Britain’s Moment in Palestine

The British Mandate in Palestine may be divided roughly into four distinct periods.

1. 1915–1920: In February 1915, a small Turkish force, led by German officers, managed to cross the Sinai desert and reach the Suez Canal, the imperial artery to the “jewel in the (British) Crown”—India. This shattered Britain’s previous strategic conception that no modern army could attack the canal from the North, and led her to move her defense line north, to Palestine. In November 1917, the British issued the Balfour Declaration, which offered to help the Zionists establish a Jewish national home in Palestine—provided that nothing was done to “prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

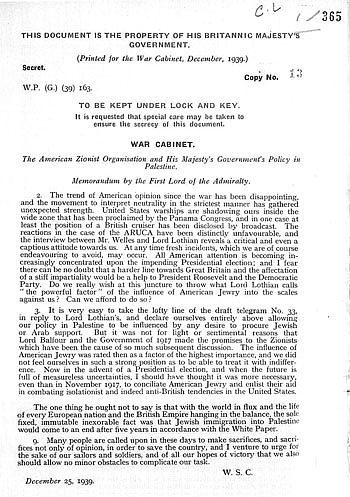

At one of the most critical junctures of the war, the Declaration served many purposes, not the least of which was as a propaganda tool: it harnessed for Britain the alleged, all-powerful influence of international Jewry (the cabinet feared that the Germans were about to preempt them with a Declaration of their own). It also served British military and strategic interests. Britain’s Zionist proxies enabled the government to demand Palestine solely for itself (thereby finessing the French out of Palestine, as had been agreed in the Sykes-Picot share-out of May 1916). President Wilson was persuaded by prominent American Zionists to agree to the Declaration, in effect, to a British occupation of Palestine, even if still under Turkish rule.

These interests prevailed over the objections of the Anglo-Jewish establishment, and of a senior cabinet Jewish Minister, who opposed Zionism. There is no little irony in the fact that the culture and public discourse of the country that issued the Declaration was permeated with anti-Semitism—not only the working classes, who resented the intrusion of Jewish immigrants from Czarist Russia, but also the press and the British Parliament.

2. 1920–1936: After the war, the government’s support for the Zionists encountered fierce criticism, both by Palestinian Arabs, and at home, by the Conservative right-wing and its press, dominated by the press barons, Lords Northcliffe (whose empire included The Times) and Beaverbrook. They complained that the Declaration had been a wartime exigency, but should not be allowed now to embroil Britain with the entire Arab and Muslim worlds. During a debate on Palestine in July 1922, William Ormsby-Gore, Conservative M.P., and a future Colonial Secretary (1936–38), referred to the “anti-Semitic party” in the House:

. . . those who are convinced that the Jews are at the bottom of all the trouble all over the world. Whether they are attacking an anti-Zionist. . . or Zionists, or rich Jews, or poor Jews . . .”

In October 1922, the Lloyd George coalition government was replaced by a Conservative administration. In view of the latter’s condemnation of the Balfour Declaration, there was a general expectation that the Conservatives would abrogate it. In June 1923, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin set up a cabinet committee to study the problem. The committee, headed by the Colonial Secretary, but dominated by Lord Curzon, concluded that Britain must continue to support Zionism if it wished to retain Palestine. The committee’s report, endorsed by the full cabinet, recommended: 1. Britain must remain in Palestine, if only to prevent any rival power from getting too close to the Suez Canal; 2. Britain could not afford to lose international face by reneging on the Balfour promise, now enshrined in the League of Nations mandate; 3. Britain had become dependent upon the import of Jewish capital for administering the country, at a minimal cost to the British taxpayer.

At no time was this financial dependence on Zionists more pronounced than in 1930, when the minority Labor government issued a new White Paper on Palestine. This would effectively have halted all further development of the Jewish national home—no more land sales to Jews, and no further Jewish immigration. The new policy represented the consensus of the Colonial Office establishment, both in London and in Jerusalem, following the so-called “Wailing Wall Disturbances” of August 1929.

