Promoting Human Rights and Democracy in China

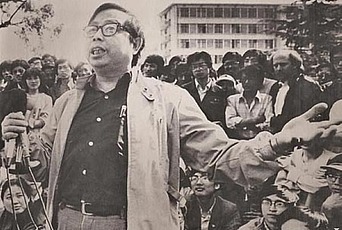

From the Chinese Revolution of 1911 to the May 19 Movement of 1957, from the Xidan Democracy Wall of 1978 to the Democracy Movement in 1989, Chinese people have never ceased in their struggle for democracy. When the Tiananmen Massacre shocked the world, I was a brainwashed high school student. It was only several years later that I realized I was a survivor of the massacre. In a speech that I gave at the June 4th Vigil in Hong Kong Victoria Park, where around 180,000 people gathered to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre in 2014, I reflected: “If I had been born two years earlier, I could have been the one overrun by tanks and my mother could have been one of the mothers who had shed all her tears but had been forbidden to speak the truth or to simply commemorate.”

In the 1990s, I was studying at Peking University, a leading university for promoting democracy and freedom since the 1910s. I had the opportunity to read some banned books and to meet a few open-minded professors. I gradually realized that I had been deceived for so many years by all of the textbooks, teachers, and Communist Party propaganda. “Think independently!”––I can still remember well how excited I was the first time I heard this sentence from an inspiring professor, but it took me much longer to realize what it meant for me to “think independently” in China. In 1992, 1994, and 1998, respectively, some dissidents tried to found oppositional parties, and hundreds of them were thrown into prison and many were imprisoned for ten years or more. Hu Shigen, a university lecturer, was sentenced to twenty years.

The Sun Zhigang case raised the curtain on the rights defense movement. Sun Zhigang, a young designer, was taken to a “Custody and Repatriation Center” and tortured to death in 2003. With two other scholars, I wrote an open letter to the National Congress to challenge the constitutionality of the Custody and Repatriation system, which was obviously unconstitutional, and to push forward the establishment of a constitutional review system in China. It was a carefully considered “open conspiracy” on our part, and we were prepared for the potential risks in making such calls. A few months later, this unconstitutional system was abolished, a result of nationwide anger and pressure. To our wildest surprise, instead of being punished, we were selected by the government as “Ten People in Rule of Law in 2003.” Honestly, I’m a little embarrassed now that there was a time when I was not ashamed of being praised by the Chinese government.

My name appeared frequently in newspapers and on television and social media. I received countless letters from all over China, asking for help. They were victims of torture, forced abortion, forced eviction, religious persecution, miscarriages of justice, corruption, pollution, contaminated milk powder, poisonous vaccines, forced labor, so on and so on. It was not possible for individuals to represent them all, so I co-founded a non-governmental organization (NGO)––the Open Constitution Initiative (GongMeng)––and it became an important platform for early promoters of the Rights Defense Movement. Lawyers, journalists, scholars, and bloggers played an active role in the rise of this movement, which uses existing laws and legal channels to defend human rights and promote rule of law in China.Why was the Rights Defense Movement able to emerge under such a suppressive regime? The development of a legal system and legal profession after the Cultural Revolution, the new space enlarged by the rise of a market economy, the internet, and social media, the dissemination of liberalism ideas and expanded consciousness of civil rights, and the tough efforts of dissidents and democracy activists since the late 1970s, all contributed to the possibilities of a new human rights movement.

Still, China continues as a party-state system, and a meaningful political reform has not occurred. Chinese authorities brutally violate human rights and oppress freedom everyday and everywhere. Unchecked power, corrupt officials, a flawed judicial system, and a huge wealth gap have produced immense injustice and grievance. The Rights Defense Movement was shaped and developed through such a social context and political institutions, and over time, has shaped and changed the social context and political institutions.

Unchecked power, corrupt officials, a flawed judicial system, and a huge wealth gap have produced immense injustice and grievance.

With a doctorate degree in law, a bar certificate, a headful of ideas about freedom, democracy, and constitutionalism deemed “reactionary” by the party doctrines, a pen that could argue and incite, and an inflated sense of self due to hype from domestic and overseas media outlets, I became active and quickly known in China’s human rights movement. I went hither and thither to represent clients in all kinds of “sensitive” cases, networking human rights lawyers and activists.

