The Exploits of Maqāma

Although the maqāma is less familiar to Western readers than the fantastic tales of the Arabian Nights, which achieved their prominence as a result of Antoine Galland’s eighteenth-century French translation, the maqāma was long central to Arabic and Middle Eastern literatures and is one of the longest traveling and widest circulating of premodern literary forms.

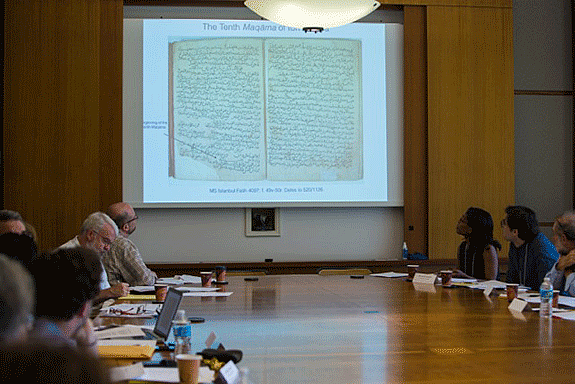

The picaresque maqāma tales were the subject of a workshop, The Maqāma and Its Readers, that I organized last May with Sabine Schmidtke, Professor in the School of Historical Studies. The workshop, generously supported with funds from New York University Abu Dhabi, brought together scholars of Arabic and Hebrew literatures.

Invented in the tenth century in Central Asia, maqāmas are collections of rhymed prose tales that recount the exploits of tricksters who travel throughout the major cities of the Muslim world and beyond. Each tale follows a similar pattern in which a narrator recounts his entrance into a new city where he goes to a particular space (a market, a mosque, a hospital). There, he asks the audience for money. The narrative reaches a climax when the narrator and/or audience recognize the individual as the notorious rogue and the two depart only to meet one another again in a different locale. The genre celebrates the boundless creativity of the author’s inventions, as each maqāma invites readers to use their own reason, knowledge, and experience to uncover the rogue’s latest plot.

Over the course of nearly a millennium, authors composed hundreds or possibly even thousands of maqāma works and collections in Arabic in nearly every major region of the Muslim world from West Africa to China. Writers in Persian, Hebrew, Syriac, and Ottoman directly borrowed themes and forms when composing their own maqāma works. Early modern Spanish novels such as the La Vida de Lazarillo de Tormes (1554) and Cervantes’ Don Quijote (1605) owe some inspiration to the maqāma. Similarly, the first Arabic novels of the late nineteenth-century renaissance of Arabic literature, Aḥmad Fāris al-Shidyāq’s Leg over Leg and Muḥammad al-Muwayliḥī’s What ‘Īsā b. Hishām Told Us, or A Period of Time signal their debts to the maqāma genre.

Conference participants presented papers on the history, circulation and interpretation of the maqāma. The morning papers began with a paper by Bilal Orfali (American University of Beirut) who discussed the Maqāma of Mosul by al-Hamadhānī, which features a seriocomic portrayal of a trickster prophet who raises a dead man back to life. This was followed by a paper I devoted to the ways that the earliest maqāma writers interpreted the work of the progenitor of the genre, al-Hamadhānī. This was followed by a presentation by Matthew Keegan (New York University) who discussed early commentaries on the text of the twelfth-century author al-Ḥarīrī whose collection of fifty maqāmāt were believed by many to be the pinnacle of Arabic literary eloquence. Devin Stewart (Emory University) presented a paper discussing the “Anti-Shi‘ism” in the maqāmāt which he discussed with IAS Member Hassan Ansari.

The next two papers of the workshop were devoted to the tradition of maqāma writing in Hebrew, represented by the thirteenth-century Judah al-Ḥarīzī who translated and authored maqāmāt in Hebrew. Jonathan Decter (Brandeis University) discussed the peculiarities of al-Ḥarīzī as a bilingual author conscious of both the Hebrew and Arabic traditions. Raymond Scheindlin (Jewish Theological Seminary) discussed the curious absence and presence of religious themes throughout al-Ḥarīzī’s collection of maqāma works. The day was ably concluded by Orit Bashkin (University of Chicago) who discussed “post-Andalusi” maqāmāt and the image of the Other found therein.