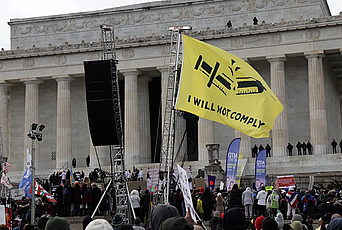

There is a uniquely U.S. story to the legal undoings following Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The American divide on abortion finds its contested space reinvigorated by the recent majority decision from the U.S. Supreme Court that overturned Roe and Casey. This distinctly American institution of politically appointed judges is unparalleled to any other top courts in other liberal democracies. Besides important debates on the constitutional order, the erosion of women’s reproductive rights, and the de-democratization of American society, the Dobbs v. Jackson case also reignites deliberations on fetal personhood. Already, states are newly engaging how to engross the fetal person. Georgia, for instance, renders the fetus tax-deductible; once doctors can detect heartbeat, fetuses are legal persons in Georgian law, making them claimable as dependents in tax returns.1 Arizona and Alabama, too, have recently passed abortion bans that define the legal personhood of the fetus. In contrast, the U.S. Supreme Court just rejected the petition to claim personhood status for a fetus after conception which was brought out of Rhode Island.2

It is notable that laws regarding fetal personhood also mushroomed following Roe itself in 1973, including inquiries regarding the status of frozen embryos.3 While these instances of reinstating fetal personhood appear mostly as an ideological side-show, uses of legal personhood reflect a more complex contending of law vis-à-vis matters of life. Our contribution here focuses less on the current contested politics behind Roe and Dobbs, and more on the question of how fetal personhood attaches to or detaches from forms of life and the contemporary biological, technological, and relational nature of reproduction. Beyond the justified outrage over the Dobbs ruling, the tension between law and life was an already existing legal affair with complex, and often unresolved, debates about the boundaries of the natural and the artificial, the social and the technological. The articulation of fetal rights brings about foundational puzzles within the domain of legal persons, deliberations on which may form opportunities to reorganize life in new ways—albeit vigilantly— including those that account for reproductive justice.

Legal Personhood: Past and Present

The topic of legal personhood is a richly debated area in legal theory and the anthropology of law. Integral to Western legal thought, the early history of legal personhood captures the inventive ways in which law deploys legal fictions to organize, resolve, or re-order social problems. Roman law, for instance, invented legal techniques of personhood to find resolutions to practical dilemmas in society and its institutions, operating primarily as a juridical placeholder to accommodate relationships with the city, estates, or kin.4

Legal personhood in Rome did not embody any reference to a natural or human person; it was not shaped according to biological understandings of human beings. Instead, the biological was adapted by law to fit the function of a person, thereby “fictionalizing biology so as to provide the necessary warrant for each of the transactional personae that it invented.”5 A good example is Roman adoption, where one could adopt adults, or could adopt grandsons to the status of sons regardless of biological order of reproduction. Scholars refer to this as artificial personhood, denoting the fictional ways personhood has been imagined. But this early iteration of legal personhood— as an invented artificial intervention—was soon to be destabilized by Christianity and the human sciences.

The concept of the natural person as attached to the human being occurred over an extended period, starting from the influence of Christianity on law in the Middle Ages and reaching through to the rise of the human and life sciences in the nineteenth century. Biology played a particularly vital role in constituting the naturalized person, illustrative in the legal assumption that natural persons are either male or female. Apart from the rudimentary facts of biology that have organized law foundationally in the realms of family and inheritance (such as birth, death, sex, and reproduction), the biological and psychological sciences helped constitute the natural person by providing scientific knowledge of humanity and human behavior. The strong influence of human rights in legal systems around the world further emphasized the legal subject’s reference as a naturalized human being.

Throughout modern history, the bio-legal configuration of personhood has functioned by means of dichotomous division—between persons and things, life and law, mind and body, human and the non-human—and the natural person in modern law tightly references the natural body, through birth and death, the division of the sexes, and metaphysical human (and liberal) traits such as autonomy, integrity, and agency6. This bounded human has received due critique from feminist scholars, who point out discrepancies of the natural person when turning to the pregnant body.7 Anthropological theory, too, subjected law’s natural person to reproach by pointing to the Eurocentric constructions of personhood, including metaphysical understandings of autonomy and bodily integrity. Rather than the bounded self, individuality in non-western societies is relational—“dividual” as the anthropologist Marilyn Strathern calls it.8 Moreover, the relational includes non-human and inanimate others, which disturb the vital modern distinction between a person and a thing.

