The Ezekiel Papyrus: Fortune and Misfortune of an Exceptional Manuscript

This summer we had the joy of curating an exhibit at the National Library of Spain in Madrid, titled El papiro de Ezequiel. La historia del códice P967 (The Ezekiel Papyrus: History of the codex P967). The exhibition revolved around a gem of the world’s written heritage, the Ezekiel Papyrus, technically known as codex P967, following Rahlfs’ catalog of biblical manuscripts. We prefer its more descriptive name, which highlights both its material—papyrus—and one of the biblical texts it preserves: the prophecies of Ezekiel.

This extraordinary papyrus codex, whose pages are now dispersed across Princeton, Dublin, Cologne, Barcelona, and Madrid, offers a rare window into the production and circulation of biblical texts and translations in Roman Egypt.

In the following lines, we will undertake a journey that aims to bring you closer, through this unique object, to the production and circulation of the texts and translations of the Bible in Roman Egypt, and to the particular characteristics of the books that contained the sacred text of Jews and Christians. We will focus on the importance of this manuscript for biblical and philological studies, but also for codicological studies, that is, for the history of ancient books.

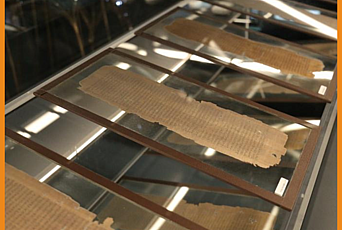

Moreover, we will engage with the history of this magnificent specimen, forgotten or deposited in an Egyptian tomb, buried by the sands of the desert and rediscovered in the early twentieth century. Subsequently torn apart by antique dealers, it was sold piecemeal to collectors from around the world. Due to this unfortunate operation, the book lost its ancient form and was scattered. However, thanks to new technologies and the collaborative work of the various institutions that preserve its pages, we have been able to endow it with a new life in the form of a virtual codex.

Papyrus as writing material

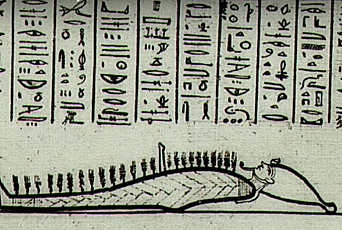

In the ancient Mediterranean world, the accumulation of written knowledge was made possible by a paper-like material crafted from the papyrus plant (Cyperus papyrus), which grew abundantly along the Nile. Used in Egypt since at least the third millennium B.C.E., papyrus served not only for writing but also for making all kind of objects, such as mats, ropes, sandals, baskets, and even boats.

The finest and smoothest fibers from the core of its trunk were selected to manufacture papyrus sheets, which became the most widely used writing material in the ancient Mediterranean, an essential vehicle for the copying and transmission of knowledge and, of course, also for the formation of bureaucracies.

The first papyrus books took the form of scrolls (volumina), named from the Latin verb volvo, “to roll,” from which the English ‘volume’ is derived. The texts were arranged horizontally along the scroll in successive columns. Books written in this format were kept rolled up and could have a titulus, that is, a small strip of papyrus or parchment that hung from the scroll like a label and on which the title or author of the book was written to identify it on the shelf. To open and close the rolls, the reader could use an umbilicus, a cylindrical piece of wood in which the papyrus was wrapped, providing greater stability when rolling and unrolling the book. This book format was used throughout much of antiquity, until the early centuries of our era, when it was gradually replaced by the book format with which we are more familiar today, the codex.

The earliest surviving codices were made of wood—hence the Latin term codex/caudex, referred to the wood from which it was made. Several wooden or waxed tablets were bound along one edge to form notebooks used in schools and legal settings. Adapting this format to softer materials like papyrus gave rise to the modern book. Finds such as the Ezekiel Papyrus—a large-format codex with distinctive features—allow us to trace the early stages of this evolution in bookmaking.

The first papyrus codices were created by stacking sheets, folding them in half to form a quire or fascicle, and stitching the fold with thread and leather reinforcements. This structure was optimized to form codices composed of several quires, which were sewn together to form a complete book, often protected by wooden or leather covers.

The transition from papyrus rolls to codices coincided with the spread of Christianity in Egypt, long thought to be connected phenomena. However, research now has demonstrated this was coincidental: the codex was a Roman innovation that Christians later adopted and popularized.

Examples of biblical texts copied in codex format appear before the fourth century, as seen in the Ezekiel Papyrus—remarkable both for its preservation and for being an early witness to this new book format.

The Ezekiel Papyrus: Characteristics and Contents

Of its original 236 pages, only 200—some of them fragments—survive today. The codex was made by 59 papyrus bifolia—large sheets folded and sewn down the middle, typical of early bindings. Its size, 34 × 12 cm, is unusually tall and narrow compared to the more common 30 × 15 cm proportions. The unusual dimensions make this codex especially interesting. It shows how the early production was still testing the most adequate sizes. And the structure, in one single fascicle, also explains its decay through the centuries.

