Research from the Margins

So ends a note written in a copy of Diophantus’s Arithmetica, a list of over 200 algebraic problems dating from around 250 C.E. The note, however, was penned much later, in the seventeenth century C.E., by Pierre de Fermat, a French lawyer and amateur mathematician.

It appeared next to Diophantus’s discussion of a problem reminiscent of the famous Pythagorean equation a2 + b2 = c2: how to split a given square number into two other squares.

Fermat made the bold claim that “it is impossible to separate a cube into two cubes, or a fourth power into two fourth powers, or in general, any power higher than the second, into two like powers.” But if Fermat did indeed have a proof of this theorem, it seems that he never committed it to paper.

Nevertheless, his tantalizing comment in the margins of the Arithmetica, posthumously published by his son, served as a spark, igniting a 350-year quest to (re)discover the elusive proof. Yet despite concerted efforts by generations of mathematicians, the theorem resisted proof, becoming known as “Fermat’s Last Theorem.” (Their efforts were not entirely in vain, of course, since attempts to prove the theorem brought about substantial development in the field of number theory.) The theorem’s long-standing unsolved status even saw it enter the popular imagination; it was dubbed “the most difficult mathematical problem” by the Guinness Book of World Records.

Finally, in 1994, Andrew Wiles, frequent Member and Visitor (2007–11) in the School of Mathematics, successfully proved the theorem after working on it in secret for seven years. It was formally published in 1995 to great acclaim. The centuries-long academic journey to the proof began with a single note.

Marginalia, in the form of not just notes but scribbles, doodles, corrections, and illuminations, is by no means confined to the realm of mathematics. And while in the case of Fermat’s Last Theorem such additions to printed texts were a key impetus for beginning the study of a problem, in other cases, marginalia are equally integral to a problem’s solution. Such notes—appearing in books and offprints, on photographs and squeezes, and on notecards—transform what might seem like static artifacts into dynamic records of scholarly engagement. They document the history of how scholars have interpreted, connected, and published ideas throughout time and space, creating a multilayered conversation that can even stretch across millennia.

The Institute has its own intriguing collection of marginalia. Some give insight into the character and work of IAS scholars, while others offer a glimpse into Institute history. More still offer themselves as opportunities for understanding engagement with texts over time, particularly those within the rare books collection, which includes a notable edition of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolvtionibus orbium coelestium, libri VI. These inscriptions are a visual representation of both the solitary study and the conversations through paper that profoundly enrich scholarship at the Institute, and will continue to do so as scholars carry on the storied tradition of scribbling.

