At a meeting of the Institute Faculty held on November 2, 1966, Carl Kaysen, IAS Director (1966–76), announced his idea for a program in the new School of Social Science. He explained that the program would focus on “what might best be described as organization, communication, and decision.” This area of study, he said, would be an interdisciplinary field in which “the work of sociologists, political scientists, economists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, linguists, and students of the logic of computing, all converged.”1 Kaysen did not yet have a name for this new area of study, but today we know it as “cognitive science” and we refer to its beginnings as the “cognitive revolution.”

In the cognitive revolution, psychologists, recognizing that developments in information processing had potential for studying the human mind, sought for the first time to apply new ideas in early artificial intelligence, computer science, and neuroscience to psychology. The Institute, as the home of one of the first modern computers, was uniquely poised to serve as an early hub for this nascent field of study. The Institute’s tenure as a gathering place for cognitive scientists would ultimately prove short-lived, yet the program Kaysen began in the School of Social Science represents a milestone in the Institute’s history, a significant early attempt to venture into a new and still undefined area of research. Records in the Institute’s Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center offer a glimpse at this bold effort, decades in the making.

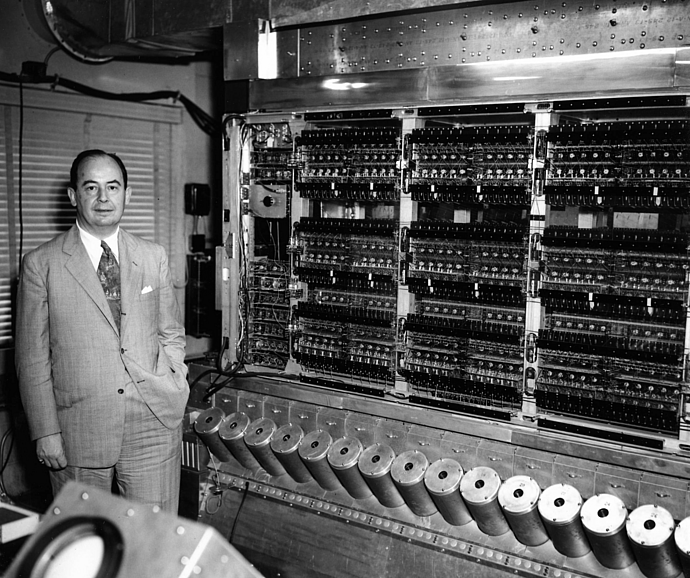

In May 1946, twenty years prior to Kaysen’s announcement, several of the Institute’s early scholars attended the first in a series of interdisciplinary conferences focused on applying tools from the physical sciences and mathematics to the biological and social sciences. For eight years, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation hosted this series of conferences, now known as the Macy Conferences, in New York City and Princeton. The conferences included John von Neumann, Professor (1933–55) in the School of Mathematics and head of the Electronic Computer Project (1946–55); Claude Shannon, Member (1940–41) in the School; and Julian Bigelow, who served as a Member from 1946–2003 across the Electronic Computer Project and the Schools of Mathematics and Natural Sciences. They worked alongside Princeton University Professor Oskar Morgenstern and significant social scientists such as Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. For nearly a decade, the conferences placed Institute community members at the forefront of efforts to apply information theory and computing to human and social sciences.

Meanwhile, IAS Director (1947–66) J. Robert Oppenheimer laid the groundwork for a program that would bring this work to the Institute. Seeking to broaden the kinds of research being conducted at the Institute, Oppenheimer asked the Board of Trustees in 1947 for a special fund that would offer “opportunity for exploring new fields outside and beyond the specific areas of the schools.” The Board granted Oppenheimer a Director’s Fund to bring in individuals working in disciplines outside of the established Schools of the Institute.2 They included a host of distinguished scholars, including important literary theorists and writers, like T. S. Eliot, and distinguished biologists, like George Wald. Anticipating an opportunity on the horizon for fruitful new work in psychology, Oppenheimer also began to explore the idea of using the fund to invite psychologists.

