Paul Dirac: The Mozart of Science

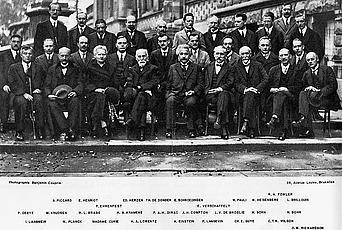

When Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, Albert Einstein had already left the country. He was in the United States and in contact with the founders of his new academic home, the Institute for Advanced Study, which would open in fall 1933. He and the mathematician Oswald Veblen would be the first Faculty members and plans were afoot to recruit their colleagues. When Veblen asked Einstein in March to name the physicist he would most like to join him, Einstein chose the English theoretical physicist Paul Dirac as “the best possible choice for another chair.”

Einstein’s recommendation was not controversial. Dirac, then thirty, held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics—once occupied by Newton—and was about to become the youngest theoretician to win the Nobel Prize for Physics, a record that stood until T.D. Lee, then a Member of the Institute, won the Prize in 1957. As Einstein and the Institute’s founders knew, it was going to be difficult to prise Dirac from his comfortable life at the University of Cambridge, where he had been based for almost a decade. In the end, it proved impossible to persuade Dirac to take a post at the Institute, but the Institute succeeded in becoming his second academic home for the next thirty-five years.

In 1931, a year after the Institute was founded, Dirac had been invited to Princeton University by Veblen, then a professor at the University. By that time, Dirac had established himself as a world-class scientist, one of the discoverers of quantum theory, a revolutionary set of laws that describe matter on the smallest scale. Many of the early papers in this field now look dated and tentative, but Dirac’s have a timeless purity, written with a special grace, mathematical elegance, and concision. He never used a paragraph where a sentence sufficed, nor did he ever deploy an unfamiliar word when a common one would do.

In the view of School of Natural Sciences Professor Emeritus Freeman Dyson, “Dirac’s great discoveries were like exquisitely carved marble statues falling out the sky, one after another.” One example of this was the beautiful equation Dirac found to describe behavior of every electron in a way consistent with both quantum theory and the special theory of relativity. In 1928, when he published this equation, physicists all over the world regarded it as wondrous, not least because it accounted naturally for the electron’s spin, a mystery since experimenters discovered it three years before.

When Veblen’s invitation arrived in Cambridge, Dirac was working in St. John’s College on a new approach to theoretical physics. Dirac encouraged theoreticians to proceed not by taking their cues from new experimental results but by using appealing mathematics as their primary inspiration. Dirac described this idea in a landmark paper whose main purpose was to set out an innovative theory suggesting the existence of a single magnetic pole, hitherto undetected. Almost in passing, he also tentatively suggested the existence of an anti-electron, a particle with the same mass as the electron but with the opposite electrical charge. This paper, which appeared in American libraries a few days before his arrival in Princeton at the end of September 1931, formed the basis of his work in the plush new Fine Hall (now Jones Hall) at Princeton University.

On the day after he arrived, Dirac gave a joint seminar with the Austrian theoretician Wolfgang Pauli, each of them describing how theoretical reasoning had led them to suggest the existence of a new particle. The colloquium—“a first national attraction,” Pauli wrote—was an exciting beginning to the new academic term for Princeton’s physicists. Dirac began by reviewing his theory of isolated magnetic poles, then Pauli went on to argue that there might exist an electrically neutral particle of roughly zero mass (later dubbed the neutrino). At that time, both contributions were regarded as extremely daring because, as Dirac later explained, it was almost universally assumed that the number of fundamental particles is tiny and that the existence of new ones (if there were any) was a matter for experimenters to explore, not theoreticians.

