AI and Geopolitics

Collaborators:

Tatiana Carayannis

Alondra Nelson

Marie-Therese Png

The current development and deployment of artificial intelligence presents a fundamental challenge to existing global governance structures and democratic accountability mechanisms. As claims about AI and contests over AI applications reshape strategic competition, trade relations, and diplomatic frameworks, critical questions emerge about how nations, institutions, industries, and communities can effectively govern technologies that transcend traditional geographic and regulatory boundaries. The concentration of AI development within private sector entities creates unprecedented challenges for public oversight and democratic control over technologies with wide-ranging commercial, military, and civic applications. This shift toward privatized technological capability raises urgent concerns about sovereignty, security, and equitable access to innovation, while the global contest over AI standards and supply chains are transforming frameworks for international cooperation and accountability. What governance mechanisms are needed to address the gap between the global scale of AI's impact and the capacity of existing institutions to regulate, oversee, and direct technological development toward socially beneficial outcomes?

The Geopolitics of Critical Minerals and the AI Supply Chain

The project investigates the disconnect between current policy approaches, often focused narrowly on technological competition, and the material realities of AI development, which relies fundamentally on extractive economies that span multiple geographies. Only by attending to the full AI stack—including hardware, data, energy, and labor—can we grasp the true costs and consequences of AI systems. This work explores how the emergence of generative AI has intensified what analysts describe as a “critical mineral supercycle,” heightening geopolitical tensions—particularly between China and the United States—over access to essential resources including copper, cobalt, lithium, rare earth elements, as well as water, energy, and land. This global dependency often imposes disproportionate costs on local communities through land displacement, environmental degradation, labor exploitation, and resource depletion, while failing to acknowledge the indispensable contributions of Global South nations to the global technological ecosystem.

Workshop on "The Geopolitics of Critical Minerals and the AI Supply Chain"

The development and deployment of generative artificial intelligence is reshaping the geopolitical landscape and reconfiguring trade flows at a critical juncture in the global economy. Critical minerals essential for AI infrastructure have become focal points of resource nationalism, extractive capitalism, and political contestation. Despite this intensifying interconnectedness, policy frameworks and research on the AI technology stack often obscure its material underpinnings, privileging focus on the AI "short stack" compute, chips, databases, storage spaces, and clouds that enable AI models and systems rather than the "full stack" which includes a range of human and natural resources. This thematic siloing has resulted in a gap between scholars studying AI systems and other emerging technologies and those studying critical minerals and natural resource ecosystems, despite the fact that these domains are tightly linked and even path dependent through geopolitical dynamics.

Building on research initiated by Alondra Nelson, Tatiana Carayannis, and Marie-Therese Png, this workshop sought to address this gap. The ST&SV Lab convened a multisector, multidisciplinary group of scholars working across AI research and critical minerals supply chain research to open new lines of inquiry into the entangled material, political, and epistemic infrastructures underpinning AI. The aims of this workshop were to support the development of new theories and frameworks accounting for the full breadth of the AI value chain, to build a community of research and practice at the intersection of AI and critical mineral supply chains, and to set the foundation for future research collaborations and policy recommendations. Read the workshop summary report here.

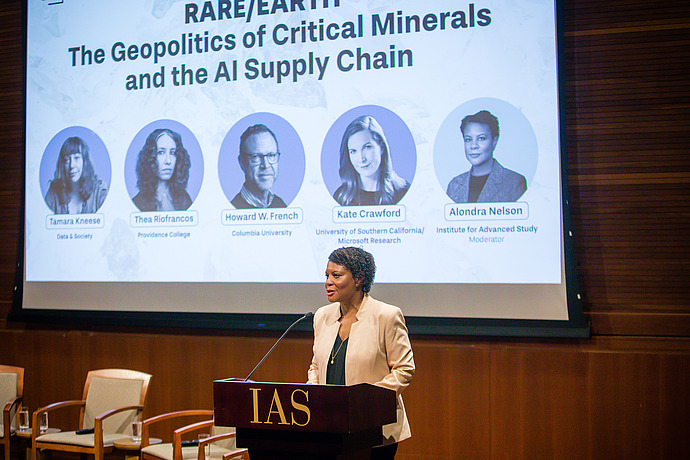

The workshop was preceded by a public panel titled: “RARE/EARTH: The Geopolitics of Critical Minerals and the AI Supply Chain,” which was introduced by Professor Nelson and held at the Institute for Advanced Study on Monday, June 2, 2025.