Oppenheimer first expressed an interest in psychology, and particularly in the new efforts to use quantitative methods in psychology, in a planned address for the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1948. Though Oppenheimer never actually delivered the proposed lecture due to scheduling conflicts, he wrote to the APA President Donald Marquis that he had “hoped in particular to stress some of the important analogies between the work in physics and the work in psychology.”3

By November 1949, Oppenheimer would use the new Director’s Fund to invest in an exploratory psychology conference at the Institute. Jerome Bruner, a pioneer in cognitive science who would become a co-founder with George Miller of the Center for Cognitive Studies at Harvard in 1960, was invited, as well as a group of other eminent scholars: Frank A. Beach, Edwin Boring, Dorwin Cartwright, Ernest Hilgard, David M. Levy, Donald Marquis, Helen Peak, Robert Richardson Sears, David Shakow, Edward C. Tolman, and Dael Wolfle. Jerome Bruner reported in his notes that the conference served “to assess the kinds of theoretical inquiry which might be fruitfully undertaken by a smaller working team of psychologists at the Institute.”4

Identifying the areas of inquiry that seemed suitable to psychologists at the Institute was more difficult than Oppenheimer had hoped, however. And, more widely, determining the direction and goals for the new interdisciplinary field as a whole proved a formidable challenge. Later, in a 1950 letter to Oppenheimer, Jerome Bruner reflected on the conference: “Our week in Princeton served well in showing that there is no such clear-cut objective to be sought. The field of psychology is not highly enough developed to be able to name in advance its most promising objective with any hope of being able to reach that objective, or even to sketch it with clarity in advance.”5 Based on what Oppenheimer observed at the 1949 conference, he decided against establishing a full-fledged psychology program at the Institute.

Apparently still believing that promising work lay ahead for psychology, however, Oppenheimer began to fund individual scholars working in the field of psychology who might benefit from time at the Institute. The first of these psychologists began to arrive in 1950, including George Miller, Member (1950–51) in the School of Mathematics, an early contributor to the field of psycholinguistics; Jerome Bruner, Member (1951–52) in the School; and David M. Levy, also Member (1951–53) in the School, an innovator in child psychology.

These first scholars opened the door for others. In May 1952, Oppenheimer sent a letter of invitation to the psychologists Boring, Bruner, Miller, and Tolman, as well as Paul Meehl and Ruth Tolman. In the letter, Oppenheimer invited the addressees to serve on an advisory panel that would consult on “instances in which membership in the Institute would be of benefit to scientific progress in psychology.”6 This advisory panel consulted with Oppenheimer throughout the 1950s. In that decade, the Institute hosted about a dozen eminent scholars in psychology, including Jean Piaget, Member (1954) in the School of Mathematics, and Noam Chomsky, Member (1958–59) in the School, another founder of the field of cognitive psychology.

For reasons that remain undocumented, the Institute and Oppenheimer ceased such targeted efforts in 1961. Yet Carl Kaysen, within months of stepping into the role of Director in 1966, redoubled Oppenheimer’s earlier efforts. In a press release dated June 19, 1967, the Institute announced the beginning of a three-year experimental pilot “Program in Social Science,” which would run from 1968 to 1971.7 This program would include scholars working on “organization, communication, and decision.”

The new program represented the most robust effort yet to provide a home for scholars working in cognitive science. In the spring of 1968, Kaysen extended a formal offer of the position of Visiting Professor to R. Duncan Luce, a preeminent scholar in mathematical psychology. Kaysen proposed that Luce would explore the “theoretical aspects of the study of organization, communication and decision in both social organizations and in the functioning of the individual” and would be “invited to take the lead in shaping this part of the program.”8 Kaysen turned to George Miller as a second senior scholar to lead the program, and Miller returned to the Institute as a Member (1970–72) and Visitor (1972–76), first in the Program in Social Science and then the School of Social Science.

