A Mathematician in the Archives

When Ellen Eischen, von Neumann Fellow (2024–25) in the School of Mathematics, discovered a lost mathematical perspective from the middle of the twentieth century, she dove into historical research for more. Her work reveals what a discipline forfeits when it overlooks the complex reality that shapes it.

Eischen wants us to think more about the human side of math—how it’s molded by the people who practice it, the historical periods they lived through, and the areas where they worked and traveled.

“On some level, we know that life and math intersect,” Eischen says. “We talk about places with significant concentrations of mathematicians and encounters that result in incredible work. At the same time, there’s a prevalent idea that because our subject matter is timeless and universal, the development of mathematical knowledge stands apart from subjective human factors. That isn’t realistic.”

More importantly, Eischen notes, this perspective holds back progress. In a suite of new and forthcoming lectures and essays,1 she shows what’s at risk for a discipline that values truth but does not fully account for how that truth is produced. Her latest research looks back in time to shine light on the mathematician Hel Braun, whose contributions were obscured for reasons that were anything but mathematical.

Into the Archives

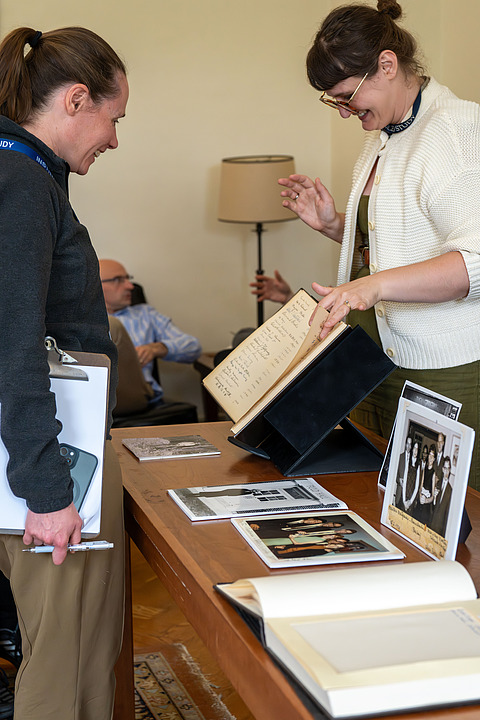

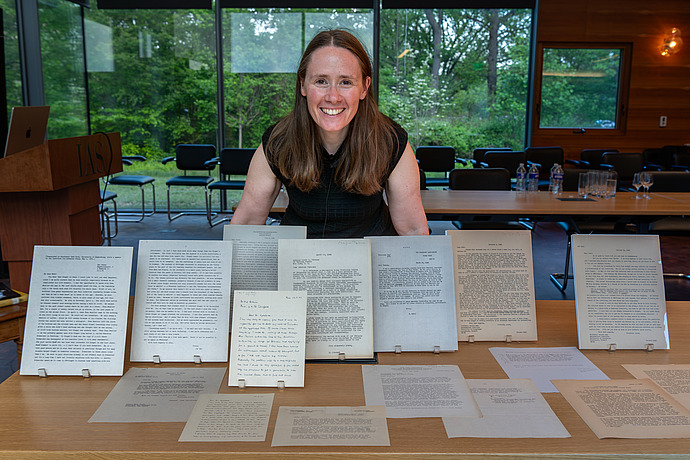

As of today, Eischen’s research has brought her into contact with ten archives across the U.S. and the globe, including the Library of Congress. She’s in active communication with several historians, including historians of mathematics, and she’s preparing to write a book. It’s a surprising pivot for the number theorist—even one as successful as she has been for her creative public engagement work. It all started with a conversation at IAS.

At a daily tea in Fuld Hall, Eischen was chatting with Akshay Venkatesh, Robert & Luisa Fernholz Professor in the School of Mathematics. “Akshay mentioned he was interested in the history of math. I asked him if he had ever heard of a mathematician called Hel Braun.” This is something Eischen had been asking mathematicians for several years. Most have said no. “But Akshay said yes,” Eischen says.

What’s more, Venkatesh had a surprising fact to contribute. There were files on Braun onsite at the Institute’s Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center. She’d been an IAS Member from 1947–48.

“My interest in Braun began with some extraordinary articles I came across,” Eischen says. “They were published in the Annals of Mathematics—our most prestigious journal—in the late 1940s and early 1950s. A mathematician named Hel Braun wrote them, but at that point I’d never heard of her, even though she had produced significant, foundational work in my field.”

