Embedded Portraits: Appending a New Myth to an Old Myth

Religious art of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance in Europe was marked by the creeping presence of the prosaic, the concrete, the familiar, the everyday. Vivid descriptions of furniture and clothes, local flora and landscapes, hometown buildings and skylines, vignettes of laboring and sporting peasants threatened to distract the devout beholder from the sacred narrative. The purpose of the painting, after all, was to train the mind on the episodes of the lives of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints. A dramatic instance of this profanation of the cult image was the embedded portrait, the topic of my research at the IAS in fall 2011.

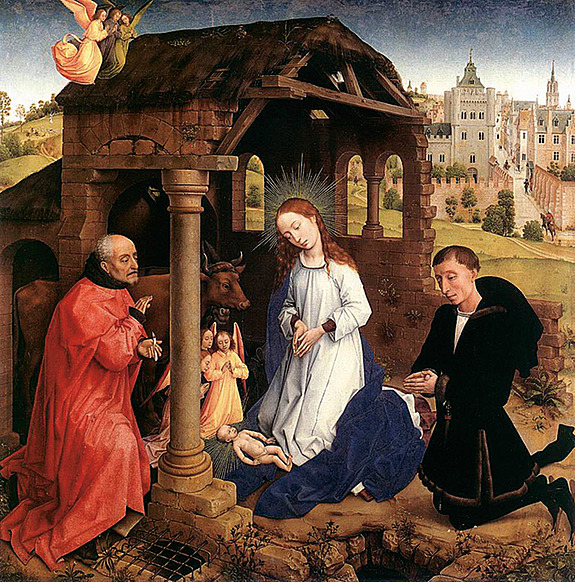

The embedded portrait is the image of a real, modern person, usually the donor or person who paid for the painting, introduced into the narrative. The donor has him- or herself depicted in an attitude of pious attentiveness. A good example is the Nativity of Christ by the Flemish artist Rogier van der Weyden, painted in the middle years of the fifteenth century—the exact date is unknown—and today in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. This is the central section of a three-paneled altarpiece, or triptych, perhaps once mounted on an altar in a chapel, perhaps displayed in an altar-like space in a home. Mary and Joseph, sharing quarters with an ox and an ass, contemplate the naked body of the Child. The stall is pictured as an ancient building in ruins, a symbol of the Jewish and pagan belief systems that Christianity was meant to supersede. The city in the background resembles neither Bethlehem nor Jerusalem but rather, with its spires, gables, and tiled roofs, a modern northern European town. The gentleman at the right, finally, wears an expensive-looking fur-lined coat and wooden clogs to protect his fine pointed shoes. He presses his hands together in reverence. This is the donor. He is not identified by an inscription or a coat of arms. But there is good reason to believe, on the basis of the painting’s whereabouts in the seventeenth century, that he is Pieter Bladelin, a man of respectable origins who rose through political acumen to a high station in the court of the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, in Bruges.

Bladelin is not a diminutive supplement to the sacred painting, pressed into a margin or a corner. He appears in full scale alongside the holy personages. He is not disguised as a historical figure; as one of the Three Magi, for example. The disguised portrait, or cryptoportrait, was a favored tactic of some of Bladelin’s contemporaries. Bladelin is not playing a role; he appears as himself, in his own clothes. He occupies a measurable patch of ground at the site of the Nativity—“real estate” in Bethlehem, as it were. His body casts a shadow. And yet the Virgin and Joseph take no notice of him. Surely we are not meant to believe that if they turned their heads they would see him kneeling there. He is an anachronistic interloper, an invader from another time and space.

Not much is known about Bladelin the man. His patron Philip the Good valued his political judgment and rewarded him with financial responsibility, eventually with the lucrative post of treasurer and governor general of Burgundian state finance. A contemporary chronicler described him as riche de biens de fortune outre mesure, “wealthy beyond measure.” Van der Weyden’s painting is the only image of Bladelin that survives, and it shows a humble Christian immersed in grave reflection on the mystery of the Incarnation and the promise of Redemption. The embedded portrait is a public, or semipublic (we don’t know who had access to the picture), profession of his piety. Did Bladelin believe that the Virgin Mary herself, jealous of her cult, was keeping watch over the shrine and was also impressed by this painted proof of his devotion? It is hard to say.

