Investigating Imperial Architectures of Data: Q&A with Zeynep Çelik Alexander

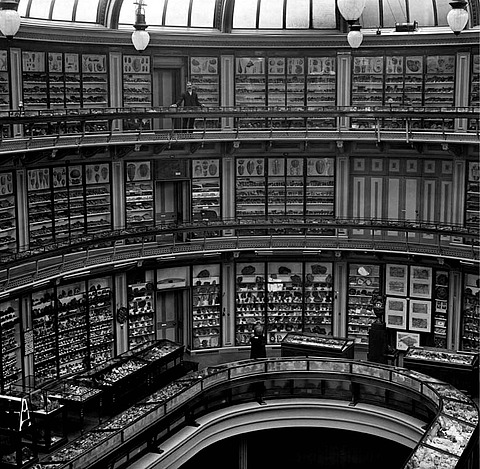

Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Hans Kohn Member in the School of Historical Studies, studies the history and theory of architecture since the Enlightenment. Her current work examines institutions in Victorian London (e.g., the Museum of Economic Geology, the Kew Herbarium, and the Imperial Institute) in which information collected from around the British empire was aggregated and organized to serve imperialist ends in the second half of the nineteenth century. Trained as an architect at Istanbul Technical University and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Çelik Alexander received her Ph.D. from the History, Theory, and Criticism of Architecture and Art at MIT. She joins the Institute from Columbia University, where she is an Associate Professor of Art History and Archaeology.

What will be the focus of your IAS Membership?

At IAS, I’ll be working on the final draft of my book "Imperial Data," which is about clearinghouses of information (public or private entities or agencies for the collection, classification, and distribution of data) in Victorian London. The book is an alternative history of the epistemic order of databases. We tend to associate data and databases with computational technologies, but I argue that they have to do with a particular stage of capitalism.

What is one challenge in your field that people often underestimate?

I’m an historian of architecture, but I don’t always study buildings (although I probably do so more than most of my fellow architectural historians working today). Architectural history is a field that splintered off from art history in the mid-twentieth century and, in the last decade or two, has developed its unique set of questions and techniques. It’s a surprisingly interdisciplinary field. You’ll find that architectural historians engage in intellectual history, environmental history, media theory, data analysis, and even ethnographic fieldwork. They’ll use the built environment to write the most unexpected histories: of obsolescence, for example, or of toxicity. This might be the least understood aspect of our field, but I’m very proud of my fellow architectural historians’ intellectual adventurousness.

Have any IAS scholars, past or present, influenced or impacted your research?

Is there any historian of art or architecture—or, for that matter, any humanist—not impacted by Erwin Panofsky [Professor (1935–68) in the School of Historical Studies]? Jonathan Crary [Member (1993) in the School], has also had enormous influence on my personal intellectual development.

IAS has a long history of collaboration across the four Schools housed on campus. Tell us about a collaboration that has positively impacted your work.

I’ve just completed my seventh year at Columbia, and my intellectual home there has remained an interdisciplinary group called the Center for Comparative Media (CCM). The Center brings together scholars from across the humanities in an attempt to understand the history of media (broadly understood) in a comparative framework that decenters Eurocentric perspectives. Most recently I’ve worked under the roof of CCM with two colleagues: Debashree Mukherjee, a film scholar, and Brian Larkin, an anthropologist. Our project was called “Extractive Media,” and it consisted of a series of seminars and lectures that concluded with a conference in December 2024. It was a rewarding experience that taught me a great deal not only about extractivism but also about how to approach media in novel ways. The three of us didn’t always agree, but, along the way, we learned to make our disagreements productive. And we became great friends.

Where is the most unusual place you have ever worked on your research?

In a basement in Toronto. It turns out that the granddaughter of Wilhelm von Debschitz, an early design educator and one of the protagonists of my first book, lived in Toronto. When I contacted her, she kindly invited me to go through her grandfather’s papers in the basement of her house in Cabbagetown. And she’d cook lunch for me. It was a lovely archival experience—even though the papers were in a bit of a disarray.

What was your dream job as a child?

Archaeologist. When I was a child, summer vacations meant going swimming in the Mediterranean in the morning and visiting archaeological sites in the afternoon. Our family car got stuck in many muddy roads while trying to pursue the yellow sign pointing to an ancient site.

What is one concept in your work you wish more people understood?

My previous book was on kinaesthesia, which is the aesthetic sensation of movement. People usually know what the word means, but when the book came out, I was still frequently mistaken for an enthusiast of the concept—especially in architectural circles where romanticizing the poetics of sensory perception remains a strong tendency. My book, however, was a critical history of a mode of knowing associated with movement and not a call for centering kinaesthesia in architectural discourses.

Is there a childhood memory that shapes the way you think about your academic career?

I grew up in Istanbul. I was generally a good student, but the one subject I truly disliked was history. I put the blame on the “national history” we were taught year after year. After the coup of 1980, the textbooks in Turkey changed, and almost every year, we would have to study the Ottoman Empire all over again, starting from 1299. We had to learn about reigns and battles and treaties—it was absolute torture. If someone told me when I was a child, I’d be a historian when I grew up, I think I’d break into tears.

What is something memorable you read or watched this summer?

I reread a book that I adored when I was 14: Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol (though sadly I cannot read it in the original Russian). It’s an unfinished book, which means there are gaps in the narrative. Back when I first read it, I was taken by the hilarious character descriptions, but this time around I was also impressed by the financial scheme that Gogol dreams up: a conman by the name of Tchitchikov who buys up dead serfs from property owners around the Russian Empire to use them as collateral for his debt. It’s a brilliant book on all fronts.