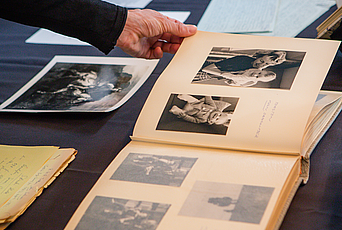

Eischen wasn’t aware that these articles were written at IAS. Newly arrived at the Institute, Eischen felt her curiosity piqued by the coincidence. The opportunity to learn more about the mystery of this lost math—sophisticated and consequential by any measure—was attractive, and Venkatesh soon introduced her to IAS archivist Caitlin Rizzo. Before long, decades-old documents were piling up in front of her.

“That first archival visit at the Institute was a transformational moment for me,” Eischen says. “Even though I’d been more historically oriented than most, tracing results back to their origins and sharing those insights with others, I still had never thought of myself as a history person.” In fact, Eischen shares, she’d been told since childhood that she just didn’t have the “history gene.”

“I really had this idea of myself as someone who just wasn’t good at history,” Eischen laughs. “I remember getting this brutal feedback on a paper on the Great Depression in ninth grade that really affected me. Math came naturally, but it felt like everyone was always telling me I had to work extra hard in history because I just wasn’t cut out for it. And I believed them.”

At the same time, Eischen reflects, she was always drawn to history. Born and raised in the Princeton area, she had a childhood fascination with the region’s role in the Revolutionary War, imagining how troops had moved along familiar routes and homes that had been key in major battles. “I loved visiting the Old Barracks in Trenton and the Thompson-Neely House in New Hope. I would ask the living history actors questions,” Eischen says. “And I remember insisting my dad drive us over the river to Pennsylvania so I could research a school project at the David Library of the American Revolution.” In college too, she had enjoyed a course in the history of science taught by Angela Creager,2 where she refined her skills in finding and interpreting primary sources.

“I actually crossed paths with that ninth-grade teacher later when I was in grad school,” Eischen says, “and he was surprised to hear I was getting my doctorate in math and not in history!” She hadn’t realized his criticism was meant to signal the strong potential of her work. “It shows how unnecessary and limiting it is to polarize different skills and interests,” she says.

As Eischen launched into her archival research at IAS, the opposition between the historical and mathematical began to seem quite brittle. The documents in front of her were telling a story that her mathematician’s eye could discern with remarkable sensitivity.

Telegrams. Letters. Photographs. Paperwork. These humdrum exchanges and bureaucratic records were all anchored by names Eischen knew were driving one of the most monumental eras in math, a time when universities across continents were transforming under wartime pressures and scholars were crossing the Atlantic to saturate new centers of intellectual life.

“I was seeing a network of some of the greatest mathematicians of the twentieth century,” Eischen explains. “These were Hel Braun’s circles, and she was highly regarded in them. But I was also beginning to see this complex overlay of personal, institutional, social, and political issues that would eventually obscure Braun’s story and contributions.”

Decades earlier, Braun had laid the keystone Eischen hadn’t even realized was missing from the foundation of her own research. Today, Eischen wants to account for that loss.

