The Shiite Interpretation of the Status of Women

The status of “women” as interpreted by Shiites in a philosophical and legal context, as well as their social status in Shiite communities, throughout history up until today, can only be considered and studied within a general framework, using an approach that must obviously be based on the legal foundation established by religious Islamic thinking. Nevertheless, there are obvious differences between what is understood as Shiite philosophy and religious prescription and what is actually practiced in a social context within Shiite communities.

Those differences are not only due to and justified by theological or legal issues, but various sociohistorical contexts have also played a major role in their development. The important fact that, for at least a few centuries, Shiites have mainly settled in Iran leads us to the conclusion that basic (even pre-Islamic) culture and Iranian civilization are the most important influences on Shiite beliefs, its concepts, its religious beliefs, and its legal and sociopolitical philosophies, whereas the great majority of Muslims—in other words, religious schools and theological doctrines—are affiliated with the Sunni community and are generally present in all Arab countries, Turkey, and in the Far East, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Naturally, a major issue such as the role of “women” and “the social status of women” in society can be directly influenced by the social and political environment as well as local traditions and beliefs. The main factors in this regard are: the contribution of religious beliefs and national folklore as well as local literature and the collective conscience of a nation, including the epic history of a nation as told in prose or verse and popular stories that have had an important direct impact on behavior and traditions throughout history.

According to the Qurʾān, women (at least in terms of their relationship with God and their responsibilities) are equal to men. Women have the same obligations as men when it comes to a belief in God, worship, and the practice of certain religious rituals such as prayer. Women are born just like men, according to divine nature. If Eve—as the first woman—was misled by Satan, her fault is equal to that of Adam—as the first man—and not superior. Thus, she is not the symbol of fault or “original sin.” Overall, the original religious texts describe women in Islam as innocent and pure beings who cannot be more tempted by Satan than men.

Insofar as exclusively religious rituals are concerned, Muslim women and men have the same obligations. However, this equality is challenged when it comes to civil rights, where women and men are not equal with regard to rights and responsibilities according to the Qurʾān and the religious teachings of Islam. Here, the differences between the Shiite and Sunni interpretation of jurisprudence (fiqh; religious law) create this divergence. Shiite thinking provides a constant and dynamic aspect to ijtihad (personal interpretation of the religious texts in order to adapt them to new situations) and to the renewal of religious fatwas that must be followed at all times by the fuqaha (legal scholars).

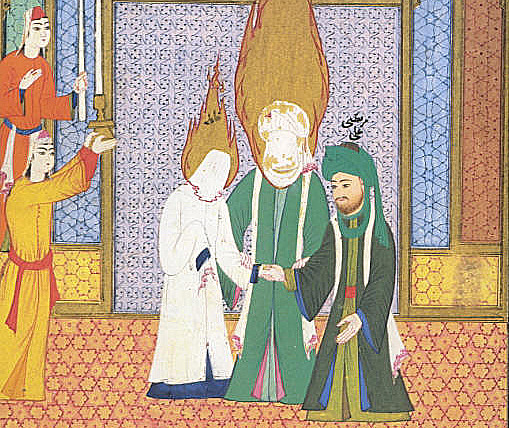

Of course, women have an important role in Shiite religion; the generation of the prophet of Islam can only continue through his daughter Fatima. The latter is not only the prophet’s daughter, but she is also the mother of the Shiite Imams. She transfers the prophet’s legacy to the Shiite Imams, their sons, and all future generations. Fatima’s predominance as the wife of Ali b. Abi Talib—the prophet’s cousin—her son-in-law, and first Shiite Imam takes on divine proportions. This image of Fatima that the prophet transferred to the Shiites is represented with tremendous honor and respect in Shiite writings and traditions. This is an important contribution to the role of women in the collective memory and in Shiite tradition. In certain Shiite traditions, she is represented as the one who transmits the prophet’s enlightenment and soul to the prophet’s children and the Imams. She is a commentator on the Qurʾān, her divine knowledge giving her scientific expertise that is comparable to that of the Imams. Thus, the fact that she is a woman does not prevent the Shiite from considering her as a divine reference in Shiite religion, a reference that not only embodies divine purity and justice as well as eternal enlightenment, but also presents her as the teacher and divine guide of the Islamic umma. Fatima is always a role model in the Shiite community. The role model that she represents is not limited to her knowledge; she also has a dominant role as the wife of Imam Ali, the prophet’s successor, and she is the defender of his succession (contested by the Caliphs). The teachings of Ali b.Abi Talib, which later become the guide for all Shiite Imams, owe a lot to his wife’s spiritual influence. Such a status is neither introduced nor authorized for any woman in Sunni tradition, a doctrine that is completely different from that of the Shiites. And that has had its repercussions in Sunni thinking and actions with regard to this issue throughout history.