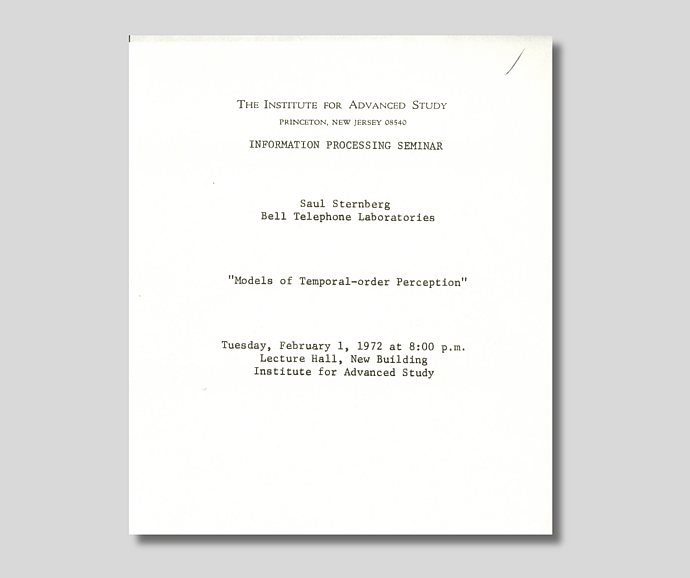

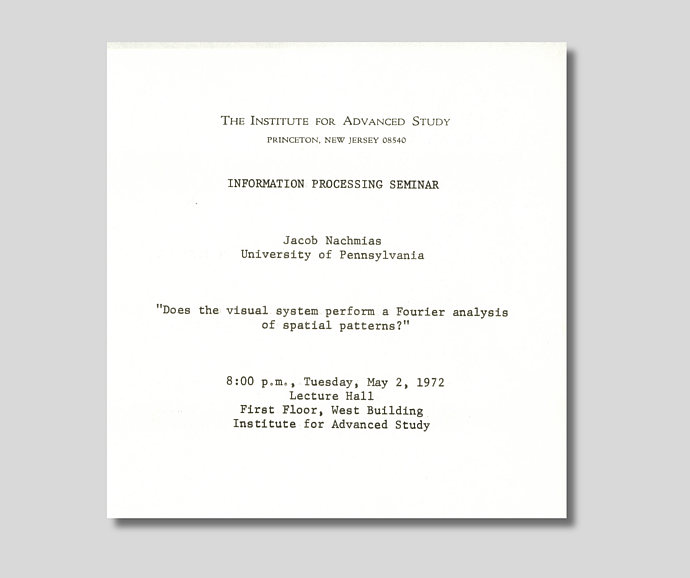

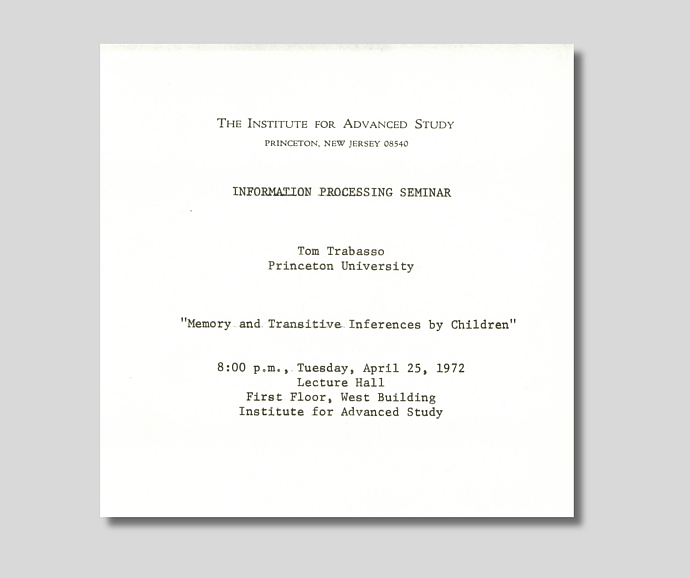

The 1970–71 and 1971–72 academic years saw the peak of the Institute’s involvement in the cognitive revolution. Kaysen first hosted a conference in the fall of 1970, which aimed “to collect views from various eminences as to what the school might do.” Participants included several cognitive scientists, with Luce and Miller foremost among them.9 From 1970–72, Luce organized regular seminars on topics in cognitive science, inviting participants from Bell Telephone Laboratories, the Educational Testing Service, Princeton University, Rutgers University, and the University of Pennsylvania. These seminars offered occasions for cognitive scientists to gather and collaborate.10

