Quantum, Broadly Considered

Speaker Series

2025 was a year of heightened global attention around quantum science. To mark a centenary of modern quantum mechanics, the United Nations designated it the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology. Initiatives such as World Quantum Day underscored the field’s continued prominence in public discourse, policy, and investment.

Against this backdrop, during the 2025-2026 academic year, the Institute for Advanced Study's Schools jointly hosted organized a speaker series, QUANTUM, BROADLY CONSIDERED, hosted by the Science, Technology, and Social Values Lab. This Institute-wide initiative sought to foster scholarly dialogue on the present moment in quantum research, a moment defined by both deep theoretical uncertainty and intensifying strategic interest, exploring this issues through multidisciplinary perspectives, including at the intersection of quantum science, mathematics, technology policy, and the history of science.

The series considered not merely when commercially useful quantum technologies might arrive, but more pointedly:

- Why quantum computing has been framed as inevitable

- What stands in the way of its realization

- How scientific, political, and social systems continue to shape the trajectory of quantum mechanics, quantum information science, and quantum computing

Narratives of Inevitability: History, Funding, and Power

The opening lecture by Professor Susannah E. Glickman established a critical foundation for the series by reframing quantum technology as a historical and ideological construct, not merely a technical one. Quantum computing, she argued, did not rise to prominence solely because of intrinsic scientific promise, but rather through deliberate narrative work— particularly during the Cold War, when physicists faced both intellectual uncertainty and declining public legitimacy.

In the 1960s and 1970s, fundamental questions raised by quantum mechanics coincided with political and economic crises, including deep funding cuts following the Vietnam War. In response, physicists sought to reposition their work as essential to economic growth and national strength. Quantum computing, futuristic and perpetually “just out of reach,” proved an ideal focal point.

Glickman’s central concern was not exaggeration but rather control of narrative. When scientists and technologists control the narratives of both the future and the history of their fields, any claims about inevitability risk being self-fulfilling. Funding flows toward promised outcomes, while alternative technological paths fade from view. With reference to influential American scientists and engineers, including John Wheeler and Gordon Moore, Glickman illustrated how ideas about destiny, progress, and scale—whether philosophical or commercial—continue to shape the way emerging technologies are justified today.

Glickman challenged scholars to consider the consequences of this self-fulfilling narrative-funding loop. When policymakers act on stories rather than capabilities, she warned, the gap between expectation and reality can widen. The discussion that followed raised a difficult possibility: that even recognizing this dynamic may not be sufficient to disrupt it. Glickman's lecture framed quantum computing not only as a technical challenge, but as a case study in how scientific authority, ideology, and power intersect.

Engineering Reality: Promise, Constraints, and Time

Where Glickman interrogated the stories told about quantum computing, the lecture, by Professor William D. Oliver, confronted the realities of building and delivering it. Speaking from an engineer’s perspective, Oliver emphasized that while the theoretical foundations of quantum computing are well established, the path to practical utility remains long and uncertain.

Oliver traced the field’s evolution from quantum 1.0, where quantum effects enabled transistors, lasers, and modern electronics, to quantum 2.0, in which superposition and entanglement are harnessed directly. This shift enables extraordinary possibilities, but it also introduces fragility. Quantum states are acutely sensitive to their environment; maintaining coherence across large systems remains a formidable challenge, Oliver said.

A recurring theme in this lecture was specificity. For quantum computing to offer real value, three conditions must align: the absence of an efficient classical solution; the existence of a fast quantum algorithm; and meaningful commercial or societal payoff. Oliver noted that discussions too often focus on theoretical speed-ups without grappling with data loading, system integration, or operational context.

Error correction emerged as the most significant barrier. While there have been important milestones recently—including Google’s demonstration that increasing qubit numbers can reduce logical error rates—Oliver warned that scaling from such demonstrations to fault-tolerant machines presents significant engineering challenges and will require substantial resources. Achieving logical qubits (capable of behaving like a single, stable qubit, but at scale) demands teams of physical qubits, sophisticated control, and extensive infrastructure, he explained.

Oliver suggested that classical computing systems would not give way to quantum, but rather that quantum computers will function as specialized co-processors. But he also warned of the risk of a “quantum winter” (a risk to continued funding) if expectations continue to outrun deliverables. The ensuing discussion returned repeatedly to funding and time horizons, highlighting the tension between engineering lead times and short-term institutional pressure.

Coordination, Policy, and the Long View

The lecture delivered by Dr. Charles Tahan, widened the frame to encompass policy, coordination, and institutional design. Drawing on his own direct experience from a career spanning academia, government, and industry, Tahan emphasized that the difficulty of quantum computing is not only technical, but also organizational.

He traced modern quantum investment to Shor’s algorithm and its implications for cryptography, which catalyzed government attention around 2000. Since then, progress has depended on the deliberate construction of ecosystems: benchmarking standards; shared fabrication facilities; and communities capable of comparing disparate approaches. Tahan’s account of nurturing such ecosystems underscored the reality that scientific fields do not simply emerge, but are built.