Logicians in Conversation

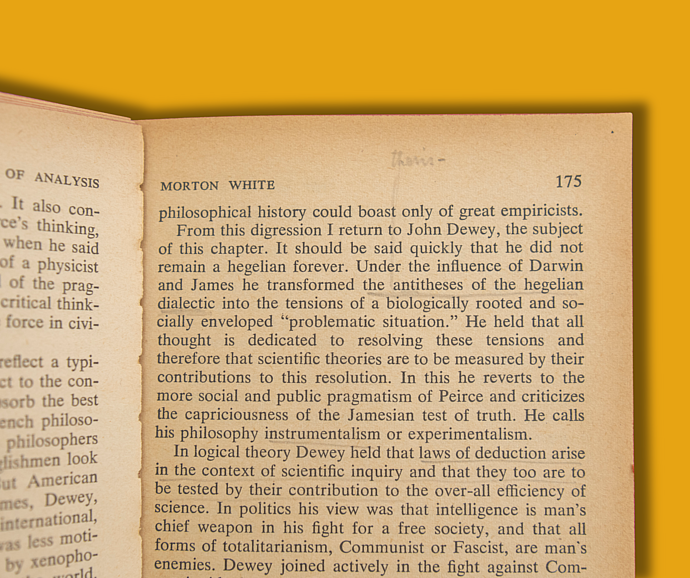

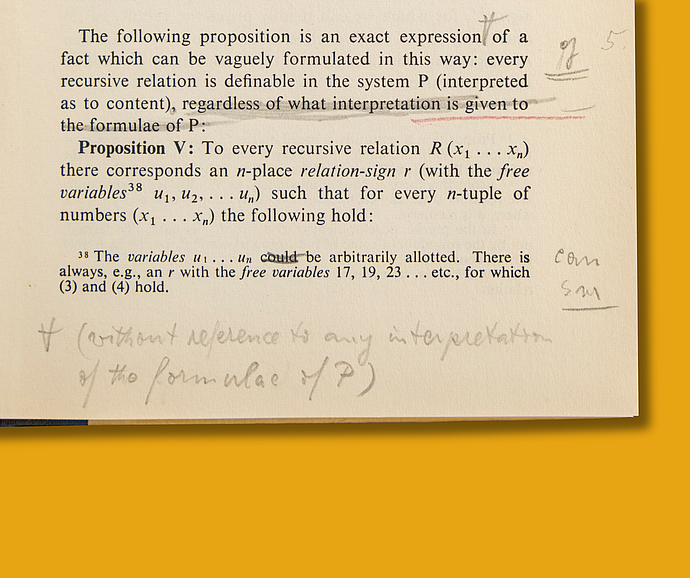

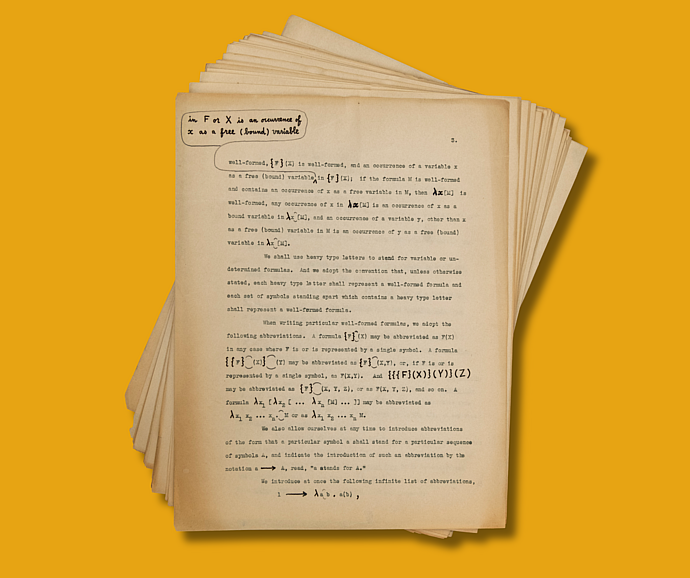

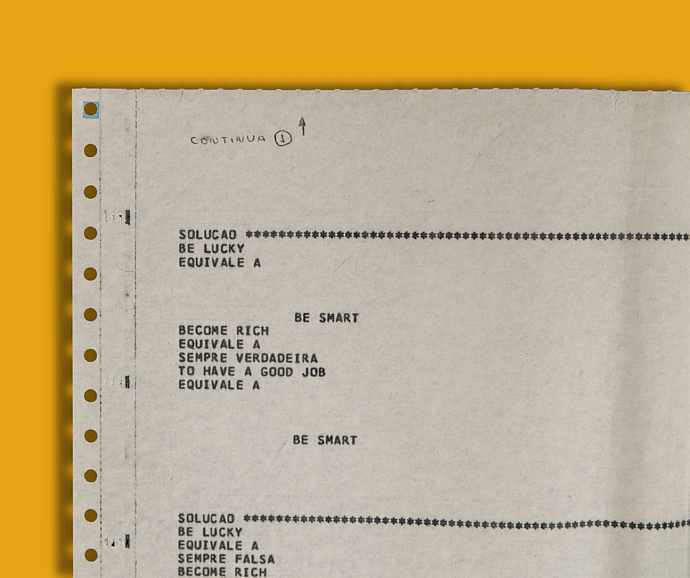

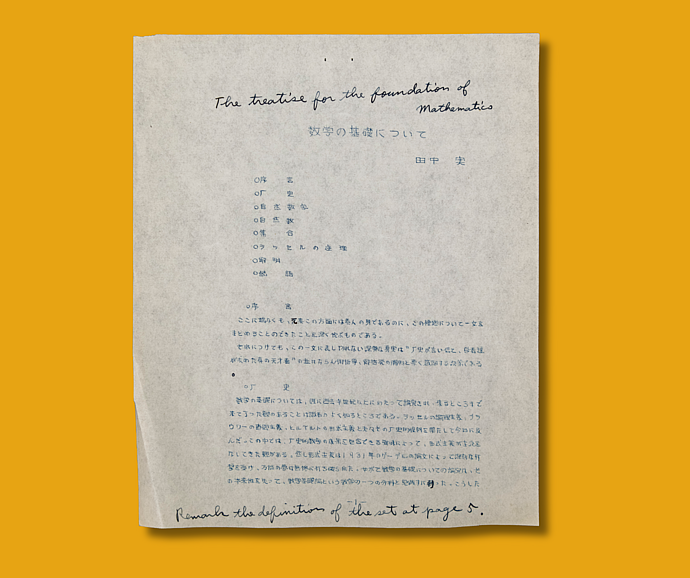

Philosophers and logicians Hao Wang, Visitor (1972, 1975–76) in the School of Mathematics, and Kurt Gödel, frequent Member and Professor (1953–78) in the School, engaged in extensive conversation over the mathematical systems that make up computers, with Wang becoming known as a Gödel commentator in the later parts of his career.

Wang was deeply interested in computer programs due to their uniform, rule-bound nature, which contrasted sharply with the more irregular patterns of human thinking. This fundamental difference between algorithmic computation and human cognition inspired Wang to develop computer programs capable of proving theorems in two distinct branches of logic: propositional calculus and predicate calculus.

This drew Wang to Gödel’s work, in particular his incompleteness theorems, which are integral to understanding modern-day computer programming. During their shared time at the Institute, Wang and Gödel had the opportunity to exchange both ideas and offprints in English and Japanese. Their dialogue is evident in these documents with numerous handwritten symbols, likely stemming from Gödel’s pen.