Out of the Shadows

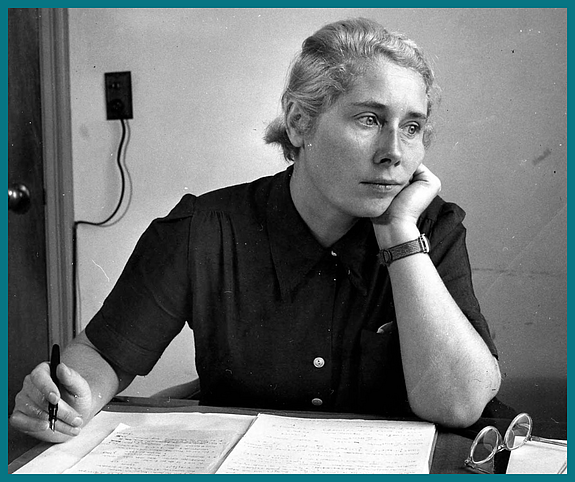

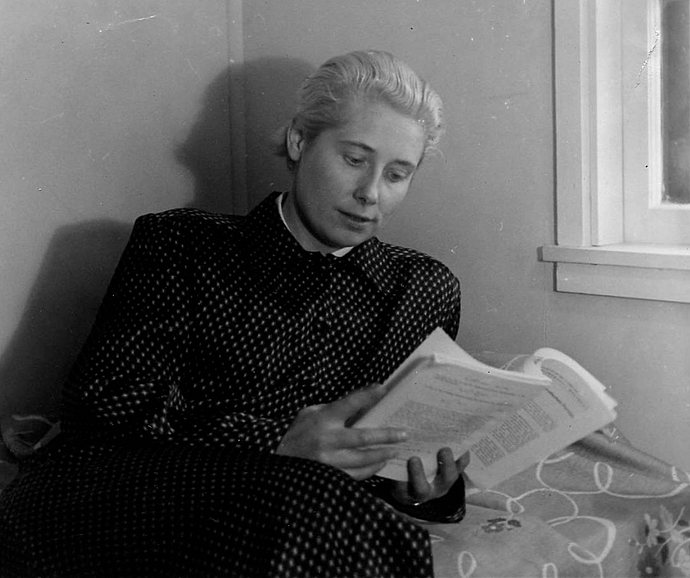

Hel Braun was born Helene in a generation full of Helenes. She took the name Hel as a child to distinguish herself in school, and kept it for the rest of her life.

Her success in math was remarkable by any standard, and exceptionally so for a woman of the time—though she never publicly acknowledged a challenge or discrepancy of experience. She was the second woman ever to habilitate—an advanced stage of qualification that comes after a doctoral degree but before a professorship—at what was, at the time, the world’s leading center for mathematical innovation, the Mathematical Institute in Göttingen. The revered mathematician Emmy Noether,3 who fled Germany in the 1930s, was the first.

