World Views

A scientific analysis of the world can give a very accurate account of the play of matter and energy that we witness around us, but it does so from a purely objective point of view. It is not clear whether such an account covers all basis. Certainly it doesn't do so at present. Will a future science be able to give a full account of consciousness? And if it can do so, will that mean that subjective experience can somehow be reduced to a particular form of objectivity?

We do not know the answers to those questions. And as long as we don't know, it is wise to explore what type of alternatives there are to purely scientific world views. Are there other ways that are equally convincing as the scientific approach? Many scientists reject non-scientific views of the world as based mostly on speculation or tradition or wishful thinking. This, however, may be based more on a lack of familiarity than anything else. If the only access we had to science would be through popular descriptions, science would be a lot less convincing too.

The problem is that it takes time, quite a lot of time, to probe into a different world view to the extent that one can begin to get a feeling of what it is all about. To get that feeling for science, it takes at least a few years of undergraduate studies, and a few years of grad school, where you start doing original research, would be much better. And all of that follows familiarity and training through what one has earlier heard in high school and before. In contrast to all the hours that we are exposed to information about science, we normally receive hardly any in-depth information about philosophical systems or non-western world views. No wonder that a comparison seems so difficult to make.

Science, Phenomenology, and Dzog Chen

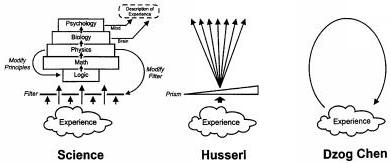

I have spent a significant fraction of my time over many years delving in to two other world views besides science, the field of my main professional training. The first area is phenomenology, the school of philosophy that originated with Husserl, in the beginning of the twentieth century. When reading Husserl, I was struck by his respect for experiential methods. Like an experimental physicist working in a laboratory, he saw the whole world as a lab. Husserl approached all phenomena around him as offering him insight about the structure of the consciousness in which those phenomena were present. And he designed specific experimental guide lines for how to conduct philosophical experiments and analyse their results.

I have spent a significant fraction of my time over many years delving in to two other world views besides science, the field of my main professional training. The first area is phenomenology, the school of philosophy that originated with Husserl, in the beginning of the twentieth century. When reading Husserl, I was struck by his respect for experiential methods. Like an experimental physicist working in a laboratory, he saw the whole world as a lab. Husserl approached all phenomena around him as offering him insight about the structure of the consciousness in which those phenomena were present. And he designed specific experimental guide lines for how to conduct philosophical experiments and analyse their results.

The other area I studied in detail is a bit more difficult to characterize. The closest pointer I can give is to mention dzog chen, a system of philosophical and spiritual training in Tibet, shared by both Buddhists and practitioners of the older Bon tradition. Briefly, dzog chen views all phenomena around and in us in the aspects in which they arise, without being distracted by the labels and identifications they constantly carry for us. An interesting and inspiring new approach to a somewhat similar world view (although not related to dzog chen in any formal way), was published a few decades ago in the book Time, Space, and Knowledge (1978; Berkeley: Dharma Publ.) by Tarthang Tulku. I find it the single most interesting book I have ever read. It provides a framework wide enough to accomodate other world views, yet with an inner logic and consistency that make it a practical guide for further explorations, theoretically as well as experientially.

The other area I studied in detail is a bit more difficult to characterize. The closest pointer I can give is to mention dzog chen, a system of philosophical and spiritual training in Tibet, shared by both Buddhists and practitioners of the older Bon tradition. Briefly, dzog chen views all phenomena around and in us in the aspects in which they arise, without being distracted by the labels and identifications they constantly carry for us. An interesting and inspiring new approach to a somewhat similar world view (although not related to dzog chen in any formal way), was published a few decades ago in the book Time, Space, and Knowledge (1978; Berkeley: Dharma Publ.) by Tarthang Tulku. I find it the single most interesting book I have ever read. It provides a framework wide enough to accomodate other world views, yet with an inner logic and consistency that make it a practical guide for further explorations, theoretically as well as experientially.

My first attempt to summarize my understanding of these three world views that I have studied was when I was invited to give a plenary talk at the third Tucson conference titled Toward a Science of Consciousness where I gave the paper:

- Exploring Actuality through Experiment and Experience, by Hut, P., 1999, in Toward a Science of Consciousness III, eds. S.R. Hameroff, A.W. Kaszniak, and D.J. Chalmers (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press), pp. 391-405 (available also in postscript version).

A more brief summary can be found in the presentation

A more brief summary can be found in the presentation

that I gave in 2000 as a position paper, when I was asked to give the closing talk at the Future Visions conference in New York City, in September 2000, as part of the meeting of the State of the World Forum in tandem with the United Nations Millennium Summit.

An even more brief summary of my thoughts in this area is presented in

in response to an invitation in the year 2000 to write a contribution to the The World Question Center

I published a related view on the same web site in 2006, in an equally brief piece on

Another piece on the same web site, from 2007, discusses the freedom that scientists have in changing not only their goals, but even their methods:

And yet another piece, from 2008, discusses the limitations of approximate explanations:

What Else is True

|

Another short summary of my views can be found the manifesto What else is true?, an introduction to the orientation of the Kira Institute, which I wrote with my colleagues Roger Shepard, Steven Tainer, Bas van Fraassen, and Arthur Zajonc. Starting from a scientific world view we note that there seems to be pieces missing, hence our question.

We published a general introduction to some of our ideas in the paper An even more brief summary of my thoughts in this area is presented in

- Elements of Reality: A Dialogue, by Hut, P. & van Fraassen, B. 1997, J. of Consc. Stud.4, No. 2, 167-180 (available also in postscript version)

We choose the form of a dialogue, since it was the result of a number of discussions we had in Princeton in various cafes when we happened to meet each other, intentionally or by accident. The main questions we kept coming back to were notions such as value, beauty, or meaning - or more down to earth: anger, fear, joy, color, smell, and other `secondary' qualities whose reduction to scientific qualities seems today as difficult as it ever was.

Here is an interview with me, in the magazine The World & I, in the August issue of 2001, titled What else is true?

Here is an interview with me, in the magazine The World & I, in the August issue of 2001, titled What else is true?

Pluralism

The first presentation I gave on world views was triggered by my participation in a seminar on science studies, organized by my colleague Clifford Geertz at the Institute for Advanced Study during the academic year 1992-1993. In attending that seminar, I found myself playing three roles simultaneously, that of object, subject, and meta-subject, if you want. I was the object of study, a representative native, so to speak, as a working astrophysicist. In looking over the shoulders of the science watchers, I played the role of fellow watcher. And, reflecting upon the whole process, I also played the indirect role of watching the watchers. Toward the end of the seminar series I gave a talk on that topic at one of the Thursday lunch seminars in the School of Social Sciences, at the Institute for Advanced Study, titled

I presented a much shorter argument for plurality almost ten years later in:

in response to an invitation to discuss the relation between science and the humanities in the Reality Club, on the edge web site.

Here are three very different views, presented by three physicists, as the outcome of a series of lunch conversations at the Institute for Advanced Study. They nicely show how wide the range of interpretations of science can be, even among practitioners how agree upon the same rules for conducting science:

- On Math, Matter, and Mind, by Hut, P., Alford, M. & Tegmark, M., 2006, Foundations of Physicsxx, xxx-xxx. (available also in preprint form as physics/0510188 ).

Here is a short piece, in which I answer the question What inspired you to take up science?

- Traveling to the Edge of the Known, by Hut, P., 2006, invited contribution to the spiked web site.