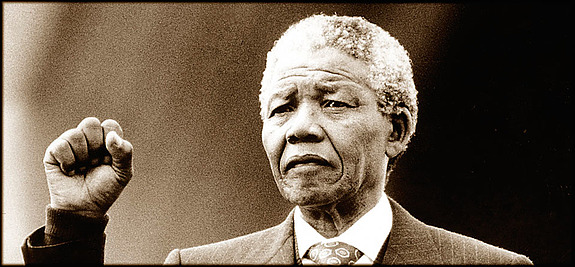

The Legacy of Mandela’s Life: A Political and Moral Hero

On the eve of South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, few observers thought that the day would pass without bloodshed. A smooth transition toward democracy seemed very unlikely. Having been in a state of emergency from 1985 to 1990, the country had suffered from years of civil war–like conditions. In the early 1990s, the police force of the apartheid regime, white supremacists, and secessionist Zulus had massacred members of the African National Congress. The charismatic General Secretary of the Communist Party, Chris Hani, had been the recent victim of an assassination ordered by a member of the Conservative Party. And during ANC meetings the crowd would sing the combative chant “Kill the Boer.” Thus, it was an unlikely transition, even more so because South African President Frederik de Klerk was accused of supporting the Inkatha Freedom Party of Mangosuthu Buthelezi, which was implicated in the violent outbreaks.

The elections were marked by the enthusiasm surrounding the universal right to vote for the first time and there were no major incidents that would have marred the momentous event. The ANC won with 62 percent of the votes, and Nelson Mandela, freed four years before after twenty-seven years of imprisonment, became the first president of a democratic South Africa while his former enemies, Frederik de Klerk and Mangosuthu Buthelezi, were appointed Vice President and Minister of the Interior, respectively. This unlikely display of national unity was the result of tough negotiations conducted by the president of the ANC with the whites who had been in power, sought to preserve their privileges, and feared revenge from the black majority, as well as with his own party, which was hardly inclined to compromise with those who had enforced the racist policy of segregation and oppression for decades.

A determined militant fighting against apartheid (he refused to be freed under conditions) as well as a pragmatic planner of democratization (he accepted that white civil servants would keep their current positions), Nelson Mandela thought that “courageous people do not fear forgiving, for the sake of peace.” When the South African Springboks won the Rugby World Cup in 1995, he wore the team’s jersey, an execrated symbol of white racism, when he handed the trophy to the captain—a very powerful gesture of national reconciliation.

It is this two-sided image of political and moral hero that South Africans will remember of this man who transformed their country from an object of international ostracism into a model nation. Due to this image, he also became a consensual figure for the entire world because his actions reinstated the rights of those who had been oppressed and restored their dignity without perpetuating resentment or inciting retaliation. The establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 1996 to 1998, which allowed the government to grant amnesty to those who were guilty of major violations of human rights provided that they confessed their actions, has become an obligatory point of reference for countries transitioning from periods of dictatorship or conflict, even if many in South Africa have regretted an overly lenient justice toward the perpetrators and only modest reparations for the victims.

Unlike his successor, Thabo Mbeki, a vindictive politician, Nelson Mandela was not what Nietzsche calls a “man of ressentiment.” Tirelessly engaged in the present and resolutely facing the future, he never dwelled on the past, but did not try either to erase its trace like many wished to do after apartheid in order to absolve those who had instituted or simply tolerated the regime of their responsibility. For him, forgiving did not mean forgetting. And he was critical of white people who, after having exploited the natural and human resources of the country, left it under a pretext of fear that they had actually contributed to fuel in spite of the benevolence shown by the government toward them.

Indeed, as head of state, Nelson Mandela tried to reassure the white minority in order to undermine the position of extremists who would most likely resort to violence as well as to prevent companies and capital from fleeing the country. Despite the Restitution of Land Rights Act for the reparation of damages due to the 1913 Natives Land Act, which had allowed the dispossession of the majority of black people, land reform remained very modest. And although an ambitious economic plan of equal opportunity was put in place, fewer than ten percent of all companies quoted on the stock exchange were owned or managed by blacks at the end of his first and only presidential term. Insofar as the nationalization of large companies and the plan for the creation of jobs under the Reconstruction and Development Program were concerned, they were abandoned in exchange for a liberal policy in line with the requirements of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Within the ANC, critics certainly pointed out this apparent renunciation of the principles of social justice promoted by the party. However, the considerable achievements that were accomplished in a difficult environment should not be underestimated. During the five years that Nelson Mandela was in power, all administrations, which had been segregated according to four racial groups under apartheid on a local as well as national level, were unified, allowing the same services for everyone; various grants for the retired, the disabled, and poor or orphaned children were allocated equitably to all social categories; free health care became available to pregnant women and children under six years; poor rural and suburban areas benefited from a network of roads and infrastructure; and numerous low-income houses were built. Thus, even if he was unable to reduce the socioeconomic inequalities and delayed taking measures against the AIDS epidemic, the former South African president still accomplished an impressive task by building this “rainbow nation” as archbishop Desmond Tutu called it.

The political and moral lesson to be drawn from Nelson Mandela is thus his determination to fight against oppression and injustice, his refusal to renounce his principles and values, and his unfailing courage to make difficult decisions and to speak the truth—a valuable lesson for the contemporary world.

This text is a slightly modified version of an obituary for Nelson Mandela published in Le Monde on December 7, 2013.