Rahul Ilango, Member in the School of Mathematics, studies computational complexity theory, which quantifies the amount of resources—like time and hardware—needed to solve computational tasks. Ilango has a particular interest in problems that bridge complexity theory with other fields, such as cryptography and proof complexity. He completed his Ph.D. at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he was advised by Ryan Williams, von Neumann Fellow in the School for 2025–26.

What is your elevator pitch for describing your research?

I used to have a long elevator pitch, and then I realized nobody outside of my field understood what I was saying! So now I say this: I try to make algorithms faster, or show they cannot be made faster. I don't even really do the first half—it's almost a setup for the second half. Mostly, I try to make the argument that actually, you can't solve this problem any faster. This is the fastest way you can do it.

What will be the focus of your work while at IAS?

There are lots of fun people here, and there are lots of fun problems to solve! There's a few specific questions that I am pretty interested in, but as long as I'm working on fun problems with fun people—that's my goal.

In a lot of fields, it's not clear definitively what the truth is. You could make a claim that something is true, but there's no absolute sense in which it's true. But in math, we actually have definitive truth, which I find satisfying. It also puts limitations on us: we can only ask questions for which there are definitive answers. But what's great about it is that in other fields, there's this worry that if you're not talking seriously about your research, your research is not serious. But because math has definitive truth, actually, people can be very silly. And I really like the culture of that. I don't know if that's true across all math, but definitely in theoretical computer science, the community is very welcoming.

Where is the most unusual place you have ever worked on your research?

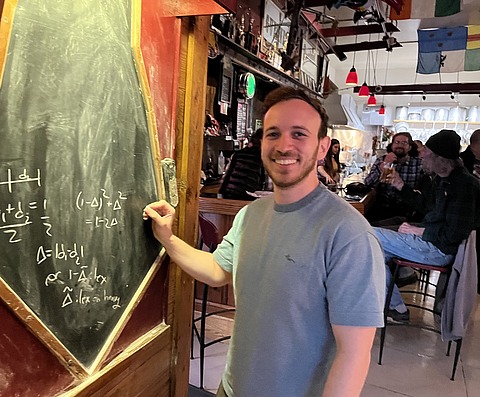

One time, me and, Or Zamir [Member (2021–22) and Visitor (2022–23) in the School of Mathematics], were playing darts at a bar. Or and I had an idea, and we didn't have a chalkboard—but we saw this dart scoreboard, which had a little bit of chalk on it. So then we started doing math on it. We thought it was kind of funny, trying to squeeze it into the tiny space on the board. And being in a bar, doing math! Such nerds.

But I took a picture of it, and I was looking at this picture the other day, and at the math we were doing, and I realized it was wrong. We're making a simple, high school algebra mistake. So we thought we were doing some advanced stuff on the dartboard, and it was really not.

Do you have any superstitions about your research?

There's this technique people use, which is a kind of self-delusion. Whenever you try to prove something, you should convince yourself with all of your heart: "this is true, and it should be easy to prove." You should be fully in that mindset. This isn't my trick—I heard it from Adi Shamir, and I think it even goes back to Manuel Blum. Sometimes you'll be sitting in front of a puzzle, and it'll seem hard. But if somebody were to come and whisper over your shoulder, "Hey, I can tell you something that would make this puzzle easy." Somehow, the idea that that possibility is true, psychologically, helps you to do the thing.

You might be trying to prove something is true or prove something is false. In the morning you'll be like, this is obviously true. It has to be. And then in the afternoon you'll be like, this is obviously false. It has to be. Either way: you have to believe it fully.

Have any IAS scholars, past or present, influenced or impacted your research?

A lot of my research now—one of my most recent papers—builds off of a really cool concept that Kurt Gödel [Frequent Member and Professor (1953–78) in the School of Mathematics] worked on. He was one of the big figures that were at the Institute beginning in the 1930s. He proved this amazing thing, that there are true statements in math that we’ll never be able to prove. Which was kind of a killing blow to some viewpoints of math, which held that we can prove everything that is true. And it turns out that’s not the case! There exist, vexingly, statements that are true that you can’t prove.

This seems like bad news, right? But actually in my research, it's starting to become good news.

You can use it to develop new, powerful cryptographic systems. In cryptography generally, you want to be able to do something easily that your enemy will not be able to do easily. The fact that something is true, but you can't prove it, can give you power that your enemy does not have.

The way that I've been using Gödel combines his work with some of the work that Avi Wigderson [Herbert H. Maass Professor in the School of Mathematics] has done on zero knowledge proofs. Amazingly, he shows that anything you can prove, you can actually prove without revealing anything.

How do you feel now being here, having done work that's inspired by Institute thinkers?

This place has a pretty amazing history, so to be experiencing that and walk around and know these people have been here—it is kind of crazy.

Somebody told me this expression and said it was a climbing idiom: you don't choose your outcome, you choose your battle. What is my responsibility here? It's just to think about problems, and whether I solve them or not, I have no control over that!

Can you talk about what collaboration has meant for your work?

One summer I did an internship at Google, on stuff that wasn't really what I did day-to-day in my Ph.D. Because it was a different area, I had to learn a lot. It was a five-person team. I got to interact with people who knew so much about stuff that I didn't know about, and I knew stuff they didn't know about.

The collaboration itself was interesting to learn from because we worked on it for over a year. And for most of that time, we had absolutely nothing. And so it was kind of an exercise in, "how long are you willing to think about a problem?" And if you enjoy thinking about the problem, then it’s fun.

When I started my Ph.D., I wasn't so much interested in cryptography. And then by working with this team of people who were actually interested in privacy, it seemed like we needed some cryptographic tools to attack this problem. And I ended up learning these tools, and all of a sudden my toolkit grew to both of these things. Then there emerged all sorts of interesting questions at the intersection of complexity and cryptography that ended up changing the course of my Ph.D.