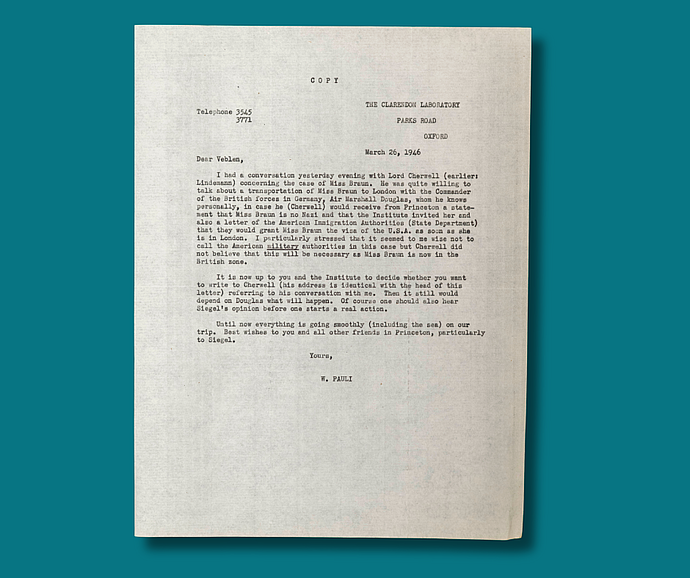

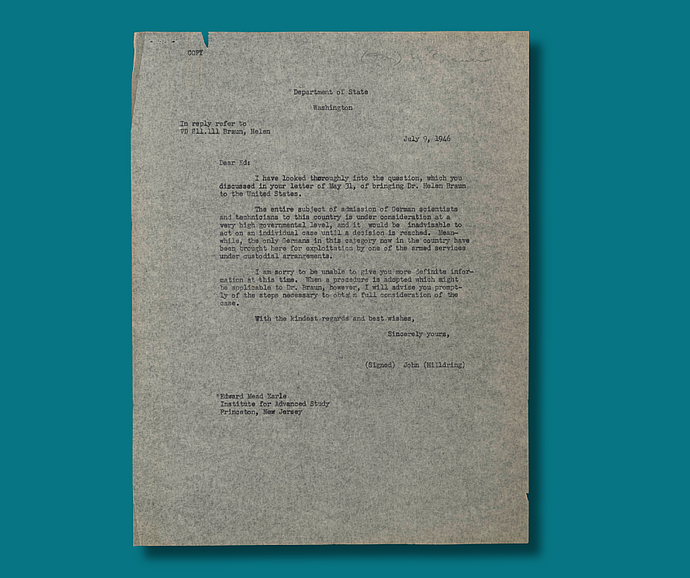

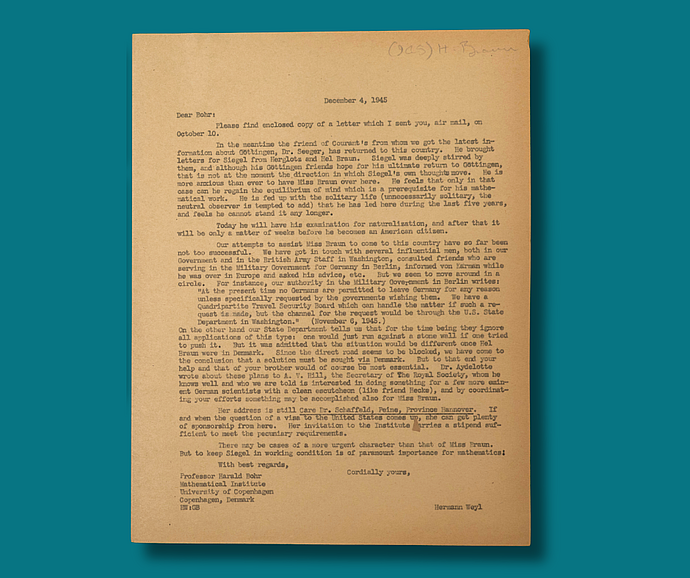

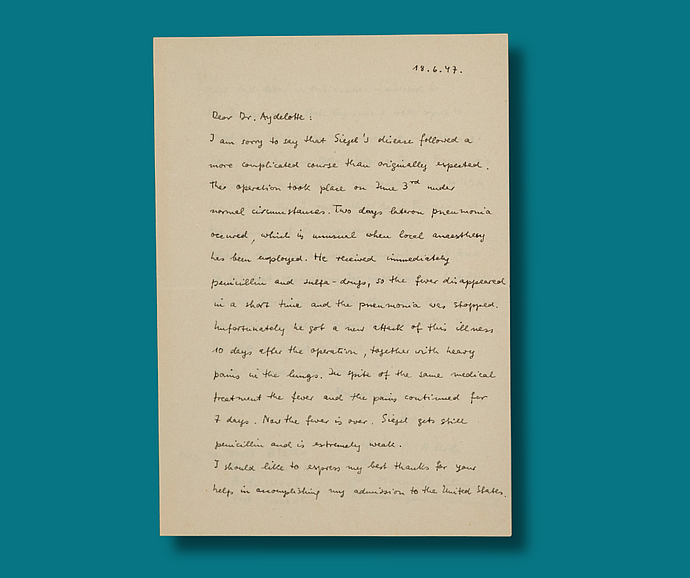

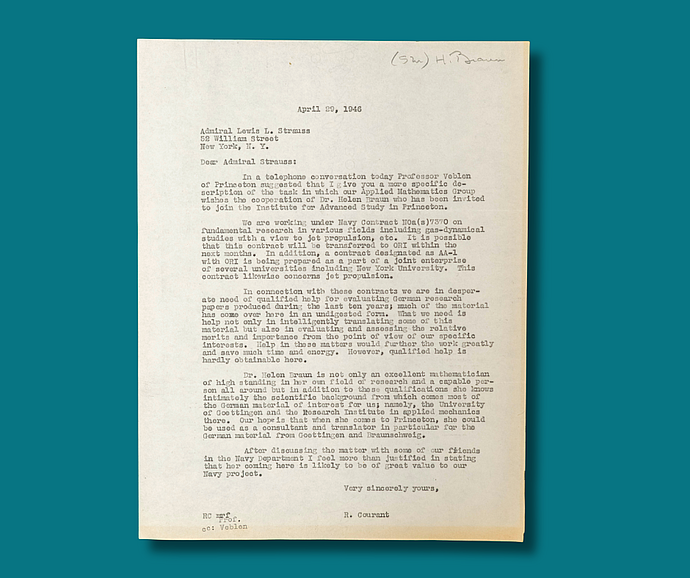

Braun too came to the United States through the persistent advocacy of a leading mathematician, her former Ph.D. advisor and close colleague Carl Ludwig Siegel. However, she couldn’t be welcomed in the States until after the war had ended.

Siegel, a permanent Faculty member (1945–51) in the School of Mathematics4 and arguably the leading

mathematician of his time, had been eager to have her join the vibrant community of scholars in Princeton. But the state of the world and her own hesitations about their relationship put a damper on the plans. “Siegel had strong feelings for Braun, which weren’t reciprocated,” Eischen explains. “He referred to her as his fiancée and there are some accounts that they lived together in Princeton, but there’s no evidence either of those things was true.”