The introduction of biomedical technologies in contemporary times has complicated disputes around personhood, particularly fetal personhood. Take, for instance, obstetric ultrasound imaging and Prenatal Genetic Diagnosis (PGD), which have become routinized in medical practice and even legally required in specific U.S. jurisdictions. Scholars have shown how requiring women to undergo ultrasound imaging make them more empathetic to the fetus, and less-inclined to carry out a planned abortion.9 On the other side, the routinization of PGD testing causes higher frequency of terminations following the diagnosis of intellectual and physical disability, prompting advocates of disability rights to resist mainstreaming such testing.

While such biomedical technologies impact society at large, they specifically influence the boundaries and limitations of fetal personhood in law. Here, juridical persons and natural persons are often collapsed, compounding not only moral claims on the fetus, but also the apparent paradoxical situation that the law allows both abortions and tort suits for pre-birth injuries.10

It is, in fact, the conceptual work of disentangling this presumed paradox that allows fetal personhood to be more than the politicized version it begets from the U.S. abortion debate. Moving beyond a pro-life/pro-choice dichotomy, personhood can be put to work to ignite its possibility and reconfigure itself to a definition more amenable to emerging forms of justice.11

Futures of Legal Personhood

Arrangements of fetal personhood in society today can be interpreted in two ways. On a political level, fetal personhood demonstrates the ideological deployment of the fetus (turning the fetus into a tax-deductible entity as a pro-life gesture). On a more legal-theoretical plane, however, it can also be seen as a demonstration of how legal forms and biological knowledge coalesce to transform legal representation (personhood) into a biological “faction” (fiction as legal fact). Beyond the issue that some states assign personhood to the fetus while others do not, a complication occurs as personhood (as biological faction) becomes attached to specific rights.

Clashes emerge once the right of the fetus is pitted against a pregnant person’s life; which rights should prevail over the other? Here, the pregnant body is not one that fits in the individual protection of human rights. The individualized concept of rights works against a body that is “multiplied”; while it invites the protection of one life (the fetus), it does so within the body of another life (of the gestator). Hence, assigning legal personhood to a fetus living inside another legal person creates a conflict between a naturalized legal personhood (the biological status of the fetus attached to the legal representational status of personhood) and the rights claims of a citizen (the state granting rights to legal persons as citizens). Deliberations over these legal problems are important in moving forward the social and political discussion around fetal personhood, and in preparing for further social and technological challenges on legal understandings of “life,” “persons,” and “birth.”

The pluralization of personhood becomes a necessity when considering biomedical technologies that determine disease and disability from the point of conception. Wrongful life claims—in which parents (or the children themselves) sue third parties for damages for a life of preventable disabilities—are proliferating in many jurisdictions. Children can now legally contest their own conception.12 Moreover, the legal status of the fetus becomes more pressing with pending technologies that allow ectogenesis: the gestation of embryos outside the uterus in artificial environments. Here, not just reproductive material, but the actual gestational process is detached from the human body, thereby bringing the body/life question central to the puzzle of fetal personhood/fetal rights.

A latent way to engage these complexities is to divert attention to potentialities enacted through “the body.” According to Strathern, the oscillation between person and thing is a core mechanism through which we actualize the body in modernity and modern law. The potentiality of personhood in the case of an embryo, for example, varies according to whether the embryo is frozen or thawed, implanted in utero or discarded.13 The body can actualize as a different “form,” according to the relation that is actualized by the claim.