Tahan also highlighted the scale of what remains unresolved. Bridging the gap between today’s thousand-qubit systems and the millions of high-quality qubits required for useful applications remains daunting, he observed. He noted that the “wiring problem” (the physical challenge of controlling and reading out ever-larger numbers of qubits also raised by Professor Oliver) is among the constraints that are unique to quantum computing. Rather than brute-force scaling, Tahan emphasized the need for architectural creativity: making impossible trade-offs manageable through design, as embodied by approaches such as dual-rail encoding or the development of radically smaller superconducting qubits.

Policy, in this context, should be an enabling force. Coordinated investment, workforce development, and post-quantum cryptography mandates (official requirements to transition to new encryption methods) will all shape the field’s trajectory. Significant progress also demands that the US remains open to global collaboration, Tahan stressed.

Taking Stock and Moving Forward

The QUANTUM, BROADLY CONSIDERED speaker series combined historical critique, engineering realism, and policy experience, revealing quantum computing to be both scientifically grounded yet shaped in its development and direction by its perceived value over time. Rather than offering answers, the lecture series sharpened the questions that need to be posed, from the role of narrative to the engineering and commercial challenges that remain. It invited the IAS community to sit with tension: between promise and patience; ambition and humility; theoretical certainty and uncertain practice. A further takeaway is that, still today, quantum investment decisions are based on more complex values than simply expectations of return. In the US, those values include America’s competitiveness globally and future national security.

In a pivotal year for quantum science, the QUANTUM, BROADLY CONSIDERED series created space for intellectual exploration. Rather than questioning simply whether quantum computing will succeed, it asked what kind of future is being built in its name, who will shape that future, and how responsibly society is (or should be) navigating the long path between possibility and practice—open research questions that need to be taken up by scientists, social scientists, and humanists. In this way, it reminded participants that the most important work around quantum does not lie solely in the laboratory but, just as significantly, in the way its story is told, tested, and governed over time.

###

Fall 2025

Image

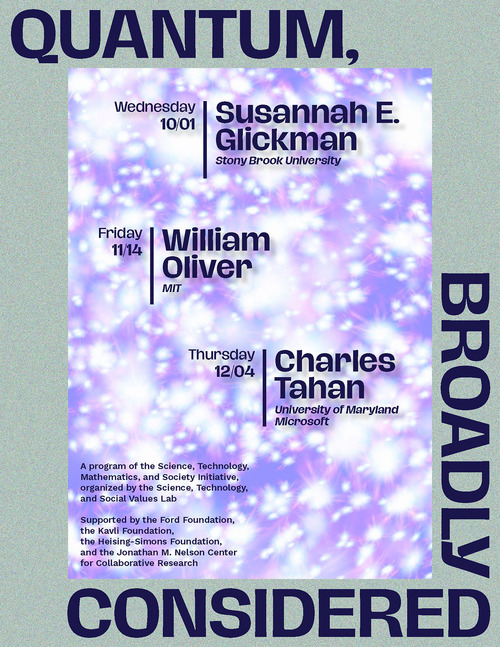

“'Philosophy is too Important to be Left to the Philosophers': On Cold War Crises and Quantum Technologies," Susannah Glickman, Assistant Professor of History, Stony Brook University

Read More

"Realizing the Promise of Quantum Computation," William D. Oliver, Henry Ellis Warren (1894) Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Professor of Physics, and Director of the Center for Quantum Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Read More

"Quantum Information Technology and Society from 2000 to 2040,” Charles Tahan, Partner at Microsoft Quantum; formerly Assistant Director for Quantum Information Science at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy

QUANTUM, BROADLY CONSIDERED is a speaker series organized by the Science, Technology, and Social Values Lab. Led by Professor Alondra Nelson, the ST&SV Lab explores emerging scientific and technological phenomena and their intersections with the frustration and fulfillment of civil, political, and social rights. It develops multidisciplinary research projects and initiatives that examine and assess scientific and technological developments and practices and their implications for matters of justice and democracy.

The QUANTUM, BROADLY CONSIDERED speaker series is a program of the Science, Technology, Mathematics, and Society Initiative, established in 2021 by Professors Didier Fassin, Helmut Hofer, Myles Jackson, Nathan Seiberg, and Akshay Venkatesh to foster dialogue across the Institute's Schools. The initiative encourages scholarly discourse on the complex and evolving relationships among science, technology, mathematics, and culture. Drawing from diverse disciplines, participants explore how scientific and mathematical knowledge intersects with social, ethical, and cultural contexts. Topics of inquiry include the ethics and safety of AI and machine learning, the creation, confirmation, and falsification of mathematical proofs, how scientific and mathematical theories are modified through public reception, forms of scientific and mathematical knowledge communication, the implications of quantum information science for research, geopolitics, and political economy, the role of intellectual property in shaping molecular biology research, the relationship between experiment and theory across physics subdisciplines, and the role of scientific expertise in public understanding of science.

QUANTUM, BROADLY CONSIDERED was organized with the support of the Ford Foundation, the Kavli Foundation, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Jonathan M. Nelson Center for Collaborative Research at IAS, and the Rita Allen Foundation.