The preserved part of the codex contains the Greek text of the biblical books of Ezekiel, Daniel (including Bel and the Dragon, and Susanna), and Esther. Because the outer bifolia, more exposed to wear and damage, are missing, Ezekiel begins at chapter eleven and Esther is lost after chapter eight. The Book of Ruth, which likely followed, has not survived. This part may have disappeared in antiquity or later, during the manuscript’s trade and handling by merchants. If additional fragments are ever found in the future, they will likely be small pieces rather than complete folios like those preserved from the codex’s interior. Nothing remains of the original binding, though it was probably a leather case similar to those of the Nag Hammadi codices.

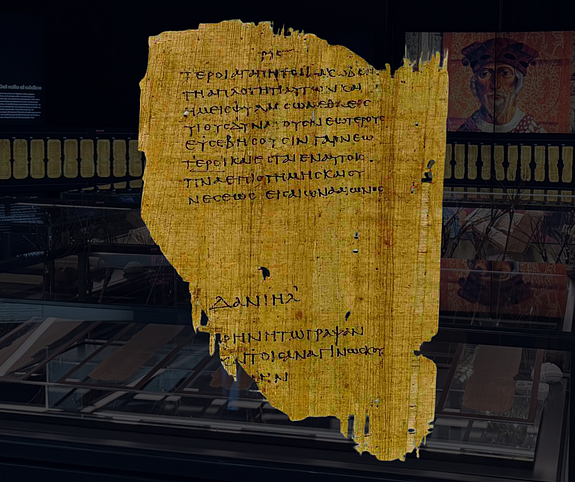

The codex has generous margins and a consistent layout that reflects the care of professional scribes. Two scribes with similar background or training were responsible for the copy: the first copied Ezekiel, and the second completed the remaining books. Their work reveals distinct habits, which led to the differentiation of two separate scribes—Scribe I compressed his or her text, writing up to 57 lines per page, likely to ensure space for the rest of the manuscript, while Scribe II adopted wider spacing of 40–48 lines per page, once that constraint was removed.

The scribes also used several conventions typical of ancient manuscripts. Each page was numbered in Greek numerals at the center of the top margin. The use of nomina sacra—abbreviations of sacred names such as God, Lord, or Holy Spirit, marked with a supralinear stroke—is frequent. Titles appear centered at the end of each book; in Ezekiel, this conclusion is emphasized with a fork-shaped paragraph mark and a coronis, a decorative flourish typical in ancient literary works.

The First Translations of the Bible

The Greek text preserved in the Ezekiel Papyrus makes it an important source for biblical studies. It is one of the most ancient and substantial papyri containing the Septuagint, the earliest Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures.

According to tradition, the Septuagint originated in third-century B.C.E. Alexandria, when Ptolemy II sought to make the Library of Alexandria the center of Mediterranean knowledge by gathering all written works and translating them into Greek. The Letter of Aristeas, dated to the second century B.C.E., recounts that seventy-two Jewish scholars came to Alexandria to translate the Torah—or Pentateuch—into Greek and they accomplished the task in seventy-two days, producing an inspired and perfect version for the Jewish community of Alexandria. Later, other biblical books were translated and the entire corpus became known as the Septuagint (“seventy,” from the Latin septuaginta) in honor of these scholars. Linguistic evidence, however, reveals that the translators were local Alexandrian scholars, as shown by the dialect of the Greek used.

Although the Septuagint was regarded as a sacred and immutable text, disagreement soon arose over its style and accuracy. Some revisions sought a more fluent Greek, while others pursued literal fidelity to the Hebrew original. By the second century C.E., several new versions appeared: Aquila of Sinope’s extremely literal translation, and the smoother, more idiomatic works of Symmachus and Theodotion. Despite these alternatives, many—including Irenaeus of Lyon in Against Heresies—continued to defend the divine inspiration of the Septuagint, noting that it was also the version used by the first followers of Jesus to spread the new faith.

The coexistence of multiple Greek translations in the second and third centuries created great textual confusion. To address this, the scholar Origen compiled the Hexapla, a monumental work that compared the main Greek versions of the Bible with the Hebrew text. He arranged them in six columns (thus the meaning of “hexapla”): the Hebrew text, its transcription in Greek letters, and the versions of Aquila, Symmachus, the Septuagint, and Theodotion.

In the Greek Vulgate, the Book of Daniel eventually adopted Theodotion’s version, replacing the older Septuagint text because it was closer to the Hebrew. Our codex, however, preserves the original Septuagint version, making it a crucial witness for the textual history of the Bible.

Purchase History

One of the interesting issues connected to this manuscript is that it exemplifies the dismemberment and dispersion of antiquities that took place during the twentieth century. It is not an isolated example, but it helps us to understand the paths that the fragments of antiquity took, and eventually to reconstruct them.

The dispersion of our manuscript can be traced through the commercialization of its fragments in the early twentieth century. Although its exact discovery site is unknown—since local finders rarely revealed locations and their excavations were often clandestine—it was likely found in a tomb at the Mir necropolis near Asiut. Pharaonic tombs in this region, carved into the mountains, had long served as dwellings for monks, shepherds, and bandits alike.