RARE/EARTH: The Geopolitics of Critical Minerals and the AI Supply Chain, A Panel Discussion

The hidden architecture behind an artificial intelligence “stack” extends from cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia to data centers in Chile and the United States, and from natural resources to local communities. A Science, Technology, and Social Values Lab panel at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton discussed the geopolitical implications of the growing demand for critical minerals to fuel the expansion of the AI ecosystem.

- Nations that once seemed peripheral to cutting-edge technological advancement now sit atop the raw materials that make Silicon Valley possible

- Material dependencies in AI supply chains are also human ones, ranging from mines across the Global South to data workers worldwide engaged in invisible cognitive labor

- A pathway to more equitable, sustainable management of critical minerals for AI can only be mapped by attending to the AI stack’s full, hidden architecture

Technologists commonly describe the architecture of artificial intelligence (AI) as a three-tiered “stack,” with semiconductors at the foundation, data centers in the middle, and applications at the surface. Yet the full, hidden architecture of the AI stack extends from cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo to the lithium extraction sites of Chile. In addition to multiple critical minerals, this architecture also includes energy and water resources for AI power networks, circuit boards, and cooling systems.

In June 2025, the Science, Technology and Social Values Lab hosted a panel discussion at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) to consider the intersections of AI, critical minerals, and the geopolitics that connect mining and other resource extraction, and labor. An audience that included several international experts with direct experience of these dynamics in their own countries, regions, and research topics provided further insights into a subject that is poorly understood yet fraught with urgent, geopolitical implications.

“Nations that once seemed peripheral to cutting-edge technological advancement, many in the Global South, now find themselves at the center of new forms of power,” observed Alondra Nelson, the Harold F. Linder Professor at the IAS, in her opening remarks. “This is not because they have suddenly developed Silicon Valley-style innovation hubs, but because they sit atop the raw materials that make Silicon Valley possible.”

A Convening of Expert Voices to Reimagine Global AI Governance

In the 90-minute conversation, the panelists covered a wide-range of geopolitical issues raised by AI supply chains that many of us never see or consider—from the legacy of colonialism in the Global South to the environmental impact of data centers in the United States. The discussion began with each of the panelists explaining how their research sheds light on different aspects of AI’s hidden architecture.

Dr. Tamara Kneese, director of the Climate, Technology, and Justice program at the Data & Society Research Institute in New York City, described how her work on “data extractivism” and generative AI’s abuse of labor connects with past histories of injustice.

Picking up on this theme, Howard W. French, professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and Foreign Policy columnist, recalled how his experience as a foreign correspondent in mineral-rich African countries first alerted him to the links between violence and the same aggressive resource extraction that now services the AI industry.

Thea Riofrancos, a professor of political science at Providence College and author of Extraction: The Frontiers of Green Capitalism, explained how her fieldwork in Chile’s Atacama Desert, host to massive lithium mines, provided a graphic case study of the social and environmental damage caused by supplying this critical mineral for the AI stack.

Professor Kate Crawford, a leading scholar of AI and its material impacts at the University of Southern California, and author of Atlas of AI, said that she first became aware that AI was an extractive, wasteful industry a decade ago, when she and colleagues mapped the life cycle of an Amazon Echo, from assembly to eventual disposal, often in developing countries.

These contrasting perspectives informed a debate which highlighted several themes requiring urgent attention by the AI industry and governments worldwide to ensure a healthy global AI ecosystem.

Material Dependencies Have Human Consequences

A recurring theme throughout the discussion was the need to recognize that the AI industry’s dependence on critical minerals also creates human dependencies. Every technological AI stack is also a social stack, extending far beyond the boundaries that engineers typically draw. For instance, it encompasses an army of data workers, many based in Africa and Asia, who perform invisible cognitive labor, such as cleaning the datasets that enable machine learning.

