Picasso Harlequin

Two years ago I was asked to organize a medium-size Picasso exhibition in Rome, the first in that city since 1953, that would function as an introduction to the artist’s work for a whole generation of Romans who had not been exposed to it (unless they had traveled, of course). Had I known that I would not be able to borrow anything from the Musée Picasso in Paris because it had rented out its entire collection for several years, or anticipated other frustrations of the same magnitude, I probably would have declined the offer. But what I call the “smell of turpentine” was so strong that I discarded all caution—I find few things as rewarding as being able to bring together several artworks and engineer a dialogue among them. And the intellectual challenge was particularly exciting. It might sound strange, but it is a question one does not think of very often: what is specific to an artist, and how can one summarize his or her achievement? In the case of Picasso, this is quite a conundrum, for the two aspects of his production that are absolutely unique are its quantity and its diversity.

No artist, throughout the entire history of world art, is known to have produced as many works as Picasso—and this without the help of any assistant (as opposed to Rubens’s army of apprentices working for him in his studio, for example). The only time he requested any help was when he wanted to learn a technique (in the late twenties he asked his friend Julio Gonzales how to weld metal, in the early fifties he asked a potter how to work a wheel); as soon as he had mastered the technique in question, he would retreat into the solitude of his studio and, more often than not, find ways to subvert its conventions. If one counts everything, all of his drawings and sketches, one can estimate that Picasso’s output is well above 30,000 works—which is to say that no matter how large an exhibition could be, it would only include a minute proportion of his production.

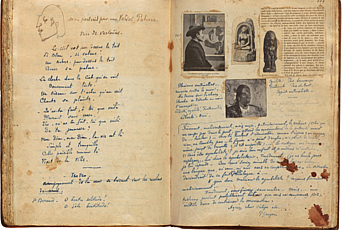

With this in mind, I chose to concentrate on the second unparalleled characteristic of Picasso’s work, its astonishing heterogeneity—which is the main reason I focused on the years 1917–37, the most diverse period of his career. Many artists develop several distinct styles throughout their life, but sequentially, one at a time, moving forward without return—as did Picasso himself at the beginning of his career (his Blue Period was followed by a Rose Period, then Cubism, itself divided into several chronological phases). But starting timidly in 1915–16 and then in full force during his sojourn in Rome, in February through May 1917, Picasso developed a new attitude that would remain an essential feature of his aesthetics. From then on, he would never abandon anything; he would always invent new styles but no longer discard old ones. Perhaps under the spell of the classical monuments and sculptures of antique Rome, or the paintings he saw in Pompei and Naples, Picasso discarded any idea of “evolution” and “progress.” Over the years he would build a phenomenal arsenal of forms and approaches, and feel free to summon any one of them any time he wished, any time he saw fit.

There is an obvious playfulness in the way Picasso constantly shifted his artistic identity when least expected—and the title of the show, “Picasso Harlequin,” was meant to reflect that: he was like Harlequin, a character with whom he identified all his life and of whom he drew and painted many versions in various, often incompatible, styles. Like Harlequin, he could become anything he wanted, put on any mask, take out any card from his sleeve. He could be several artists at once. Thus on the same day or week or month, he could offer a cubist, a neoclassical and a surrealist version of the same subject, for example, and he would relish in such clashes of incompatible manners. The hundred etchings of the Suite Vollard, which were included in the show, provide a perfect case in point (most of the plates are dated, so it is particularly easy to observe the rapidity of his identity switches). To signal that this distinctive aspect of Picasso’s work was the topic of the show, I placed at its very entrance two paintings that have only in common the fact that they are his, even though they were made just a few months apart—the cubist Italian Woman, painted in Rome in April through May 1917, and the neo-classical Harlequin, painted in Barcelona in the early fall of that year (to drive the point home I could have found works that are strictly contemporary, but they would not have matched the sheer force of those two towering sentinels).

Picasso was obviously proud of his work’s multifariousness. However, this should not be confused with fickleness. He liked to work in series, often staying with the same topic for months in a row, and sometimes returning years later to a series that he felt had not yielded all it could. Picasso’s visual memory is indeed spectacular. The Woman in a Hat that Picasso painted in July 1934, for example, is directly reminiscent of sketches he made in the fall and winter of 1912–13; the Head of a Horse he painted in 1937 as a study for Guernica seems to derive from a sketchbook he filled in fall 1917 while resting in Barcelona from his exhausting work in Rome for the ballet Parade. Unlike Harlequin, Picasso had a very long attention span, and he was anything but lazy. These are the only two major differences in their character, not enough to renounce the metaphor of Harlequin’s tricks and costume for Picasso’s prodigiously varied production.