A few weeks later, during a lecture course at the university on quantum theory, he spent just a few minutes discussing the anti-electron. Although he had hinted at the possibility of such a particle in his landmark paper, it was in Princeton that he came closest to predicting its existence. Contrary to current myth, hardly any physicists took Dirac’s idea seriously, and there was no fanfare when the experimenter Carl Anderson first caught sight of the anti-electron (the first observed anti-matter) among the cosmic rays raining down from the summer skies over Los Angeles in 1932. Anderson was unaware of the prediction made by Dirac, who, in turn, knew nothing of the discovery until a few months later. Today, this event is usually regarded as one of the great triumphs of modern science, because Dirac’s prediction is widely taken to be the first motivated solely by faith in pure theory, without a hint from data.

Dirac began his first yearlong sabbatical at the Institute in the fall of 1934, a stay that later stood out as one of the most memorable times of his life. Working alone as usual, he intended to use his new approach of growing fundamental physical theories from purely mathematical seeds. But the year was dominated by two diversions. First, his closest friend, the Russian experimenter Peter Kapitza, was detained against his will by Stalin’s police during a summer visit when on vacation from Cambridge. As soon as Dirac heard about this, he spent months trying to get his friend released, on one occasion lobbying the Soviet Ambassador in Washington. Dirac’s second distraction began over lunch on Nassau Street when the Hungarian theoretician Eugene Wigner introduced him to his sister, who would later become Dirac’s wife, Manci Balazs. The Diracs were in many ways opposites—he was shy, modest, taciturn, and he often appeared cold and distant; she was outgoing, confident, talkative, a warm and considerate friend. It was an unlikely relationship, but their marriage worked and was ended only by his death almost half a century later.

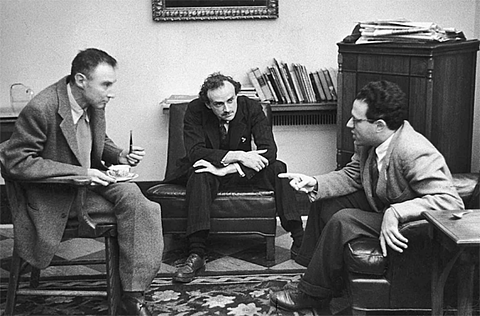

During the war, Dirac contributed more to engineering than he did to physics. Mainly working at home in Cambridge, he did demanding calculations for the British team working on nuclear weapons and developed a method of isotope separation using an apparatus with no moving parts, an invention he had made a few years before (the nuclear power industry still uses some of the concepts he introduced). After the conflict, he escaped the postwar austerities in the United Kingdom by accepting an offer from his old friend, J. Robert Oppenheimer, newly appointed Director of the Institute, to spend a sabbatical there in the 1947–48 academic year.

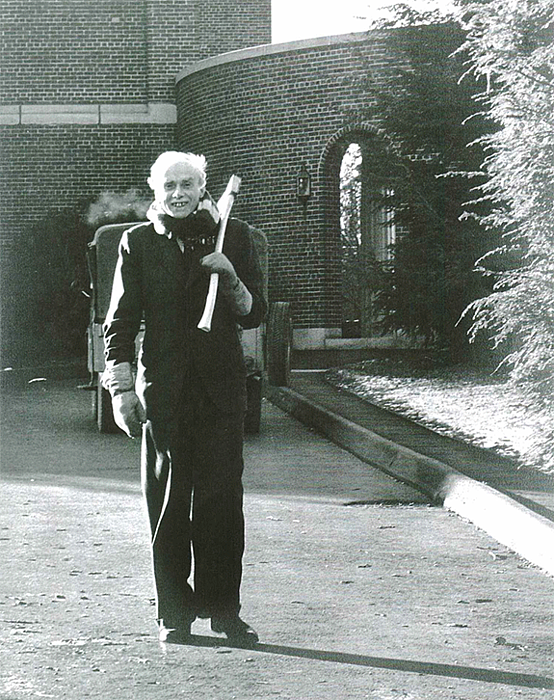

In this restorative stay, Dirac did much-admired work on magnetic monopoles and quantum theory, regaining research momentum that he had lost during the war. The calm, the excellent facilities, and the quality of the academic company at the Institute were just what he needed: he worked in Fuld Hall alongside several friends—Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, and Oswald Veblen—and toward the end of his stay, he made the acquaintance of a scientist he later much admired, Freeman Dyson. Dirac worked hard on weekdays but reserved weekends for family and for socializing with his colleagues (his elder daughter long remembered having tea one Sunday with the Einstein household). On Saturday mornings, Dirac would set off with an axe over his shoulder to help Veblen and others clear another path in the Institute’s woodlands.