Letters of Correction

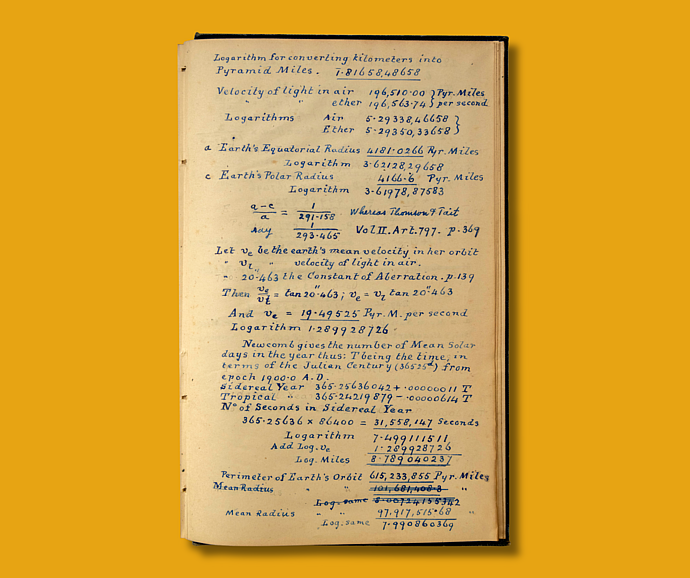

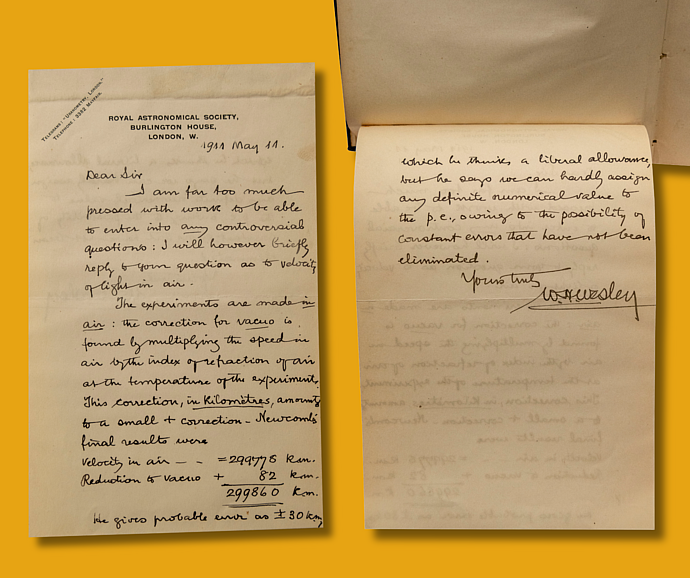

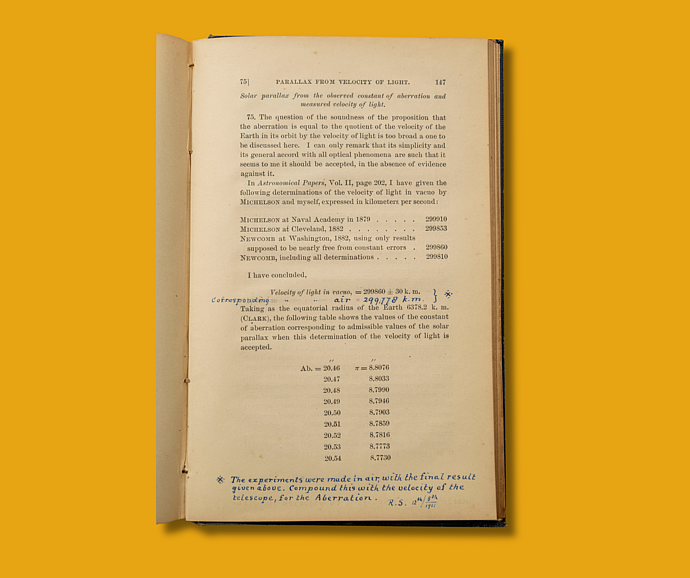

The pages of astronomer Simon Newcomb’s 1895 publication, The Elements of the Four Inner Planets and the Fundamental Constants of Astronomy, housed in the Institute’s rare book room, are filled with meticulously crafted logarithmic calculations. But most intriguing are the corrections to Newcomb’s calculations of light velocity in air, added by a subsequent reader. These amendments likely originated from correspondence found attached at the back of the book—possibly authored by William Henry Wesley of London’s Royal Astronomical Society—which appear to document discussions about the error between Wesley and the book’s owner.