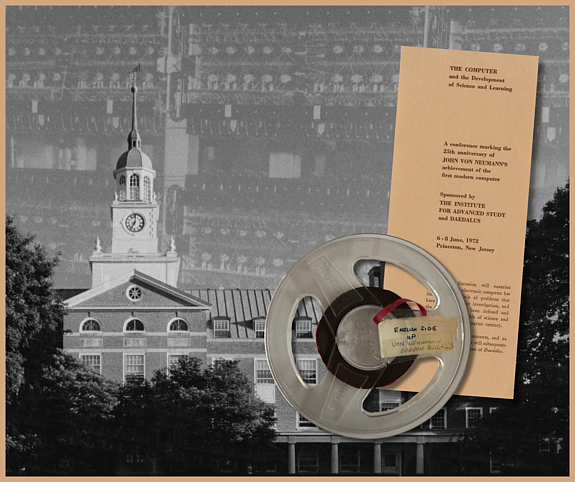

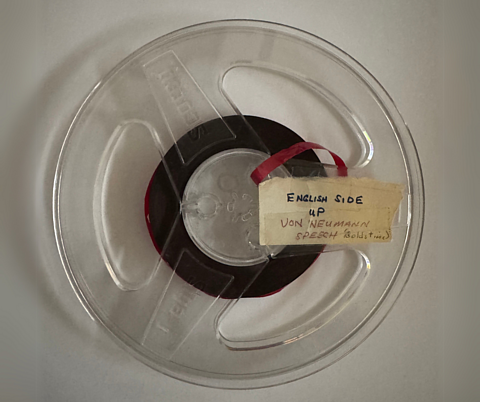

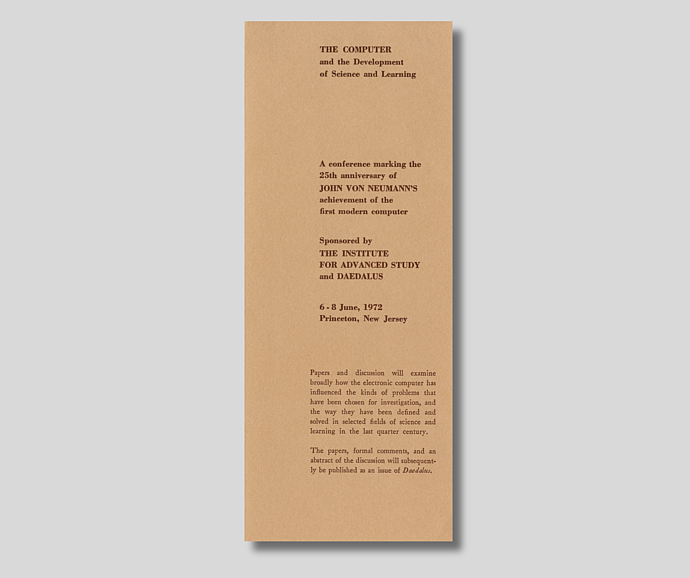

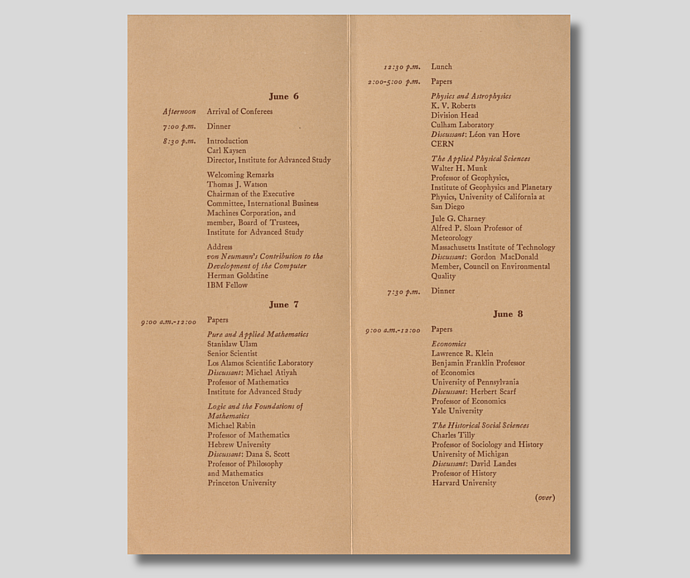

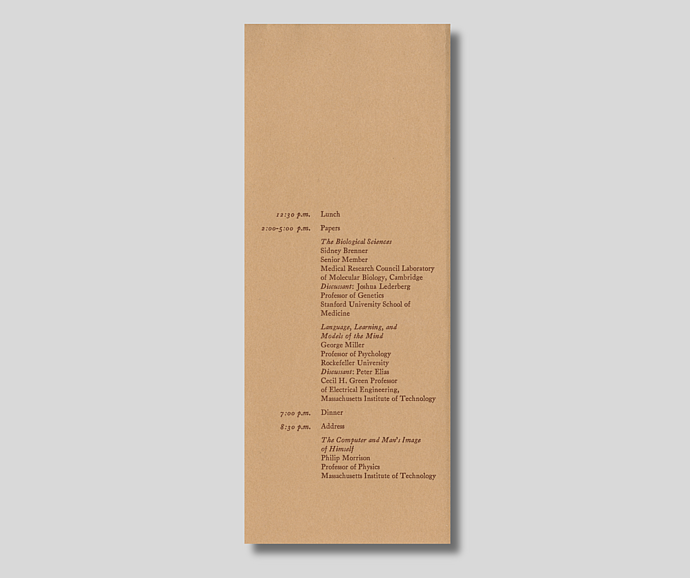

In June of 1972, the Institute hosted yet another important conference. It commemorated the 25th anniversary of the first modern computer, developed by John von Neumann. The speakers at the conference came from diverse areas of study, including pure and applied mathematics, logic and the foundation of mathematics, physics and astrophysics, applied physical sciences, economics, historical social sciences, biological sciences, and what was termed “language, learning, and models of the mind.” In this final area of study, George Miller was the invited speaker.

Miller’s lecture offered insightful reflection on the state of the cognitive revolution in the early 1970s as well as a succinct summary of how the computer had fundamentally altered the field of psychology over the past several decades. According to Miller, the most influential effect of the computer in his field had been what he called “the computer metaphor,” specifically, the idea that “men and computers are merely two different species of a more abstract genus called ‘information processing systems.’” Thus, von Neumann’s theoretical work had contributed to a new metaphor for understanding of the mind.11 In The Computer and the Brain, von Neumann wrote, “The human brain is, after all, the best example we have of an intelligent system … we can use these biologically inspired paradigms to build more intelligent machines.” In Miller’s address, he argued reciprocally that the computationally inspired paradigm of the machine could be used to better understand the human mind.

By the mid 1970s, the Institute’s governing bodies agreed that it could no longer serve as a hub for the field of cognitive science. Under the influence of Clifford Geertz, Professor (1970–2006) in the School of Social Science, the School became an increasingly significant center for anthropological and sociological studies. Nonetheless, the Institute’s efforts to foster the new field of cognitive science represent an important chapter in its history of sponsoring innovative, trailblazing research. The connections that George Miller drew between von Neumann’s work and the work of later cognitive scientists like himself highlight the Institute’s role