What was true was that Siegel championed Braun’s research as vital, not only to number theory but to all of mathematics. In 1947–48, having fulfilled the U.S. government’s criteria for intellectual visas (anti-Nazi, with knowledge of value for the country, and financially secure), she flourished at the Institute and produced the extraordinary publications that began Eischen’s archival journey.

Yet, by the time Braun left IAS, at the end of a single year of residence, she and Siegel had fallen out. “For most of his life, Siegel refused to reconcile with her,” Eischen says. Braun returned to Germany, where she led a long and successful career in math, publishing work that branched out fruitfully in many directions. But memory of her impact faded as time went on.

This series of papers she produced in the late 1940s and early 1950s—the first two of which she wrote at IAS—introduced sophisticated mathematical objects called Hermitian modular forms, which opened doors to new avenues of research. Under the unofficial conventions of the field, they would normally have been named after Braun and been called Braun modular forms. However, there is no formal process for naming objects after mathematicians. “The reason they never became Braun modular forms is that no one started calling them that,” Eischen says.

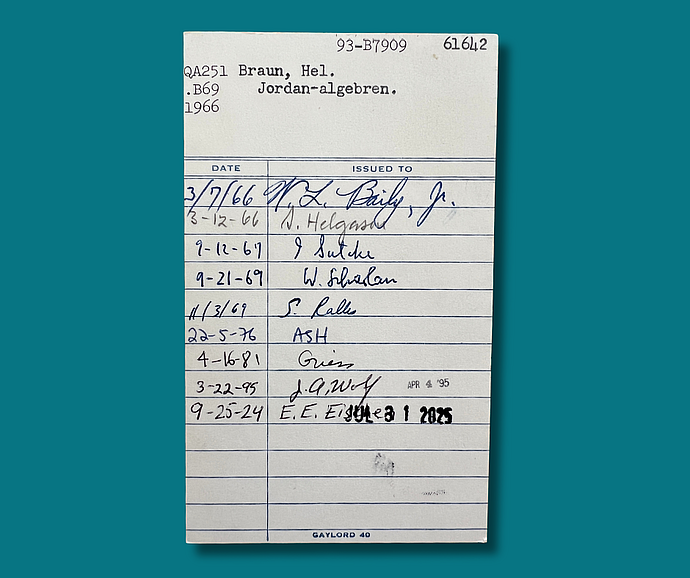

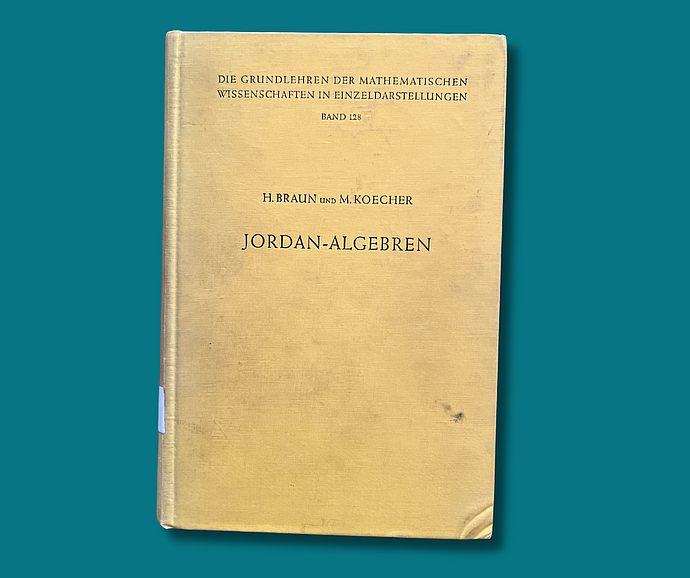

Still, Eischen points out, Braun wasn’t forgotten for this reason alone. Braun’s contributions were enormously influential, but a broader collection of non-mathematical factors limited the discipline’s ability to retain a reliable record of her impact. “She actually applied to come back to IAS in the 1960s to research connections between automorphic functions and Jordan algebras, a topic she had been investigating with a colleague named Max Koecher,” Eischen notes. “The rejection letter she received stated that IAS was looking to sponsor junior scholars that year. So, she and Koecher stayed in Germany, where they ended up writing the first-ever book published on Jordan algebras. It was very successful, ending up in the Institute’s Mathematics/Natural Sciences Library and in the hands of many major mathematicians. I was blown away by the borrowing record on that book, it’s tremendous.”