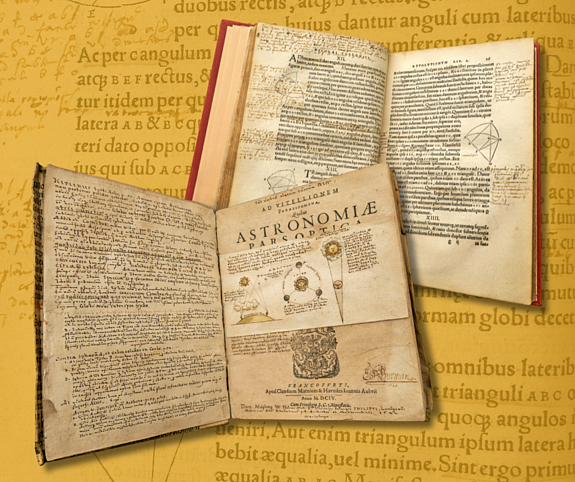

An Astronomical Palimpsest

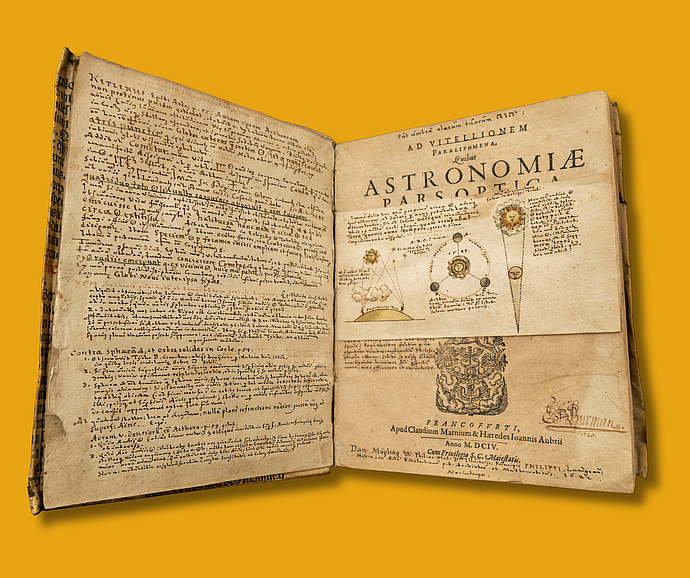

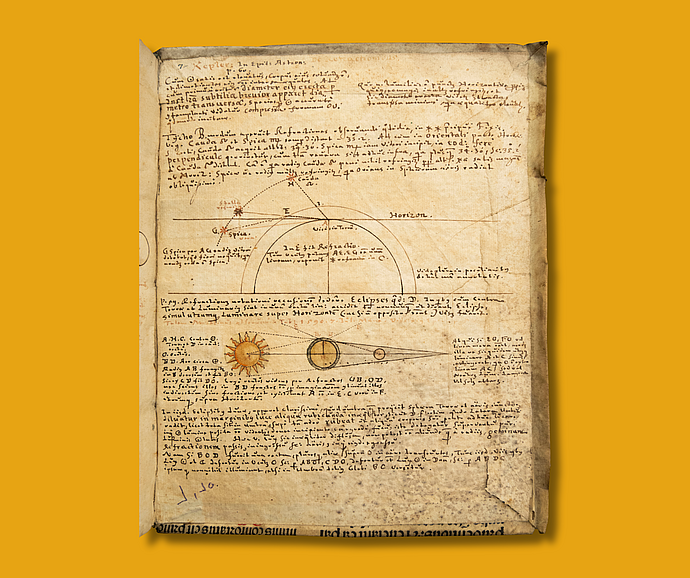

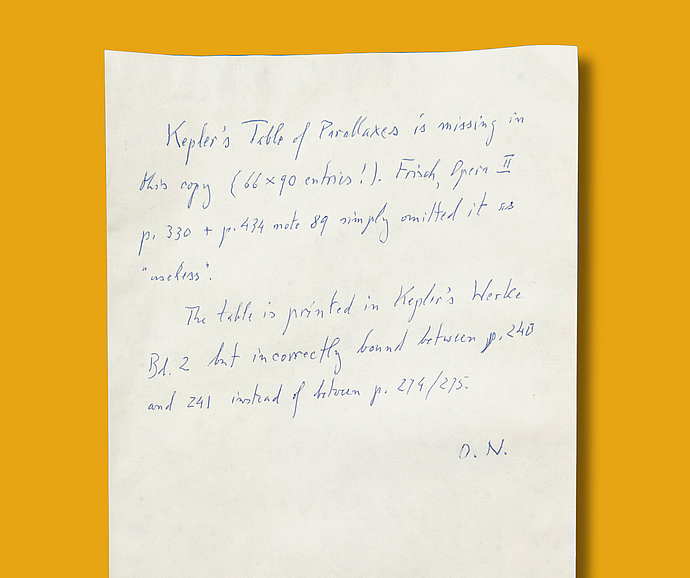

Alongside vivid illustrations of the solar system as it was understood in the early seventeenth century, the inside front and back covers of this edition of Johannes Kepler’s Ad Vitellionem paralipomena, quibus astronomiae pars optica traditvr (Supplement to Witelo, in which the Optical Part of Astronomy is Expounded) are filled with copious detailed annotations. In the back, some of these notes are faded, which could indicate that the page was washed to make space for new thoughts. In addition to the exquisite marginalia, a small sheet of paper tucked into the volume alerts future readers that this copy of the book is missing a table. The initials O. N. indicate that the note was written by mathematician-turned-historian of science Otto Neugebauer, a frequent Member of multiple IAS Schools, who contributed extensively to studies of the history of mathematical astronomy.