in the development of modern computing, and how its unique approach to discovery positioned it to participate in the cognitive revolution. Recognizing its standing strengths but also seeking to expand its reach, the Institute sprang on the opportunity to venture into a new area of study and, in the process, played an important role in the birth of cognitive science.

[1] Faculty Meeting, November 2, 1966, Draft Minutes. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. School records: Development of School of Social Science, 1966–1969

[2] Special Meeting of the Board of Trustees of the Institute for Advanced Study, December 16, 1947. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Board of Trustees records

[3] Letter from J. Robert Oppenheimer to Donald Marquis, August 17, 1948. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. School records: Psychology Program at the Institute for Advanced Study, 1948–1966

[4] Jerome S. Bruner, Notes on a Meeting of Psychologists Held at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ, November 23–27, 1949. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. School records: Psychology Program at the Institute for Advanced Study, 1948–1966

[5] Letter from Jerome S. Bruner to J. Robert Oppenheimer, March 1, 1950. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. School records: Psychology Program at the Institute for Advanced Study, 1948–1966

[6] Letter from J. Robert Oppenheimer to Edwin Boring, May 15, 1952. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. School records: Psychology Program at the Institute for Advanced Study, 1948–1966

[7] Press Release, June 19, 1967. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. School records: Development of School of Social Science, 1966–1969

[8] Letter from Carl Kaysen to R. Duncan Luce, April 24, 1968. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. Member records: Luce, R. Duncan, 1969–1972

[9] Letter from Carl Kaysen to Elliott Shore, December 26, 1995. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. School records: IAS Conference, September 15, 1970

[10] Information Processing Seminar flyers. From the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, NJ). Director’s Office. Member records: Luce, R. Duncan, 1969–1972

[11] George A. Miller, “Language, Learning and Models of the Mind.” From the Carl Kaysen papers: von Neumann Conference, 1972