Despite the influence her work had, Braun’s citation record remains thin. A German-language book had limited longevity in a discipline adopting English as its lingua franca.

Institutional politics also played a role. Braun capped off her career, happily, with a prestigious professorship at the University of Hamburg. In 1968, she succeeded Helmut Hasse to take over one of the highest-level academic positions in the German university system. When she retired, however, in 1981, the position was discontinued due to institutional politics and memory of its significance diminished.

Towards New Perspectives

“The collective forgetting of Hel Braun has been silently undermining years of work,” Eischen explains. “Math is cumulative. We layer our inquiries on top of our predecessors’ and build off each other’s results. When something goes missing, it weakens the entire structure.”

And, as math accumulates new strata of knowledge over time, it also strengthens the mathematician’s ability to make significant internal connections. Mathematicians often make progress by finding connections between ideas or problems that, at first, seem completely unrelated. When they notice that two different ways of thinking about something in math are linked, it can reveal deeper patterns or truths that apply broadly across mathematics. Key among Eischen’s objects of inquiry and active in her current research program are Braun’s Hermitian modular forms—which allow mathematicians to investigate geometric phenomena and arithmetic properties in a single lens—and the broader class of automorphic functions to which they belong.

“During the same period that I was doing this archival research, I was working on a joint project with mathematicians Giovanni Rosso and Shrenik Shah,” Eischen shares. “And we were stuck. We couldn’t find a systematic strategy to addressing a challenge that had arisen in our research. We were working with an approach called the Rankin-Selberg method, which makes it possible to reformulate certain important mathematical objects in terms of automorphic forms, such as those studied by Braun. In our case, though, we weren’t arriving at a reformulation with the properties we needed to fully achieve our goals.” The team was trying a patchwork of methods, and none was quite getting them where they needed to be. The more Eischen tried to address this problem, the more fascinated she became with the apparent need to invoke ad hoc methods where it felt like there ought to be a more systematic approach.

“With my mathematical focus on the Rankin-Selberg method, I immediately paid attention when Selberg’s name popped up in my archival work,” Eischen says. “It was mentioned in Braun’s application to the Institute in 1963. She wrote that she was studying a connection between automorphic functions and Jordan algebras, and that Atle Selberg, Member (1947–48, 1949–51) and Professor (1951–2007) in the School of Mathematics, would be likely to have important input. Selberg rejected the application and doesn’t seem to have ever branched out into Jordan algebras.”

At the same time, Eischen continued to follow the thread of Braun’s work and learned that her collaboration with Koecher managed to use Jordan algebras to develop a uniform treatment of a wide variety of spaces on which automorphic functions are defined.

“Later, I read her correspondence with Hans Maass, a prominent mathematician, where I could trace her

moving organically from her work with Siegel to that on Hermitian modular forms to using Jordan algebras in this striking way,” Eischen says. “Encountering Braun’s perspective gave me new inspiration for how to move ahead. It’s too early to say for certain what the full impact will be on the problem my collaborators and I were stuck on, but one thing is for certain: Learning how Braun thought about various topics and linked them together has given me clarity and inspired new directions for my work.”

While the new perspectives—from decades past—have energized Eischen’s mathematical research, their significance extends well beyond individual insights, holding broader implications for the discipline as a whole.

“The human side of math is as important as the absolute truth we are pursuing,” Eischen says. “They’re profoundly connected. How we treat each other matters. How we remember and forget things matters. How we deal with contingency and grey areas and impasses matters. Ignoring the complicated reality that surrounds our work only hinders progress.”

[1] Eischen has shared her research in a lecture for the Friends of the Institute for Advanced Study and with her School of Mathematics colleagues as part of the Members Colloquium series. She has also published an article on Braun with the German Mathematical Society.

[2] Coincidentally, Creager spent time at IAS the year after teaching Eischen, as a Visitor in the School of Historical Studies (2002–03). Creager had also previously served as a Visitor in the School of Social Science (1996–97).

[3] Noether was a frequent Visitor (1933–35) to the Institute while based at Bryn Mawr College.

[4] Although he joined the Faculty in 1945, Siegel had been at IAS as a Member in the School of Mathematics since 1940.