Meanwhile, the AI stack—considered in its entirety—can have devastating consequences on local populations. Thea Riofrancos vividly illustrated this point from her fieldwork in Chile’s Atacama Desert, the second-driest place on Earth, which supplies around 20 percent of the world’s lithium, a critical mineral for AI technologies. Yet even this arid region is home to 18 indigenous communities whose lives have been severely affected by the environmental damage caused by vast lithium mining operations. “When you go to the beginning of the supply chain, a lot comes undone about how we think about what counts as technology and what we think an extractive frontier means,” Prof. Riofrancos said.

AI Infrastructure Demands Are Causing Immense Environmental Harm

The panel considered how countries are constantly shifting their definition of what they deem to be critical minerals, as the global competition intensifies for resources such as lithium, gallium, and cobalt, which are essential for AI stacks and many other applications. Prof. Nelson highlighted how the United Nations High-level Advisory Board on AI’s Governing AI for Humanity report (September 2024), to which she contributed, calling for enhanced international cooperation on AI arrived at a moment when the declining influence of the UN, the World Trade Organization, and other multilateral bodies makes such collaboration increasingly difficult to achieve.

In this context, Kate Crawford drew attention to the common misconception that AI is somehow an “invisible” industry whose concrete impact on the planet is minimal. She observed from her research for Atlas of AI that the reverse is true, with the advent of generative AI triggering a “staggering” acceleration in the sector’s consumption of critical minerals, energy, and water resources, amid inadequate or non-existent national and international regulation. Prof. Crawford noted that globally, generative AI tools and systems are “currently using as much energy as the nation of Japan,” while on an individual level, a typical exchange with ChatGPT “is about the equivalent of pouring half a liter of water onto the ground” as waste in terms of the quantity required to enable the interaction.

A Future Worth “Winning”

Against this challenging geopolitical backdrop, Tamara Kneese emphasized the need to also consider the impact of AI on the international labor market. “The idea that we can now replace labor altogether with AI is a fantasy that the industry is of course willing to run with in order to save money,” she said. Dr Kneese pointed out that within the AI industry, even senior developers at large tech companies are starting to feel that their jobs are under threat, as they are increasingly asked to do coding work with help from software such as Copilot, rather than hire junior assistants.

Howard W. French, whose books include Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, warned about the risk of reproducing colonial patterns of extraction in the service of technological development. He cited the odious example of the Portuguese slave trade in Angola, where the colonial power assumed the supply of human beings was limitless. Prof. French noted that the Portuguese saw the pillaging of Angola’s human and natural resources as supporting Brazil’s development, a zero-sum game with relevance to today’s rampant extraction of critical minerals for AI and other tech industries. “Is there enough to last us until the end of time, or to the end of our computing desires?” Prof. French asked. “Somehow, I doubt it.”

Such observations, echoed by other panel members, naturally raised the question at the end of the discussion about whether a global AI race is worth “winning” at all, given the environmental and human impacts.

Four Calls to Action

Prof. Nelson concluded the panel by asking the panelists for their views about how the trajectory of AI development can be redirected to serve communities rather than just corporations. Dr. Kneese advocated greater efforts to support collective labor action across the global AI supply chain, linking workers from mines in the Global South to data centers in the developed world around their common interests. Prof. Riofrancos called for increased “South-South coordination” between countries rich in critical AI minerals to defend their resources from damaging exploitation by more powerful states. Prof. French stressed the need for the Global North to overcome diplomatic obstacles and enlist China as a partner in building a better international framework for mineral extraction. Lastly, Prof. Crawford found cause for optimism in the beginnings of public resistance in the US to AI developments which harm the local community.

More broadly, the panelists agreed that only by attending to the full AI stack, including its hidden architecture, can a pathway be mapped that leads to more equitable, sustainable management of the critical minerals on which the industry depends.

The panel was the kickoff discussion for a research workshop at the IAS to follow on “The Geopolitics of Critical Minerals and the AI Supply Chain.”

Read Professor Nelson’s opening remarks, watch the full discussion here, and join our mailing list to follow the work of the Science, Technology, and Social Values Lab.