Morals and Moralities: A Critical Perspective from the Social Sciences

Philosophers have always been interested in moral questions, but social scientists have generally been more reluctant to discuss morals and moralities. This is indeed a paradox since the questioning of the moral dimension of human life and social action was consubstantial to the founding of their disciplines.

A clue to this paradox resides in the tension between the descriptive and prescriptive vocations of social sciences: is the expected result of a study of moralities a better understanding of social life, or is the ultimate goal of a science of morals the betterment of society? At the beginning of the twentieth century, the German sociologist Max Weber, following the first line, pleaded for a value-free study of value-judgment, examining, for instance, the role played by the Protestant ethic in the emerging spirit of capitalism. His French contemporary Emile Durkheim, more sensitive to the second option, strongly believed that research on morality would not be worth the labor it necessitates were scientists to remain resigned spectators of moral reality, a position that did not prevent him from proposing a rigorous explanation of why we obey collective rules. This dialectic between exploring norms and promoting them, between analyzing what is considered to be good and asserting what is good, has thus been at the heart of the social sciences ever since their birth.

For anthropology, the problem was even more crucial, since the confrontation with other cultures, and therefore other moralities, led to an endless discussion between universalism and relativism. Given the variety of norms and values across the globe and their transformation over time, should one affirm that some are superior or accept that they are all merely incommensurable? Most anthropologists, from the American father of culturalism, Franz Boas, to the French founder of structuralism, Claude Lévi-Strauss, adopted the second approach, certainly reinforced by the discovery of the historical catastrophes engendered by ideologies based on human hierarchy, whether they served to justify extermination in the case of Nazism, exploitation for colonialism, or segregation with apartheid. This debate was recently reopened with issues such as female circumcision (renamed genital mutilation) and traditional matrimonial strategies (requalified as forced marriages), with many feminists arguing in favor of morally engaged research when it came to practices they viewed as unacceptable.

Considering these difficulties, scientific but also political and ethical, it is all the more remarkable that the social sciences have reinvested in the field of morals and moralities during the past decade. This evolution reflects a broader trend in contemporary societies where moral issues have become central in the public sphere, to the point that most domains of activity have become concerned with moral evaluations and justifications. Human rights have entered the space of international relations, military operations have been presented as humanitarian wars, bioethics has redefined the boundaries of medical research, greed in finance has been denounced as unethical, compassion has become a political virtue, poverty has been assessed according to merit. Under these changing circumstances, the growing public presence of moral questions could no longer be ignored by the social scientists, whose expertise was even on occasion solicited.

Here, it is important to understand the profound theoretical and methodological difference between social sciences and philosophy, but also increasingly the evolutionary and cognitive sciences in their respective approaches to moral problems. Philosophers, biologists, and psychologists proceed by reduction—typically to pure moral dilemmas, generally leading to simple alternatives that do not reflect reality but formalize it in order to produce conceptualization. In this vein, evolutionary and cognitive scientists recently have proposed a universal moral grammar, which can be seen as the elementary forms of moral judgments and moral sentiments. By contrast, sociologists, anthropologists, and historians deal with complex and impure situations—because this is the reality of human life and social action. The lines between moral issues and political, economic, religious, legal, aesthetic, and social questions are often blurred. Social scientists know through their observations that there is no universal morality. Even murder can be condemned or praised, according to cultural environments, historical moments, and specific contexts.

It is to apprehend this complexity and impurity of morals and moralities in contemporary societies that the program “Towards a Critical Moral Anthropology,” funded by the European Research Council, was conceived. This collaborative project brings together a group of twelve sociologists, anthropologists, and political scientists. It is being developed on both sides of the Atlantic: in Paris, at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, and in Princeton, at the Institute for Advanced Study, taking advantage of the presence of members simultaneously exploring similar questions through different objects. It has both a theoretical and an empirical dimension. On the one hand, it proposes a critical inquiry into the new field of the anthropology of morals and moralities, relating moral issues to their historical formation and political background. On the other hand, it includes a study of the way immigrants and minorities are treated by institutions such as the police, justice, prison, social work, and the mental health system in France, articulating the moral economy of these issues at the national level and the moral work of the social agents in their respective institutions.

Indeed, immigrants and minorities represent, in many societies, the most marginalized, stigmatized, and discriminated against. The institutions with which they deal are in part repressive (police, justice, prison) and in part rehabilitative (social work, mental health). In both cases, the technical matter of each profession (law, surveillance, assistance, psychiatry) does not entirely account for the decisions made or attitudes adopted toward the public: a moral evaluation is always involved—implicitly or explicitly. Police officers, magistrates, and guards, as well as social workers and health professionals, use moral categories to disqualify or absolve, construct moral communities to exclude or include, develop moral justifications to mistreat or respect. Of course, these moral elaborations are not born from a social void. Actually, the scientific challenge is to understand how public discourses and public policies influence institutional and professional practices—and are, in turn, consolidated or sometimes reformulated through the latter. In other words, we seek to understand how the macrosocial (politics and policies) and the microsocial (beliefs and practices) are articulated—which is one of the major theoretical interrogations, if not enigmas, for social scientists.

