Spinoza and The Origins of Modern Thought

In his Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, the Dutch philosopher Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677) explained the fundamental principles of the state he had defined:

“But its ultimate purpose is not to dominate or control people by fear or subject them to the authority of another. On the contrary, its aim is to free everyone from fear, so that they may live in security, so far as possible. That is that they may retain to the highest possible degree their natural right to live and to act without harm to themselves or to others. It is not, I contend, the purpose of the state to turn people from rational beings into beasts or automata, but rather to allow their minds and bodies to develop in their own ways, in security, and enjoy the free use of reason, and not to participate in conflicts based on hatred, anger, or deceit, or in malicious disputes with each other. Therefore, the true purpose of the state is in fact freedom.”

During his November 1 Friends Forum talk “Spinoza. Or the Failed Jewish Businessman Who Changed the World Through Philosophy,” Jonathan Israel, Professor in the School of Historical Studies, credited Spinoza “as the first great philosopher who was a democrat.” Equally important and of particular relevance to Americans, Israel said, Spinoza was “the first philosopher to insist that you can’t build a free, stable, and successful society, or a moral order that is stable, if theological criteria, and it doesn’t matter which theological criteria, are allowed to be the basis of its principles.”

Israel’s talk drew on his extensive research on the impact of radical thought (especially Spinoza, Bayle, Diderot, and the eighteenth-century French materialists) on the Enlightenment and on the emergence of modern ideas of democracy, equality, toleration, freedom of the press, and individual freedom. His recent book Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670-1752 (Oxford University Press, 2006) continues the major revisionist study he began in Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650-1750 (Oxford University Press, 2001), in which he credits Spinoza as the originator of the core principles of modern thought.

In his talk, Israel spoke about the “rival mythologies” or “the different grand narratives explaining Spinoza’s legacy, each of which is quite different from and incompatible with the other.” Prime among them is what Israel calls the “Voltaire Syndrome, because Voltaire was the earliest and perhaps the most important of its propagators. This is the myth according to which virtually nobody ever read Spinoza. Or of the few that did, practically no one understood him, and of those who understood him, practically none was ever influenced by him.” As Voltaire wrote in 1776, Spinoza “was a philosopher of whom everyone spoke but no one actually read, and who even if he undeniably had a huge reputation, had no discernible impact,” Israel said.

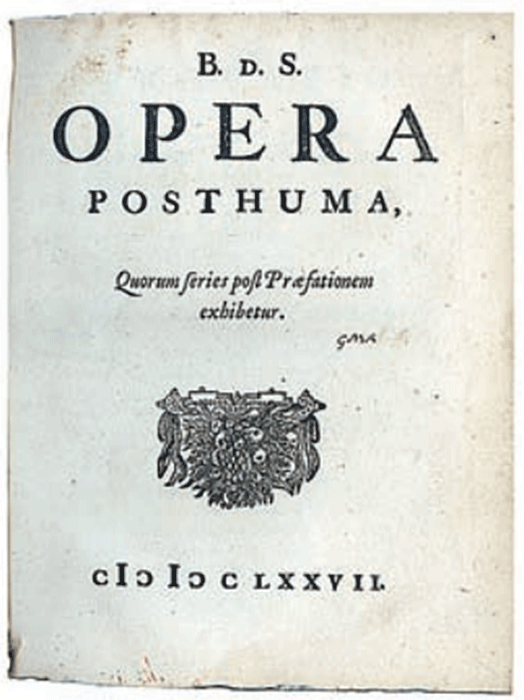

This incorrect and misleading impression of Spinoza’s influence, Israel stated, “has been asserted so many times in modern books that it can be regarded as a long-established cliché, even though this was certainly not the dominant image before 1800.” A more accurate account, said Israel, is that Spinoza’s influence was wide and profound and that Spinoza himself “actively sought to establish an underground philosophical sect, the purpose of which was to spread a particular kind of emancipatory, libertarian, democratic ideology in society.” Because Spinoza’s philosophy denied the “possibility of miracles and revelation, and hence the divine character of scripture and the divinity of Christ, and denying these things was not allowed in Dutch society or any Western society at the time,” Israel noted, his books, including all reworking and restatements, were banned in the Netherlands in 1678 and printers convicted of publishing Spinozistic texts or reworkings of his ideas were liable to heavy fines and ten years in prison. Hence, Spinoza’s writings, such as his Theological-Political treatise (1670) and his main work The Ethics, which was printed only after his death (1677), were published without his name on the title-page and attributed to false publishers and locations.

From the clandestine philosophical literature inspired by Spinoza that became a major intellectual phenomenon in the early eighteenth century, to Shelley, Coleridge, and Wordsworth, who were all deeply affected by Spinoza’s philosophy, Israel said, “We see how Spinoza was linked, perceptibly linked, with secret underground revolutionary ideology, an ideology which took for granted that the world needed changing and the world should be changed, but that the agent of change should be philosophy, and in particular, his kind of democratic, egalitarian, and libertarian philosophy.”