Aïcha, the prophet’s wife and the daughter of the first Caliph, is—contrary to Shiite tradition the favorite and predominant female figure in Sunni religion; she is mentioned as a narrator and a source of shari’a and jurisprudence, but her status has nothing to do with that of Fatima. The latter’s daughter, Zaynab, also plays an important role. She was present at the side of Husayn b. Ali, the third Shiite Imam, at the battle of Karbala and thus embodies a crucial contribution to the heroic legacy and religious beliefs of the Shiites. Her tomb is worshipped with fervor by the Shiites in Damascus. After the tragic events surrounding the assassination of her brother Husayn by a Caliph among the Umayyad in Karbala, she took over and assumed the responsibility for her family, and even for her brother, the next Imam, and for the transmission of the political and religious message of this movement. Other women of the prophet’s family also represent the status of women and its importance in Shiite thinking. Among them is Fatima Masumeh, the daughter of Musa b. Ja’far, the seventh Imam among the Twelve Imams. Her shrine in Qom is the reason that this city exists as one of the main centers of Shiite power and authority throughout history. Even in the Islamic Republic of Iran, where shari’a is the foundation of the constitution, even though Fatima and Zaynab shape the religious image of women in Shiite society and tradition, and despite the importance of the veil, which has become a condition and law to be respected by all women, the social and political role of women has grown in importance since the beginning of the Islamic revolution. This has opened up a way for women to become more active participants in Iranian society where the majority is Shiite.

Women’s participation in society is not limited to social and political activities; they also play a much larger role in universities and other educational and professional institutions than women in other Muslim countries, or even in Iran before the revolution, where globalization had resulted in an increased presence of women in every sector. Of course, this development had its own consequences in Iran as a Shiite country compared with many other Muslim countries. During the last thirty-five years, Iranian women have become more and more demanding. Literacy among women has increased at a moderate pace, which has allowed them to become familiar with various aspects of modern life. Today, women’s expectations have turned into demands for civil rights, which is of course a big challenge for the Islamic Republic. The presence of women in elections and government positions, such as the parliament and local councils, as well as their participation in different ministerial functions are notable examples.

However, the result of these developments is not limited to this. Women play an active role in newspapers and media, and feminist movements are on the rise. All of these factors combined have applied pressure to modify or weaken several of the strict laws of shari’a concerning women in areas of society such as marriage, divorce, succession, and specific legal questions concerning women and the inequality of women.

Besides the increase of the scientific level in women’s education and the importance of their demands for equal rights, traditional women have also penetrated the religious schools in cities such as Qom and Teheran. The religious education of women in Muslim tradition goes back to early Islam, but this Shiite tradition originates with Fatima, a role model for Iranian women. Having participated in religious education and being familiar with the fundamentals of religion and theology, women have made a brave attempt to resolve many legal problems that are based on shari’a and were adopted by the parliament of the Islamic Republic. In this context, the movement of religious modernism, which has seen most of its growth since the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, focuses in particular on the issue of women with regard to the necessary changes in the legal system. The subject of women has thus become an issue that must be revealed in the sources of Islamic thought and tradition in order to be able to come to a modern interpretation that is in line with human rights. Today, a new interpretation of women’s rights and other issues related to women is becoming a challenge for the religious modernists.

Shiite thought has at least the potential advantage to create the foundation for the revision of the status of women and women’s rights in Islamic jurisprudence. However, Shiite legal scholars are still conflicted by conservative thinking, and many reformists consider the status of women in Islamic society to be a great challenge to the interpretation of shari’a and its modernization in order to protect women’s rights and modify religious laws relating to women. For example, certain modern Shiite thinkers currently oppose the obligation of women to cover their heads. The overall attitude of Iranian society in this regard is very different from that of other Muslim countries. Young women, especially, have decided to wear their head cover in a completely different way than prescribed by the strict Muslim dress code. They wear it in a variety of colors, shapes, and fashions, which in itself represents creative diversity and is setting new role models and beauty standards. This is a strictly Iranian phenomenon that has attracted much attention from abroad. Wearing a burqa and having to cover the eyes and face are considered very shocking concepts in Iranian society, contrary to many other Muslim countries where it seems that the Salafists who adhere to Sunni tradition have applied more pressure than ever to impose their opinion on the status of women in Islamic society.

Shiite philosophy considers that renewal in ijtihad and in fiqh is always possible, and it acknowledges this as one of its main points and differences from Sunni jurisprudence. Morteza Motahhari, the famous ideologue of the Islamic Republic, has dedicated part of his religious activity to women’s issues in Muslim society, including giving his opinion on the veil, which is new and relatively speaking much more permissive—he does not see the necessity of wearing the burqa or covering the hands.

One of the problems of Islamic jurisprudence is based on the influence of patriarchy, which in turn was influenced by different social traditions throughout the history of Islam. Insofar as the issue of heritage is concerned, it is very well known that this is a case of inequality between men and women in Islamic jurisprudence, but there have been efforts in Iran to resolve at least parts of this inequality. Of course, this goes back to Shiite teachings and to the role and status of Fatima in the transmission of her father’s heritage, where—contrary to Sunni jurisprudence on heritage, which is more patriarchal—women’s rights are supported, which is the case with regard to heritage.

The Shiite fuqaha are able and many of them are willing to express their opinion with regard to the modern status of women. This surfaces with the radical opposition of Shiites against Salafists, but there are still many questions regarding women’s rights that must be resolved in the Islamic fiqh. It is crucial to consider these issues carefully and to find solutions to modernize Islam’s teachings in order to prevent the Salafist movements, which arise among the majority of Muslim countries, from becoming more powerful.