Consider, for instance, the administrative and judicial process through which the applications of asylum seekers are assessed to determine whether or not they will be granted refugee status. In Europe, public discourse regarding so-called “bogus refugees” has progressively infiltrated the everyday work of the officers and magistrates in charge of the evaluation of the applicants. Whereas trust was common three decades ago, when nine asylum seekers out of ten were granted the precious status, suspicion has become the rule, leading to increasingly lower rates of recognition, currently down to two out of ten. In this new context, where the veracity of their accounts is very difficult to establish, the sincerity of the applicants is to a greater extent assessed through sympathy produced in reaction to their display of emotions. Paradoxically, however, the more severe the judgments are, the more convinced the judges are of their fairness. For them, the loss of credit of the asylum seekers’ word has for corollary the increasing worth of asylum as an abstract principle—to the point of rendering it inaccessible. Ultimately, policy makers see their doubts concerning the veracity of accounts and the sincerity of the applicants confirmed by the low rates of recognition. Norms and values therefore circulate between the macrosocial and the microsocial, between national forums, where immigration issues are debated, and local bureaucracies, where vital decisions are made. The moral economy of asylum is thus deeply embedded in political issues and dependent on social questions.

To apprehend such interlinked scales and intertwined domains, the method of choice is ethnography, that is, the participant observation, over lengthy periods of time, of the activity of the professionals in their respective institutions: the police in the streets, the magistrates in the courts, the guards in the prisons, social workers in their administration, psychiatrists in their hospital. This means a reorientation of traditional fieldwork. Anthropologists have long studied distant and isolated ethnic groups. They have discovered that their place is also at home, where certain social worlds are perhaps no less exotic or no less misrepresented than what they used to call “primitive societies.” In particular, the inquiry into morals and moralities offers the possibility to seize simultaneously the shared norms and values across social worlds and the specific rules and sensibilities that singularize each of them—a felicitous addition to what Clifford Geertz, founding Professor of the Institute’s School of Social Science, regarded as the “ethical dimension of anthropological fieldwork.”

Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present

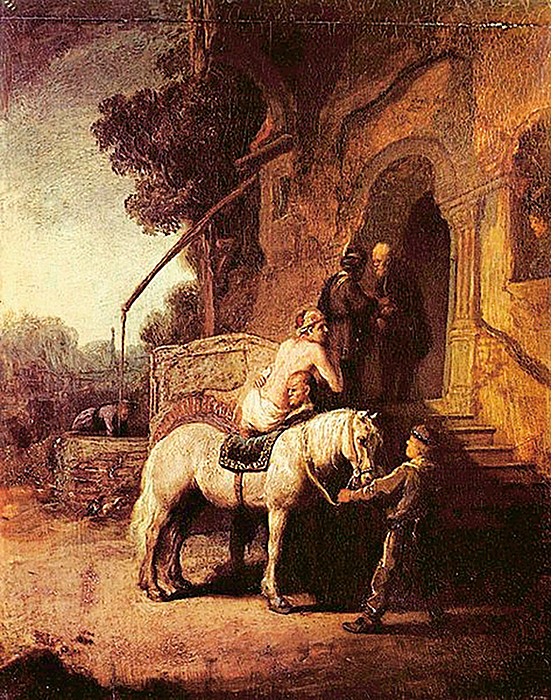

In the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia, Clifford Geertz commented with melancholy . . . that “fatality on such a scale, the destruction not only of individual lives but of whole populations of them, threatens the conviction that perhaps most reconciles many of us, insofar as anything this-worldly does, to our own mortality: that, though we ourselves may perish, the community into which we were born, and the sort of lives it supports, will somehow live on.” One could extend this profound insight by suggesting that the significance of such a fatality is not only about our mourning of a possibly lost world, of which all traces may even disappear; it is also about our sense of belonging to a wider moral community, whose existence is manifested through the compassion toward the victims. For the attentive observer of the tsunami, the impressive magnitude of the toll, with its tens of thousands of casualties, was as meaningful as the unparalleled deployment of solidarity, with its billions of dollars of aid. We lamented their dead but celebrated our generosity. The power of this event resides in the rare combination of the tragedy of ruination and the pathos of assistance. . . . The moral landscape thus outlined can be called humanitarianism. Although it is generally taken for granted as a mere expansion of a supposed natural humaneness that would be innately associated with our being human, humanitarianism is a relatively recent invention, which raises complex ethical and political issues. . . .

The year 2010 began with the dreadful earthquake in Haiti, which precipitated a remarkable mobilization worldwide, particularly from France and the United States. We witnessed in fact a competition between the two countries, whose governments and populations rivaled each other in solicitude toward the victims, bounteously sending troops, physicians, goods, and money, while raising the suspicion of the pursuit of goals other than pure benevolence toward a nation that was successively oppressed by the former and exploited by the latter. This emulation was certainly triggered by goodwill, and one should not minimize the altruistic engagement and charitable efforts of individuals, organizations, churches, and even governments involved in the treatment of the injured and later in the reconstruction efforts. Yet one cannot avoid thinking how rewarding was this generosity. For a fleeting moment we had the illusion that we shared a common human condition. We could forget that only 6 percent of Haitian asylum seekers are granted the status of refugee in France, representing one of the lowest national rates, far behind those coming from apparently peaceful countries, or that thirty thousand Haitians were on the deportation lists of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency. The cataclysm seemed to erase the memories of the French and subsequent American exploitation of the island. Our response to it signified the promise of reparation and the hope for reconciliation.

In contemporary societies, where inequalities have reached an unprecedented level, humanitarianism elicits the fantasy of a global moral community that may still be viable and the expectation that solidarity may have redeeming powers. This secular imaginary of communion and redemption implies a sudden awareness of the fundamentally unequal human condition and an ethical necessity to not remain passive about it in the name of solidarity—however ephemeral this awareness is, and whatever limited impact this necessity has. Humanitarianism has this remarkable capacity: it fugaciously and illusorily bridges the contradictions of our world, and makes the intolerableness of its injustices somewhat bearable. Hence, its consensual force.— Didier Fassin in Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present (University of California Press, 2011)

Detailed information on this research can be found on the website http://morals.ias.edu/, including corresponding publications, seminar programs, and related bibliographies.