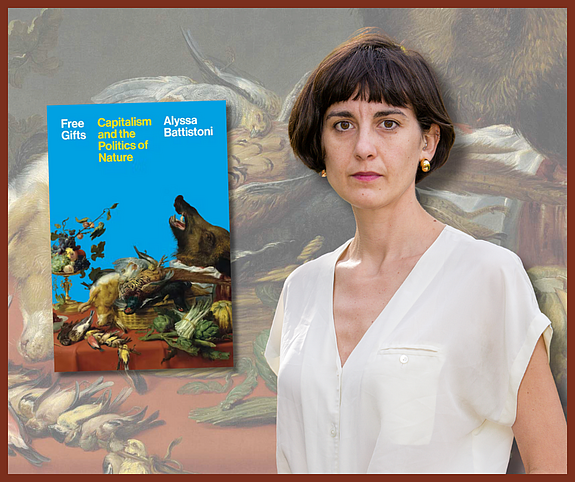

Political and environmental theorist Alyssa Battistoni is interested in what it means to be free, in more than one sense of the word. As a Member (2022–23) in the School of Social Science, Battistoni spent her year at the Institute thinking through value, ecology, and economics as she dismantled a draft manuscript—originally, her Ph.D. dissertation —and reconstructed it into a full-length book.

Published in August 2025, Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nature recycles a term from classical political economy, the titular “free gifts of nature,” in order to interrogate the ways in which the nonhuman world appears within capitalism. Despite nature’s obvious use and usefulness in economic production, some kinds of nature are nevertheless not valued in economic exchange. Think, for instance, of the nonhuman capacities essential to industry, like the wind that powers sails or the land that grows crops. Why haven’t certain ecological processes come to have a price under capitalism, when everything else does?

This question animates Free Gifts; to answer it, Battistoni extends Marxist political economic logics onto the environment and our relationship to it. One central reading, for example, argues that “free gifts” are treated as such because of the wage labor model: nonhumans cannot sell their efforts and therefore cannot earn wages. Across four examples of the free gift—natural agents in industry, pollution in the environment, reproductive labor in the household, and natural capital in the biosphere—the book describes both the enigma of the free gift and how it might help us interpret climate politics today.

In Chapter 4, “No Such Thing as a Free Gift,” Battistoni considers her second kind of “free gift”—the generation of harmful byproducts in commodity production. Here, the economic theory of externality is brought to bear on pollution. Externalities are side effects of economic choices: the term describes the consequences of an action which go beyond an individual actor, and which are not represented in market prices. The externality was one of the most significant economic concepts of the twentieth century, first used in 1920 to describe minor flaws in the market like the unpriced “external effects” of smoky chimneys on laundry. In turn, it has animated the core policy frameworks of late-twentieth-century environmental politics, most obviously via carbon taxes and cap-and-trade programs, and has been taken up in many theories of just climate action.

Yet the externality itself has gone largely unexamined. As Battistoni’s logic goes, it is altogether too simple for capital to abdicate responsibility for the effects of byproduction: expelling surplus matter, by default, is costless. If surplus matter has no buyers, however, it nevertheless has consumers. The ability to impose pollution on others is another aspect of class rule—and the inability to refuse it is a form of unfreedom in its own right.

The relationship between capitalism and nature as articulated in this chapter and across Free Gifts is doubly useful: Battistoni both unfolds a persuasive case for the theoretical underpinnings of our contemporary ecological plight and reads the mechanics of capitalism anew. In so doing, she offers a new, more constructive approach to the twinned problems of market rule and climate change—one in which their entanglement is not taken for granted, but continually questioned, negotiated, contended with. This, in turn, forms the basis of the double-register of “free” in Free Gifts, and its ultimate claim: freedom as a work of the imagination, an ongoing compromise, and a choice about how and what we value.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In your words, what is a free gift?

I think the free gift describes something distinctive to how nature appears in capitalist society. It only makes sense to describe nature as a “free gift” in a world where most things are acquired through the process of commodity exchange; in which most things have a price. It’s in the market that we interact with one another and acquire what we need to survive. The commodity is the elementary social form of capitalism, as Marx famously argues; it has both use value—qualitative features that are useful to human beings—and exchange value, a quantitative form of value—in other words, price. The “free gift,” by contrast, describes things that tend not to have prices: the quality of having use but not exchange value. The free gift appears in a physical form, and has effects in the material world, but it doesn’t appear in the abstract form of value that’s central to capitalism, and doesn’t show up in forms of economic value assessment and accounting. This, I think, can help us understand a lot of features of contemporary environmental politics, from the idea of climate change as an “externality” to the status of “ecosystem services” which work for free.

Can you describe how you arrived at this argument? Where did this book start?

It began as a paper that I wrote in a class in grad school taught by a great professor named Karen Hébert. The paper extended Marxist-feminist critiques of unvalued household work onto nonhuman nature and the unvalued activity of ecosystems. That became the core argument of my dissertation: that we could take Marxist-feminist theories of unwaged work and social reproduction and use them to think about the world of ecological regeneration. I did a historical-genealogical reading of the ways that women’s work and ecosystem activity have been treated in parallel. Those elements are still present in the book, but the argument has changed quite significantly since.

More generally, I started grad school not even thinking I was going to be an academic—just wanting to understand climate change and climate politics. Climate change is an unbelievably massive and overwhelming problem, and I felt like I needed time and space to make sense of it. This book is less about climate politics per se, and more about the broader conditions of how nature is treated under capitalism. That’s sometimes felt like a detour on the way to getting back into climate politics—but I think it’s essential to address some of the larger questions before zeroing back in on climate specifically.

There’s a tension inherent in the book, between theory and praxis. How did this research grow out of your time in community organizing?

I do think that pretty much all of my intellectual work is in some way informed by the experience of organizing for my grad student union. It was where I really learned about politics, in doing and trying to do politics.

In the union, I was always trying to think through the problem of how you get people to act collectively in the face of very difficult challenges. Free Gifts does address labor as one of the central sites of struggle for critics of capitalism: it proposes new ways to analyze labor in relation to nature, and thinks about what it would mean to organize labor in different ways. But it also extends the analysis of capitalist collective action problems beyond labor to other forms of social and political life, like pollution and biospheric preservation. People sometimes say climate change is unprecedented and totally different than any previous political problem. There are ways in which that’s true—but in other ways I think it’s very continuous with some familiar kinds of political problems and practices, and that we can draw on the resources of.

What did your time at IAS mean to you?

I loved my time at IAS. I can’t imagine having finished the book without it. I was part of the Climate Crisis Politics theme year, which was really fantastic: it was a group of brilliant people who read my work closely and gave feedback as I worked to finish the manuscript, but who also just talked through ideas more generally, and helped me take a step back from the weeds of the project. We had a climate film series and a climate fiction reading group. It was invigorating to be able to move between the intensity of holing up and working on a manuscript all day, every day, for weeks, and then emerging and having great conversations with people who were either thinking about the same questions in different ways, or thinking about really different aspects of the problem. My conversations really pushed my thinking and made Free Gifts a richer book. It was totally instrumental to finishing the manuscript. I stayed on campus literally until the last day.