Having been assured by Oppenheimer of a permanent welcome at the Institute, Dirac stayed there many times during the next eighteen years. On one occasion, a failure in the arrangements made the front page of The New York Times: in the spring of 1954, at the height of the McCarthy era, Oppenheimer heard during a weekend break in his security hearing that Dirac had been refused a visa to travel to the United States (probably because of Dirac’s friendship with several Soviet scientists and his sympathies for Stalin’s government in the 1930s). After an outcry among American physicists, the government granted Dirac his visa in early August, but it was too late. He had already made arrangements to spend his year in India, having tried in vain—perhaps to cock a snook at the authorities—to take his sabbatical in Russia.

Dirac continued to be productive in his fifties and sixties. During his sabbatical at the Institute in 1958–59, he developed an important new way of formulating Einstein’s theory of gravity, using his own preferred way of formulating the laws of quantum theory based on techniques originally set out by the Irish mathematician William Hamilton. Four years later, Dirac returned to quantum theory, beginning work that would later be valuable in research on gauge theories and string theories. He wrote these papers in his characteristic style, developing each new idea with an elegance and simplicity that gave the impression that the theory could not be realized in any other way, in much the same way as a great composer’s music often has a sense of inevitability. The Hungarian physicist Nandor Balazs had this analogy in mind when he described Dirac as “the Mozart of science.”

From the early 1930s, he was convinced that quantum theory was unable to give a mathematically coherent account of even the simplest interactions between electrons and photons (particles of light) because, in his reading of the equations, they generated meaningless infinities when used to predict measurable quantities that must, perforce, be finite. For him, a fundamental theory of nature must be mathematically beautiful, whereas advanced quantum theory was unendurably ugly. Decades later, Dirac refused to accept the consensus that these problems had been solved, and he insisted repeatedly that nothing short of a radically new approach to quantum theory was needed.

Aware that many theoreticians at that time privately regarded his views as principled but impractical or even cranky, Dirac’s morale was sometimes low. No doubt with this in mind, the late Princeton physicist John Wheeler wrote him a characteristically sensitive, encouraging note on his eightieth birthday, August 8, 1982: “I write to tell you what I am not sure you divine, how many of the younger generation as well as older ones look up to you as a hero, as a model of how to do things right, of passion for rectitude as well as beauty.” At about the time he received this note, Dirac talked at a summer school in Sicily with one of his young admirers, Edward Witten, later a member of the Institute’s Faculty. The admiration was mutual: in 1983, in a handwritten note to the chair of the Papal Awards committee, Dirac recommended Witten for his “brilliant solutions to a number of problems in mathematical physics.” This seems to have been the last reference Dirac wrote.

Dirac’s final visit to the Institute had been in 1979, when he attended the symposium to mark the centenary of Einstein’s birth. By then, Dirac had accepted a Visiting Professorship at Florida State University in Tallahassee, partly so that he and his wife could be close to their elder daughter, Mary. Dirac was made exceptionally welcome in Tallahassee, where he did unconventional research on cosmology when he was not giving lectures all over the world. He had a comfortable and contented retirement, but I suspect it would have been even happier if he had accepted one of the offers the Institute had made him. In interviews to the Florida press before he died in 1984, he spoke warmly—and with more than a hint of nostalgia—of the Institute. It was, he said, “a paradise.”