The papyrus codex passed through several hands before reaching Shaker Farag el Assiouti (active 1929–36), an antiquities dealer from Asiut who later worked in Beni Suef and probably Cairo. He offered the manuscript for sale, though never in its entirety. In fact, the Italian papyrologist Medea Norsa attempted to acquire it for the Vatican, which only purchased complete manuscripts, but the dealer refused to provide details.

The first fragments sold went to Sir Alfred Chester Beatty (1875–1968), a New York-born mining engineer of Irish descent who became a prominent manuscript collector. After visiting Egypt in 1914, he began acquiring papyri from Cairo dealers and eventually built a major collection of biblical manuscripts. In 1950, he moved to Dublin, where his holdings became the foundation of the Chester Beatty Library. Chester Beatty acquired bifolia from the outermost part of the book—containing text from both the beginning (Ezekiel) and the end (Esther). He also acquired the outermost part of the codex, the most damaged, which was probably already loose.

Shortly after Chester Beatty’s purchase, the Scheide family acquired twenty folios of the Ezekiel Papyrus, adding them to their renowned collection of rare books and manuscripts built over three generations, by William T., John H., and William H. Scheide. In 2015, the grandson, William H. Scheide, a Princeton graduate (Class of 1936), donated the entire library to Princeton University.

Correspondence between John and William H. Scheide, preserved in Princeton’s Firestone Library, reveals the 1935 negotiations for acquiring the Ezekiel pages. Though still a university student, William demonstrated remarkable expertise in his papyrological assessments shared with his father. By that time, the Scheides recognized the similarities with the fragments purchased by Chester Beatty, confirming they came from the same codex. Through David Askren (1875–1939), an American medical missionary in Medinet el Fayum, they purchased the folios in 1935 from Shaker Farag.

The Abbey of Montserrat preserves the papyrus collection of Father Ramón Roca-Puig (1906–2001), priest, papyrologist, and Hellenist, assembled between 1945 and 1970 with the support of patrons and donors. Upon his death, Roca-Puig bequeathed his collection to the Abbey, where it remains for study and conservation. Although details of his acquisition of the Ezekiel fragments are unknown, it likely occurred in Cairo in the 1950s.

The Cologne Papyrus Collection is, together with the Heidelberg and Berlin collections, one of the most important papyrus collections in Germany. It was formed in the 1950s through purchases from antique dealers and private collectors, as this institution never conducted an archaeological excavation in Egypt with the aim of finding papyri. The collection was founded by Joseph Kroll, director of the academy, and Reinhold Merkelbach, a classical philologist specializing in the study of Greek classics and religion. As for the purchase of the pages from the Ezekiel codex, they were acquired in Cairo in the spring of 1956 from a bookseller named Feldmann.

The papyrological collection of the Fundación Pastor de Estudios Clásicos in Madrid originated from a generous donation by Pénélope Photiadès, who gifted part of her private collection to Spanish Hellenist and professor Manuel Fernández Galiano around 1961. She was a Swiss scholar, resident in Geneva where she collaborated with Victor Martin on the Bodmer papyrus. Little is known about how and when Penelope Photiadès acquired her papyrus collection. In her editions and articles, she simply states that they come from “Ben Hasan” (sic). From some documents in her archives, we suppose that some of her papyri must have been acquired through the Cairo merchant Mohammed Abdel Rahim el Shaer, who also sold papyri to the University of Cologne in 1953 and from whom Ramón Roca-Puig purchased papyri in 1959, according to notes preserved in the Abbey of Montserrat.

After the donation, the papyri were housed at the Fundación Pastor, though the Ezekiel codex pages were transferred to the National Library of Spain in 1983 for optimal conservation due to their exceptional value. These are the fragments were exhibited at the National Library as part of the El papiro de Ezequiel. La historia del códice P967 exhibition from May 8 to November 15, 2025.

The Papyrus Today

In order to provide some kind of reparation to the—most probably illegal—dismemberment of this manuscript, the work of papyrologists and biblical scholars has identified its fragments and performed philological restorative surgery. The new technologies of imaging have provided the perfect platform for virtually reuniting the pieces of this centuries-old puzzle. Moreover, exploring the documents which attest to the purchase of the different parts provides transparency to the transactions. The life and fortunes of this remarkable manuscript exemplify how the antiquities market—driven above all by economic interests—has often compromised the original integrity of the artifacts, preventing their study and leading to the loss of much of the information needed to reconstruct their history. Yet, thanks to the combined efforts of the institutions devoted to its preservation and of scholars approaching this heritage from diverse scientific perspectives, it is still possible to recover a wealth of knowledge that deepens our understanding of the transmission of the Greek biblical text in the early centuries of the first millennium, and denounces a market that not always acted ethically. In honor of this exhibit, the Spanish National Library will provide an online facsimile version of the Ezekiel Papyrus.