But one year after the Wall Street crash, with the British economy sinking into deep recession, no British government dared to offend “international Jewry” who, it was feared, were able to turn the White House against Britain. Further, the Conservative Opposition, and the Liberal rump led by Lloyd George (upon whose votes Labor depended) took the opportunity to vilify the government. In the parliamentary debate on the White Paper, the Opposition humiliated the government, accusing it of anti-Semitism and of betraying an international pledge. The White Paper was not even put to the vote and never became law.

Following secret negotiations between a Zionist delegation and a cabinet committee, in February 1931, the Prime Minister read into the protocols of the House of Commons a letter from himself to Dr. Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader. His letter “re-interpreted” (in effect rebutted) the 1930 White Paper and remained the law of the land in Palestine until 1937. This hiatus provided a window of opportunity for the Zionists. From 1931–1935, while Nazism and anti-Semitism reared their heads in Germany and in Eastern Europe, nearly 200,000 new Jewish immigrants arrived in Palestine, doubling the size of the Jewish community.

3. 1936–1939: But in the mid-1930s, all other policy considerations were swept aside, when the resurgence of Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany threatened a new world conflict. Britain’s need of the strategic assets of the Arab states (oil and strategic bases) became paramount. Between 1935–36, Britain’s international standing suffered a series of critical reverses; her failure to stop the Italian conquest of Abyssinia, and, in March 1936, taking advantage of Britain’s pre-occupation with the Italian threat to Egypt, Nazi Germany re-occupied the Rhineland, in clear violation of the Treaty of Versailles. Both developments were regarded by the Arab world as indications of British weakness, in the face of the dynamic Central Powers.

In 1936, the Arabs reacted with a series of demands for greater independence. In January, Syria’s Arabs declared a general strike, demanding the end of the French mandate; in August, the Egyptians secured a new treaty that included a reduction of the British garrison and its removal to the Canal Zone base, and the promise of full independence by 1956. In Palestine, the Arabs declared a general strike in April 1936, which turned into a full-scale rebellion, which lasted intermittently until early 1939. At the rebellion’s peak, in the summer of 1938, the British all but lost control of Jerusalem and extensive areas of southern Palestine. The crisis in Palestine coincided with the Munich crisis.

In May 1939, on the eve of World War II, the British enacted a new White Paper on Palestine, designed to appease the Arab states. It asserted that Britain had fulfilled its pledge to facilitate the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine, and promised to set up an independent Palestine state within ten years. A further 75,000 Jewish immigrants would be allowed into Palestine over the next five years, after which all further immigration would be conditional upon Arab assent. This figure was calculated to ensure that the Jewish population of Palestine did not rise above its current one-third minority.

4. 1939–1948: During World War II, two major developments transformed the Arab–Zionist conflict in Palestine into an intractable imbroglio. The first was the Holocaust, the extermination of six million of Europe’s Jews by Hitler’s “Final Solution.” This created an irresistible demand for permitting the entry of the survivors into Palestine, over and above the White Paper’s 75,000. The second development was the adoption by the Arab League in late 1944 of the Palestinian Arabs’ cause. This meant that any British move in Palestine that displeased the Arabs would risk the denial to the West of Arabian oil and strategic bases.

After the war, the British Foreign Office and the U.S. State Department both favored a Palestine settlement that would be approved by the Arab world, i.e., no Jewish state. President Truman agreed—especially when the Cold War held the potential for turning at any moment into World War III. But Truman was forced by his political advisers to lean toward a pro-Zionist solution, i.e., a Jewish state in a part of Palestine (partition). Truman’s subservience to the Zionist lobby (the Jewish vote and Jewish contributions to the Democratic Party) persuaded the British to throw in their hand. In February 1947, they referred the Palestine Mandate back to the United Nations, with no recommendations. On November 29,1947, the U.N. voted to partition Palestine into Arab and Jewish states. The first Arab-Israeli war had become inevitable.