Cai Zhuohua is the pastor of a Christian “house church.” He and his family were arrested for printing the Bible and distributing it to other Christians. In 2005, I defended him, along with other lawyers, including Gao Zhisheng, who was later detained and severely tortured. When the trial began, although we did everything we could, Cai’s mother was not allowed to enter the court as a bystander. During the trial, the judge bluntly interrupted the defendant and his lawyers dozens of times. In 2006, Wang Bo and her parents were sentenced to four and five years in prison, respectively, because they were Falun Gong believers, and they disclosed their torture on the internet. Falun Gong is the most persecuted religion in China. Defending a Falun Gong case was very dangerous and few lawyers were willing to do so. But we organized a defense team of six lawyers, and in our statement of defense, we challenged the entire legal basis of suppressing Falun Gong. After the trial, four enraged court workers lifted me up by my arms and legs, carried me across the high steps, and threw me out of the court building. Since 1999, there have been more than four thousand Falun Gong practitioners who have been tortured to death in prison or secret detention centers known as “black jails.”

Chen Guangcheng is a blind activist in Shandong Province. He wanted to sue local authorities for performing brutal forced abortions and forced sterilizations. The media was prohibited to report this so he came to GongMeng to ask for help. After hearing his story, I decided to investigate the incidents and represent the victims. I documented many shocking atrocities and when I published my sixty-page report online, it aroused the attention of Chinese citizens and international media. Chen was soon detained and received an imprisonment sentence of four years and three months. I then organized a team of human rights lawyers to defend him. Nearly every lawyer connected with his defense experienced being followed, robbed, and beaten.

In addition to GongMeng, I founded China Against the Death Penalty, which was the first and only NGO dedicated to abolishing the death penalty in China. China carries out more than 80 percent of all executions in the world every year. Since a small group of human rights lawyers could not pay attention to all death penalty cases, our strategy was to focus only on the wrongful conviction cases––under China’s judiciary, many people have been sentenced to death and even executed based on fabricated evidence or coerced confessions by torture. We took more than thirty such cases, and it was extremely difficult to redress the injustice. Thanks to our persistent efforts of many years, around a dozen citizens were released from death row.

Since 2003, together with other human rights activists, I defended prisoners of conscience, owners of “nail households” who refused to sell their homes to developers, victims of torture, and victims of melamine-tainted milk formula; initiated and participated in waves of citizen signature campaigns; took part in street demonstrations and protests; and gate-crashed black jails and brainwashing classes sponsored covertly by local governments. In 2008, 303 prominent Chinese intellectuals initiated Charter 08, which was inspired by Charter 77 of Czechoslovakia, demanding human rights protections. I helped Liu Xiaobo draft the Charter and collect signatures. In the open letter, we demanded a meaningful democracy and rule of law, and the end of one-party rule. Liu was charged with “incitement of state subversion” and sentenced to eleven years. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 while in prison and died of cancer on July 13 in state custody.

After the Tibetan unrest in Lhasa in 2008, I organized an open letter, signed by twenty Chinese rights lawyers, expressing our concerns about the arrested Tibetans and offering to provide legal aid to them. GongMeng conducted an investigation in Tibetan communities and published a report the following year, providing an analysis of social reasons for the unrest. This was likely the last straw leading to my disbarment in 2008 and GongMeng’s shutdown in 2009.

Still we didn’t stop and went even further. We promoted the New Citizens’ Movement in 2012 when Xu Zhiyong published his article calling for a nationwide movement of active citizenship. He outlined the tactics to be employed: “repost messages, file lawsuits, photograph everyday injustices, wear t-shirts with slogans, witness everyday events, participate or openly refuse to participate in elections, hold gatherings or marches or demonstrations, do performance art, and use other methods in order to jointly promote citizens’ rights movements and citizens’ non-cooperation campaigns—such as assets reporting, openness of information, opposition to corruption, opposition to housing registration stratification, freedom of beliefs, freedom of speech, and the right of election.” “Practice the New Citizen Spirit in action. Citizens’ power grows in the citizens’ movement.” The New Citizens’ Movement included such activities as demanding the disclosure of official wealth, equal rights for education, and joint citizen meals (or same-city dinner gatherings). The article, with its clear political message advocating for trans-regional organization and street activism, brought the rights defense movement to a new level. Xu, my co-author of the open petition in Sun Zhigang’s case, a co-founder of GongMeng, and an unstoppable activist, was recently released from a four-year imprisonment in a Beijing prison.

