, a singularity stopped them.

In the end, Browder’s topological perspective pointed to the solution: to overcome the obstruction, they needed to classify and understand it. With that information in hand, the geometers modified their approach, finding an adapted form that got them their approximation and solidified the theorem.

It was to be Browder’s last. A few weeks after Caldini returned home to Italy, Browder died in his home on Parkside Drive.

The Institute aims to protect its researchers from the outside world. Without the pressures of utility or necessity, the mind can find its own priorities: beauty, inquiry, truth. Often, from this sheltered haven, emerge means—ever more sensitive, ever more precise—to understand that world. To measure it. But over and above the outcomes, the perspective is the point.

This freedom? That curiosity, that peace? It’s the closest one can be to life. Put down the lens. Just look.

[1] Nasar, Sylvia. A Beautiful Mind: A Biography of John Forbes Nash, Jr., Winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, 1994. Simon & Schuster, 1998.