The painter van der Weyden, subtlest of artists, in his own lifetime the most admired artist in Europe, was no mere servant of the donor Bladelin. He introduces ambiguity into the image by suggesting that the modern man’s participation in the historical event is incomplete, imperfect. Bladelin’s gaze, hands, and knees do not point directly at the Child but rather just to his left. This indirection raises the possibility that the painting represents not the Nativity itself but the donor’s vivid imaginative recreation of the event. Yet the slight overlap of Bladelin’s body and the spreading robes of the Virgin, once we have noticed it, suggests just the opposite, namely, that he is really there. Perhaps it is best to think of the painting not as a stable statement of fact but as a carefully calibrated reflection on the difficulty of communicating with personages doubly remote from our here and now: distant in time, but also distant by virtue of their enviable continuity with the divine source of authority and meaning.

The painting emphasizes Bladelin’s incomplete participation in the scene. The portrait is set like a gem in the midst of the painting. The dense description of the bowed head is radiant. Bladelin’s physiognomy is more memorable than the generic heads of Mary and Joseph. The artificial worlds that the religious imagination builds are unlike the world experienced every day as fact. The painting acknowledges that dissimilarity by staging a clash between two different modes of pictorial signification. On the one hand, there is the Holy Family, the birth-stall, the ox and the ass, and the angels. The picture summons these elements of the myth by quoting other pictures. The painter’s own picture cannot stray too far from established pictorial conventions or its subject will not be recognizable. The beholder must believe that the pictorial tradition supporting this painting is rooted in antiquity and transmits reliable knowledge about the historical Nativity. On the other hand, there is the portrait of Bladelin. That portrait does nothing other than point to something real in the world. Rogier van der Weyden has passively transcribed a patch of reality. Bladelin’s person is a singular fact that almost surely had never before been depicted. The significance of that fact—Bladelin’s unique appearance—is not clear. Why did a sacred image need to record that appearance? The depictions of the Holy Family, derived from tradition, carry with them bundles of associations and meaning. Bladelin’s portrait does nothing other than anchor the painting, and the altar and chapel it adorns, to Bladelin the man.

But the portrait has another significance that emerges only when the way it is linked to the factual world is compared to the way the rest of the picture is linked to reality. The portrait’s strong referential link to the world is achieved by the painter’s dazzling technical skill. The portrait convinces us of its own fidelity to its model even though we don’t have the model to compare it to. Before the fifteenth century in Europe, painting did not have this weapon in its arsenal. Now suddenly the portrait makes the factual world reappear inside paintings. The embedded portrait casts doubt on the factuality of the persons and events described by the rest of the picture. The portrait lands inside the religious painting, the depicted myth, as a foreign body. It is a hard fragment of the real that suggests that everything around it is a mere fiction, a product of a weaker form of signification.

By introducing irreducible fragments of real life, in the form of portraits and other individuated descriptions like the cityscape in the background, the painted image opened its borders to lived experience. For experience, the world is emergent. It is always unfolding in time. Painting has difficulty representing this kind of time. The portrait tries to do that, paradoxically, by representing the individual fixed in historical time. For that individual, and we know this from our own experience, is exposed in every way to the passage of time. The portrait with its hidden reserve of life reveals the characters surrounding it to be mere characters. The real subject of Rogier van der Weyden’s painting is the tension between emergent time and mythic time.

So there are two ways of looking at the painting. We can almost see the painting “flip” as we look at it first one way, then the other. One might choose to see the portrait of Bladelin as a blank, unwelcome dead spot in the scene that contributes nothing to our confidence in the historical reality of the Nativity, and nothing to our understanding of the meaning of the event. From that point of view, the portrait has only a minimal capacity to generate meaning. It is not really a symbol of anything, it just is. It is sub-artistic, in the same way that photography is in some sense sub-artistic. Or one might choose to see the portrait as the living core of the painting, animating a dead Biblical story by throwing it open to human experience and subjectivity. There are two dark apertures in the ground in front of Bladelin, one of them covered by a grill, opening onto a subterranean cavity. That cellar is the prison-house of the satanic energies that Christ will one day subdue through his sacrifice. Is it not also the painting’s metaphor for the recesses of the self—for the unconscious, we would say today—where the conflicts of the mind with itself must be contained for the sake of social life? The image of the donor appends a new myth to the old myth: the powerful modern myth of human subjectivity, with its depths of feeling and self-awareness, as the ultimate source of meaning. The modern devout is no longer the presumptuous intruder at someone else’s event. Now it starts to seem possible that the sacred event is nothing other than the creature of his imagination.