Squeezing History

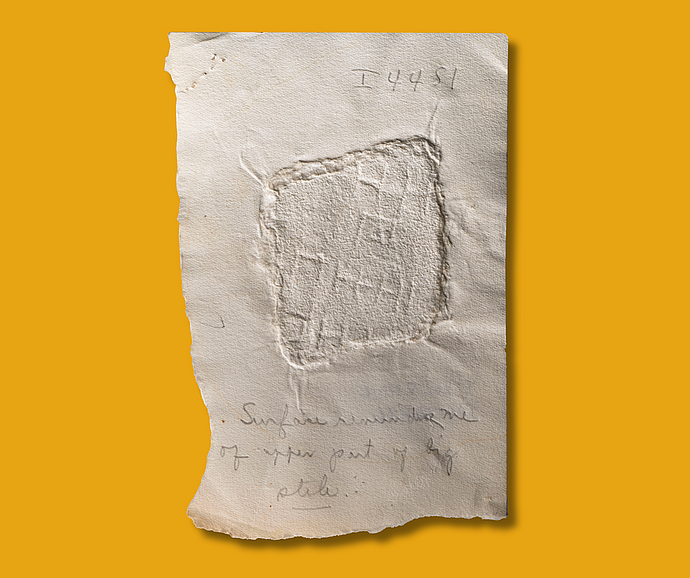

Epigraphic squeezes are three-dimensional paper replicas of ancient Greek and Latin inscriptions originally carved in stone. Created by pressing dampened paper onto inscribed surfaces and allowing it to dry, these impressions faithfully capture the texture and dimensions of inscriptions in a portable format that scholars—such as Benjamin Meritt, Professor (1935–89) in the School of Historical Studies, who founded the Institute’s squeeze collection—can study in the absence of the original artifacts.

This squeeze is of an inscription from the Athenian Agora (marketplace), which originally formed part of a list of tribute payments given to the city by its allies. The squeeze bears pencil annotations where a scholar noted, the “surface reminds me of the upper part of the big stele,” highlighting a crucial moment of insight that connects this small fragment to a larger known monument.

Beyond the squeezes themselves, the photographs of original inscriptions also housed in Meritt’s collection reveal another layer of scholarly process. On their reverse sides, the photographs bear Meritt’s specific instructions for how the inscriptions should appear when published in the academic journal Hesperia. These handwritten notes directly influenced how ancient artifacts were visually presented to the scholarly world, shaping both interpretation and understanding for the researchers that followed.