Strathern notes that the question of whether body parts can be seen as property is dependent not only on biological relations (the detachment of parts from the whole), but also conceptual relations (the conceptual capacities to detach parts from wholes). We can imagine for instance that the frozen embryo (as gestationally detached from, while genetically attached to, the original biological parents), can, conceptually, be detached from the original biological parents when the embryo is donated to “intended” gestational/adoptive parents. Hence, the emergence of biomedical and reproductive technologies further complicates the biology of parts and wholes, as well as the concept of detachment—concepts which do not have a space in existing perspectives of legal personhood.14

The conception of a personhood tightly attached to nature—contrasting the varied definitions of personhood throughout history and complicated by current disputes — has caused scholars to criticize the concept for subsuming the singularity of life it purports to represent: a false technique to sustain a universalized form of human character.15 However, rather than concluding from such a critique that law subsumes life with its ominous power, exploring constructions of personhood potentially opens opportunities to articulate new avenues of thinking personhood beyond rights and interests.16

Besides resisting how the U.S. Supreme Court has overturned Roe—namely by creating new legal factions around the interpretation of the constitution—here lies a task for legal scholars and the broader public: to imagine and re-imagine the relation between law and life.

The views expressed in this opinion and analysis article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute Letter’s editorial staff.

Sonja van Wichelen is Associate Professor in Sociology with the School for Social and Political Sciences at the University of Sydney, Australia. She is a IAS Member (2020–22) in the School of Social Science. Her most recent book is Legitimating Life: Adoption in the Age of Globalization and Biotechnology (Rutgers University Press, 2019).

Marc de Leeuw is Senior Lecturer in Legal Philosophy with the Law School at the University of New South Wales, Australia. He is a IAS Visitor (2020–22) in the School of Social Science. His most recent book is Paul Ricoeur’s Renewal of Philosophical Anthropology: Vulnerability, Capability, Justice (Rowman and Littlefield, 2021).

- Ava Sasani, “Georgia Abortion Law Says a Fetus Is Tax Deductible,” The New York Times, August 4th, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/ 2022/08/04/us/georgia-abortion-law-fetus-tax-dependent.html

- Samira Asma-Sadeque, “US supreme court declines to take up fetal personhood case,” The Guardian, October 11, 2022, https://www. theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/11/us-supreme-court-fetal-personhood-appeal-case

- See Cromer, Risa. 2019. “Making the Ethnic Embryos: Enacting Race in US Embryo Adoption.” Medical Anthropology 38 (7): 603–619.

- See Mussawir, E., & Parsley, C. 2017. The law of persons today: At the margins of jurisprudence. Law and Humanities, 11(1), 44–63, p. 49.

- See Pottage, A., 2002. Unitas personae: on legal and biological self narration. Law & Literature, 14(2), pp.275–308, pp. 289–290.

- See Van Wichelen, S. and De Leeuw, M., 2022. Biolegality: How Biology and Law Redefine Sociality. Annual Review of Anthropology, 51, pp. 383–399.

- See for instance Karpin, I., 1992. Legislating the female body: reproductive technology and the reconstructed woman. Colum. J. Gender & L., 3, p.325–350.

- See Strathern, M., 1988. The gender of the gift. In The Gender of the Gift. University of California Press, p. 13.

- See Mills, C., 2018. Seeing, Feeling, Doing: Mandatory Ultrasound Laws, Empathy and Abortion. Journal of Practical Ethics, 6(2): 1–31.

- For instance, when so-called wrongful birth or wrongful life claims are invoked where medical negligence has led to the birth of an unwanted or disabled child, respectively.

- See also Gündoğdu, A., 2021. At the margins of personhood: Rethinking law and life beyond the impasses of biopolitics. Constellations, 28(4), pp. 570–587.

- Van Beers, B., 2017. The Changing Nature of Law’s Natural Person: The Impact of Emerging Technologies on the Legal Concept of the Person. German Law Journal, 18(3), pp.559–594.

- Strathern, M., 1999. Property, substance, and effect: anthropological essays on persons and things (pp. 248–260). London: Athlone Press, p. 175.

- See Esposito, R., 2015. Persons and things: from the body’s point of view. John Wiley & Sons.

- See also Esposito ibid.

- See also Vatter, M. and De Leeuw, M., 2019. Human rights, legal personhood, and the impersonality of embodied life. Law, Culture, and the Humanities, https://doi.org/10.1177/1743872119857068.