It was amazing that the human rights movement developed vigorously and became more and more powerful in a tight corner of the repressive regime. Unsurprisingly, not long after the emergence of the rights defense movement, the Chinese government saw it as a real threat to the political system and never stopped its harassment and crackdown on rights activists and NGOs. The government adopted a flexible and comprehensive strategy, from oral warnings, disbarments, house arrests, travel bans, criminal charges, labor camps, and public humiliation to abduction, torture, and collective punishment. Every day reports came from all over China that human rights defenders were disappearing or jailed.

Because of my human rights work, I was disbarred, banned from teaching, fired, kidnapped, disappeared, and detained and tortured by secret police. I once briefly described the “badge of honor” I earned bit by bit:

First, they came to me speaking softly: “Look, you have knowledge, fame, and opportunities. Why mix with those people? You will enjoy many benefits if you side with the party.” I didn’t listen. I continued.

Then came the warnings: “It’s very dangerous if you continue. Take our advice, you’ll have a full belly. There will be consequences for giving trouble to the government. Don’t you see? Professional promotions, research funding, awards, you get none.” I didn’t listen. I kept going.

Then they began to dress me down. They confiscated my passport, so that I wouldn’t have a chance to experience the sufferings of life overseas. I didn’t listen. I kept going.

Then they disbarred me. The Chairman of the Beijing Lawyers’ Association Li Dajin and the chiefs at the Beijing Bureau of Justice hissed: “We must find ways to smash the rice bowls of these lawyers.” I didn’t listen. I kept going.

Then they closed down my blogs, my Weibo accounts, and my reincarnated Weibo accounts. I was barred from media interviews and college lectures. Upon swiping my ID, the screen would display “key stability maintenance target.” Some of the people who knew me wouldn’t dare to dine with me or even call me anymore. I didn’t care. I kept going.

Then they used thugs to follow me and attack me when I was away from home working on cases. Around the country’s sensitive dates, regular or circumstantial, I would be placed under house arrest by the domestic security police, or taken to travel in their company as they attempted patiently to give me their political persuasions. I was obstinate, sinking only further and deeper.

Then, to save me, they used kidnapping. In the middle of the night, they covered me in a black hood, handcuffed me, and threw me in a little black car, took me to a black jail, and locked me in a little black room for two days and two nights. They threatened to throw me in jail for inciting subversion of state power. I didn’t repent. Instead, I wrote articles, acted as a citizen deputy in case after case and organized NGOs to assault the socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics. If I stopped at any given point, repented, reinvented myself, I could still have had a great future.

The Jasmine flowers blossomed quietly in the early spring of 2011, and the troublemakers were all rounded up. (During the Jasmine Revolution of the Arab Spring, an anonymous call for a “jasmine demonstration in China” was posted and spread on Twitter and other social media. Hundreds of lawyers, activists, and bloggers were kidnapped and disappeared.) Their education of me also escalated. Again, in a black night, with a black hood, handcuffed, in a black car, thugs kidnapped me and threw me in a black jail, this time adding fists and face slapping. No communications with the outside world, no sleeping, no receiving information, no freedom to stretch my arms or legs. During my seventy days in detention, I wore handcuffs twenty-four hours a day for thirty-six days and was forced to stay in one position, facing a wall, for eighteen hours straight for fifty-seven days. Physically and mentally tortured, I began to write statements of repentance and statements of guarantee. I had to rewrite them over and over to improve my sincerity. Never so profoundly did I experience the superpower of “the people’s democratic dictatorship.”

They had known all along, it turned out, the thing that I feared under the surface of bravery. They knew it from the very beginning and I should have known.

I feared for the people I love. Once my wife and daughter were hurt and faced with more threats, I was immediately caught in a dilemma. “Are you a responsible man or not?” In an irresponsible system, for a person wanting to be responsible, family responsibilities and social (historic) responsibilities are in direct conflict with one another. If you end up in prison, you will not be able to take care of your family; but to walk this path that I do, you will inevitably end up in jail or alternatives of jail. Away from this path, you may fulfill your family obligations, but you not only have to abandon your ideals, your children will continue to live in the same irresponsible system, and they too in the future will face the choice between family obligations and social responsibilities. Not to mention that it’s irresponsible to leave what we ought to be doing to the next generation.