Marginalia as Memoir

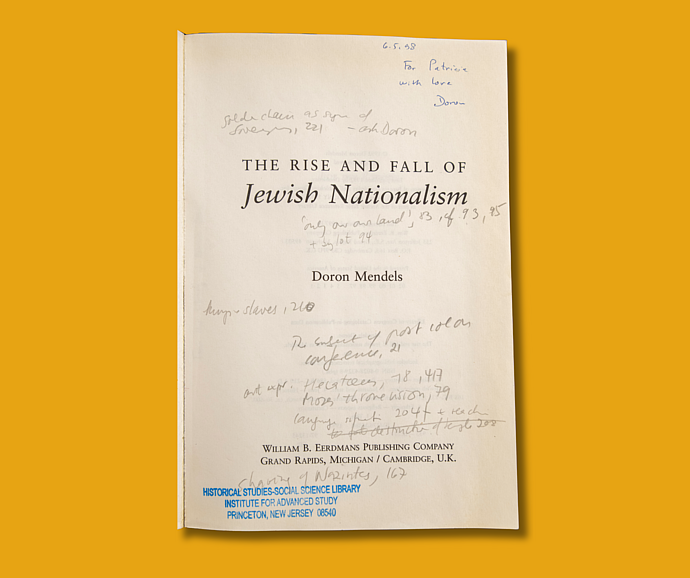

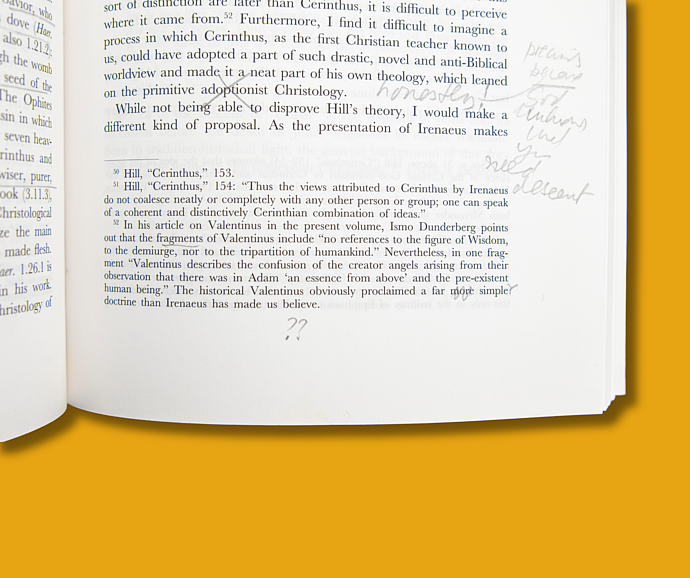

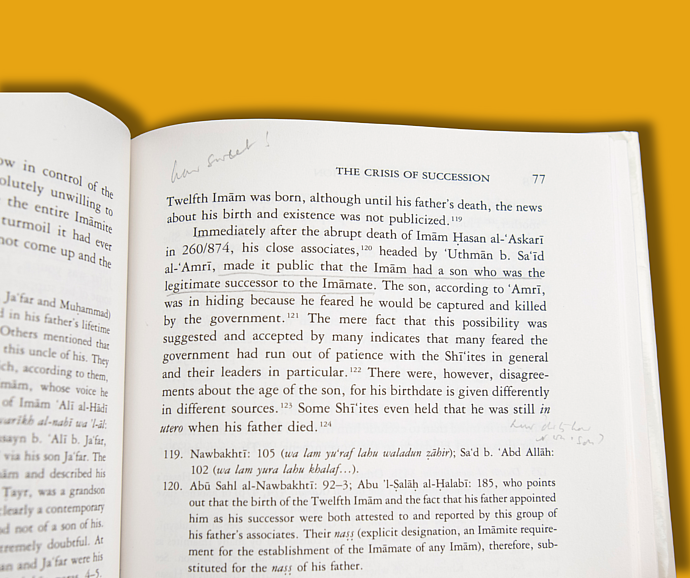

Patricia Crone, Professor (1997–2015) in the School of Historical Studies, had a distinct character that was felt both on campus and in her significant collection of books, many of which she donated to the Historical Studies - Social Science Library. Crone, a foremost scholar in Islamic studies, engaged thoroughly with her texts, leaving many annotations and comments in the margins of works she read. Her scholarship shed light on and challenged existing knowledge about Islamic culture, history, and the Near East.

Her bold personality can be seen in the marginalia of two of her personally owned books, where numerous annotations display Crone’s reactions and critiques of the text. In a declaration of fondness, Crone notes “How sweet!” and, on another page, textually exclaims “Honestly!” Crone was a critical scholar, daring in her work and an active participant in discussion at the Institute, traits that are evident in the marginalia of the texts with which she engaged.

Philosophical Exchanges

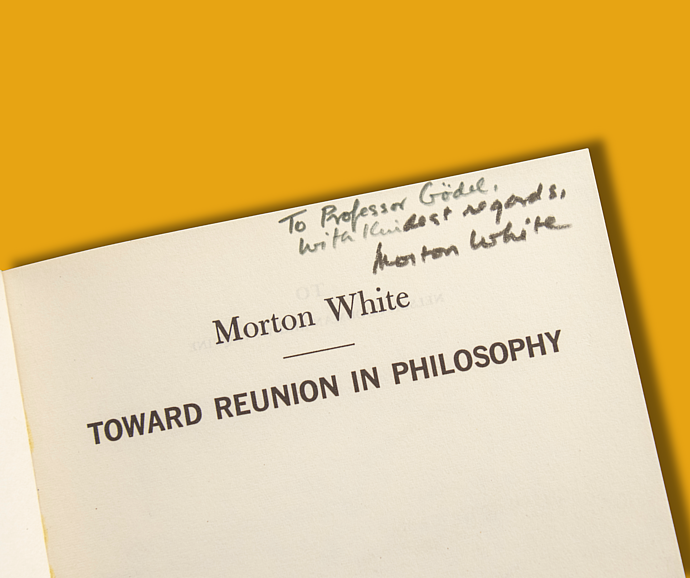

While finding Kurt Gödel’s annotations in mathematical texts is hardly surprising, his engagement with philosophical works offers a glimpse into the interactions between Institute scholars beyond the everyday conversation that one might expect—crossing paths at afternoon tea or sharing knowledge at one of the Institute’s many blackboards. Such is the case with his notes in Morton White’s Toward Reunion in Philosophy, where White—who served on the Faculty of the School of Historical Studies (1970–2016)—personally inscribed the title page to Gödel in pencil.