Piet Hut

Field of study

Website

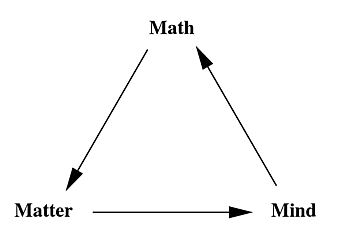

In 2024, Piet Hut started to lay the foundations of a new research program, referred to as FEST (Fully Empirical Science and Technology). It explores the working hypothesis that a rigorous science of mind can be developed on a par with the natural sciences, using the mind itself as a laboratory for disciplined, empirical investigation. The program rejects both the assumption that science can only study matter and the reduction of mind to matter, while remaining hypothesis-driven, subject to intersubjective scrutiny, and governed by a self-organizing peer community. Its aim is not to replace existing sciences, but to explore whether a mature science of mind might eventually connect coherently with natural science, without presupposing what form such a connection would take.

At the heart of this research program lies a simple but demanding methodological move: to treat the mind not merely as an object of study, but as an instrument of investigation. Just as natural science relies on carefully designed experiments carried out in physical laboratories, a science of mind must rely on direct, repeatable experiments carried out within experience itself. The first step, therefore, is to use the mind as a natural laboratory for disciplined inquiry, subject to intersubjective scrutiny and replication, as has always been the case in natural science. This does not mean privileging private experience as unquestionable data; rather, it requires developing shared methods, vocabularies, and standards that allow experiential observations to be compared, tested, and refined collectively.

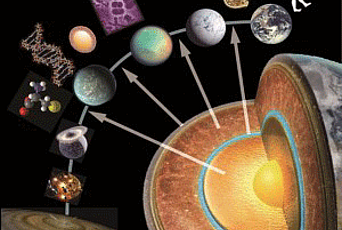

Historical precedents suggest that such an approach is not as radical as it may first appear. The emergence of modern physics depended in essential ways on millennia of accumulated systematic observations, long before stable theoretical frameworks were in place. Theory did not lead observation; it crystallized from it. For a science of mind modeled on natural science, the most conservative approach would be to similarly start with a sufficiently rich and carefully curated body of empirical observations. Where the Babylonians and the Greeks provided observations and theories, extensive records preserved in contemplative traditions across cultures can act as an equally valuable empirical resource for deep studies of the mind, encompassing both disciplined practices and prescientific theories.

A central obstacle to the development of a science of mind has not been the absence of observations, but the absence of an appropriate institutional framework. What has been missing is a self-governing peer community, independent of religious institutions and resistant to schisms. Contemplative lineages have preserved invaluable experiential knowledge. In certain cultures and periods, their social structures have allowed both transmission and innovation, which can still be drawn upon. However, in many—if not most—cases, contemplatives had limited autonomy, being subject to political power structures, in contrast to natural science, which has so far experienced only short-lived regional interventions.

These historical constraints point directly to the design requirements for a viable science of mind today. What is needed is not the wholesale adoption of existing contemplative traditions, but a careful distillation of practices, observations, and provisional theories that can be examined and refined within an open, self-governing framework. Such a framework must support methodological transparency, encourage critical comparison across traditions and cultures, and protect the autonomy of inquiry from religious, political, or ideological authority. In this sense, the development of a science of mind calls not only for new methods, but for institutional forms that allow those methods to evolve collectively and without schisms.

Such an institutional framework cannot be established all at once. Like natural science itself, it would have to emerge gradually, through shared practices and inquiry rather than prescribed beliefs, and across cultural and disciplinary boundaries. For this reason, the present effort is conceived as a pilot program: an exploratory attempt to see whether a self-governing community of inquiry can grow to nurture a science of mind, and whether it can sustain critical rigor without fragmenting into competing schools or reverting to authority-based structures. Participation is therefore open in principle to people from all walks of life, provided they are willing to engage with the discipline and care that empirical inquiry requires.

The long-term vision of this research program is deliberately ambitious, yet carefully constrained. It explores the possibility that an independent science of mind could eventually become mutually informative with natural science, the current science of matter, in the way that previously separate domains of inquiry have at times converged. Whether such a connection can be achieved, and what form it might take, remains an open question rather than a guiding assumption. To keep this exploratory character visible, the work has been developed in a transparent, process-oriented manner, preserving intermediate steps, revisions, and unresolved questions alongside provisional results. In this way, the program aims not to present a finished system, but to document an ongoing experiment.