Lawyers, dissidents, citizen journalists, NGO activists, and rights defenders have been continuously subjected to harassment and persecution. Some activists have even lost their lives. Liu Xiaobo, Li Wangyang, Cao Shunli, Zhang Liumao, Xue Jinbo, among other human rights defenders, have died in custody because of proven or believed torture and ill treatment. But for various reasons, activists have not been silenced by harassment and slight punishment, like warnings, disbarment, house arrest, or even abduction and short-term detention. For many, the more persecution they encounter, the more solidarity they feel with like-minded people and the more valuable they believe their work to be.

Since Xi Jinping assumed power in late 2012, he has been trying to change the methods used for cracking down on the rights defense movement, seemingly from “stability maintenance” to “wiping out.” Before, the goal was primarily to punish those who crossed the line and to retain the advantages of strong stability maintenance. However, the goal of Xi is simultaneously to eliminate the nodes of civil mobilization, eradicate emerging civil leaders, and disperse the capacity for civil resistance. At a minimum, the authorities want to curb the momentum in which the rights defense movement has been steadily growing and flourishing.

The well-known “709 crackdown” shocked the Chinese and the world. It was the worst crackdown on human rights lawyers since the recovery of the judicial system in the late 1970s. At around 3 a.m. on July 9, 2015, the human rights lawyer Wang Yu was abducted from her home in Beijing. Her husband, rights defender Bao Longjun, also disappeared. Wang is renowned in China. She represented Cao Shunli, who died after being denied medical treatment while in custody for her human rights activism; Ilham Tohti, a Uighur scholar unjustly sentenced to life in prison; and well-known protest organizer Wu Gan. In the days after Wang’s arrest, dozens of human rights lawyers were abducted, arrested, and disappeared; as of May 2017, in twenty-four provinces in China, at least 320 lawyers, law firm staff, human right activists, and family members have been questioned, summoned, forbidden to leave the country, held under house arrest and residential surveillance, criminally detained, arrested, or gone missing. All activists detained in the 709 crackdown were brutally tortured; in custody, most were forced to take unidentified medicines that are mentally and physically harmful.

But isn’t there a profound dread lurking behind this barbarism?

On the one hand, the Communist Party is not as confident as it seems to be. It is facing deep crisis politically, economically, socially, and ideologically. It has an exaggerated fear of opposition, resistance, and social-political movement. On the other hand, the development of the rights defense movement has experienced at least four trends since its rising, namely, organization, street activism, politicization, and internationalization. These trends can be seen as the amazing achievements of the rights defense movement, as well as the deep reason for the government crackdown on this movement.

Before and even since the rise of the rights defense movement, people have not abandoned efforts toward organized protest, as illustrated by the creation of political parties such as the Chinese Liberal Democratic Party and the China Democracy Party, and groups such as the Tiananmen Mothers, the Pan-Blue Alliance, the Guizhou Human Rights Forum, Charter 08, various house-churches, and rights NGOs. Mobilization and organization in the internet age have allowed for collective action and social movements without organizational structure, charters, leaders, or fixed membership. “Organizing without organization” obviously reduced the costs and the risks of setting up an underground political organization or a formal organization.

With the understanding that judicial independence does not exist, especially in human rights cases (sensitive cases), rights lawyers have had to resort to activism outside the courtroom and in the street, aiming to pressure the court, the government, and decision makers behind the scenes.

The rights defense movement is the practice of the theory of human rights and liberalism and democracy. As liberal democracy became a political-social aim of some influential intellectuals and as more and more people moved out of the shadow of brainwashing propaganda and into civil consciousness, there has been a tremendous momentum to bring human rights, liberalism, and democratic ideas into practice. The struggle for the right to vote and freedom of speech, assembly, demonstration, and association should be an intrinsic part of a human rights movement, and it has been so in China. The initial idea of the Rights Defense Movement was to use existing laws to defend human rights and freedom; however, the more rights lawyers use these laws, the more they feel the need to go beneath the surface and change the underlying policies, institutions, and system.

Wherever or whenever human dignity prevails, tyranny is defeated.

I am optimistic that Chinese people will in the future enjoy a liberal democracy and rule of law because the pursuit of human dignity and freedom is undefeatable. I was tortured every day during my detention in an unknown black jail in 2011––the guards were ordered not to open the windows and curtains. But a guard opened the windows for me a couple of times. Once he even took me out of my cell, letting me breathe fresh air. Wherever or whenever human dignity prevails, tyranny is defeated. The Chinese Communist Party has been acting against human nature and that is why we have sacrificed so much to fight against the Communist Party. I am honored that my courage, my struggle, my suffering have been a small part of that great cause.