Joseph Conrad as Maestro

On an autumn night at the Institute, a sold-out audience gathered in Wolfensohn Hall for the latest evolution of an unlikely addition to the cultural canon—an opera based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The librettist, London artist Tom Phillips (a perennial Director’s Visitor, he is due to return in the fall), introduced the performance by offering interpretative outtakes from his umpteen readings of the classic novella, published in 1902.

The first time he read it, as a teenager in the 1950s, Phillips came to the same conclusion his son reached after reading the book: “Nothing happens.” The second time he picked it up, Phillips was trekking across the Kalahari Desert, turning pages by the light of campfire. For the fifth reading, he borrowed a girlfriend’s copy and marked up the margins with notes. “It spoke,” he said. “Bits kept screaming out in a special way: ‘I’m a libretto! I’m a libretto! I’m a libretto!’” Phillips obediently wrote down this libretto, using only words from the original text and Conrad’s Congo Diary. “It is lifted straight from the Conrad,” he said.

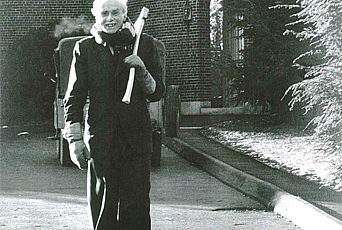

On special occasions like these, Phillips likes to wear two pashminas, in Oxford and “shrill Brazil” blues, artfully draped at the neck—not exactly the standard kit for someone who is also a zealous ping-pong player (Salman Rushdie is a longtime opponent, a “sloppy” player whom he almost always manages to defeat; at the Institute the only individual to beat Phillips is employee Herman Joachim). His collaborator is a “top-tip” composer, the sartorially snappy Tarik O’Regan, favoring cashmere overcoats and herringbone trousers. At thirty, he is a two-time British Composer Award winner.

Before raising the curtain on their opera—in one act comprising twenty-four scenes, running an hour and fourteen minutes, no intermission—the maestros encouraged the audience to watch and listen with a critic’s senses. The feedback, both at the Institute and during another workshop at American Opera Projects in Brooklyn, would help in preparations for the full-scale production, slated for 2009 (“There is already a fight for it,” said Phillips).

“If you fall asleep for ten minutes, please tell us where,” O’Regan advised. “If you fall asleep for an hour, don’t bother.”

O’Regan’s score roused a visceral response, the main theme of lower octave melodies leavened with passages of “pulsing polytonality” à la Philip Glass. He acknowledged his main influence was the British composer Benjamin Britten (Turn of the Screw; Rape of Lucretia), who in the 1940s popularized the form of chamber opera—an opera of reduced instrumental forces meant to accommodate the desire for works that could easily be toured and quickly mounted in small spaces. O’Regan composed the Heart of Darkness for eight singers and a thirteen-piece orchestra, though for the workshops the only instrumentation was a SUV sized Model D Steinway. And there were no costumes or sets; the cast conveyed the story with expressive yet measured dramatizations, as well as the odd prop: a flask, a pack of tobacco, a diary, a letter. Backstage, the singers were popping Oreos to keep their sugar levels up.

Put the prospect of Heart of Darkness, The Opera to a wellread class of readers and inevitably someone will burst into song, offering the book’s most famous and operatic line in mock booming bass: “The horror! The horror!” But otherwise, this intensely interior and highly symbolic novel—chronicling Marlow’s psychological journey during a steamboat journey up the Congo River—is not obvious opera material. In 1938, Orson Welles mounted it as a radio play, and had designs on a screen adaptation for his Hollywood debut, but his producers nixed the idea after reading the costly and politicized script. Then, in 1979, came Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, an epic production during which the director nearly lost his wife, his mind, and on three occasions threatened to take his life. But the work had never been set to music and sung. “Conrad himself said Heart of Darkness is a musical thing,” noted Phillips, citing for corroboration the author’s own remarks in the preface to the 1917 edition: “It was like another art altogether,” observed Conrad. “That somber theme had to be given a sinister resonance, a tonality of its own, a continued vibration that, I hoped, would hang in the air and dwell on the ear after the last note had been struck.” Conrad, Phillips felt, would approve.